Tres horas entre dos aviones

Traducción del inglés por Constanza Eugenia Trujillo Amaya

Texto original de F. Scott Fitzgerald

Edición por Maritza García

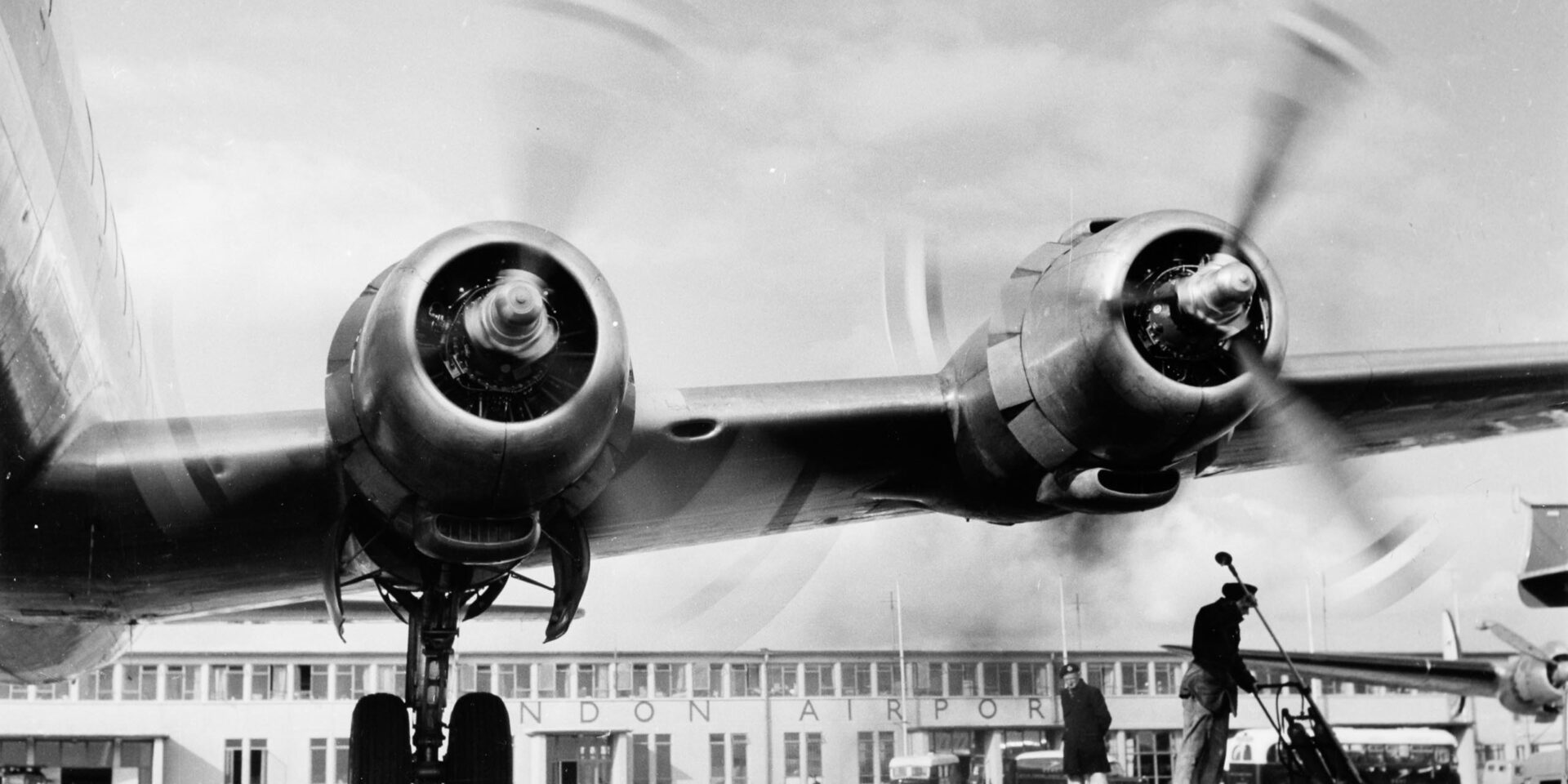

Fotografía: «An Aircraft is due to taxi out from London Heathrow Airport» de SAS Scandinavian Airlines

Era una idea descabellada, pero Donald estaba de humor, saludable y aburrido, con la sensación de haber cumplido con un tedioso deber. Ahora, quería su recompensa. Quizás.

Cuando el avión aterrizó, salió a una noche de verano del Medio Oeste y se dirigió al apartado aeropuerto del pueblo, conocido como una vieja y roja ‘estación de tren’. No sabía si estaba viva, ni si vivía en ese pueblo, ni cuál era su actual apellido. Con una creciente emoción, buscó en el directorio telefónico a su padre, que a lo mejor también habría muerto, en algún lugar, en esos veinte años.

Núm. Judge Harmon Holmes, Hillside 3194.

Una jovial voz femenina contestó cuando preguntó por la señorita Nancy Holmes.

—Nancy es ahora la señora (Walter) Gifford. ¿Quién habla?

Sin embargo, Donald colgó sin responder. Había descubierto lo que quería saber y solo tenía tres horas. No recordaba a ningún Walter Gifford, y hubo otro momento de suspenso mientras hojeaba el directorio telefónico. Podría haberse casado fuera del pueblo.

Núm. Walter Gifford, Hillside 1191. La sangre le volvió a la yema de los dedos.

—¿Aló?

—Aló. ¿Está la señora Gifford? Soy un viejo amigo de ella.

—Soy la señora Gifford.

Recordaba, o creyó recordar, la graciosa magia de su voz.

—Soy Donald Plant. No nos hemos visto desde que yo tenía doce años.

—¡Oh, oh, oh! —El tono era de total sorpresa, muy amable, pero no logró distinguir ni alegría ni alguna evidencia de que lo hubiera reconocido.

—¡Donald! —añadió la voz. Esta vez había algo más en su tono que una memoria en dificultad.

—¿Cuándo regresaste al pueblo? —Enseguida, de manera cordial— ¿Dónde estás?

—Estoy en las afueras del aeropuerto, solo por unas pocas horas.

—Bueno, ven a verme.

—¿Seguro que no estás a punto de acostarte?

—¡Cielos no! —exclamó—. Estaba aquí sentada tomando sola un whisky con soda. Solo dile al taxista…

Donald analizó la conversación durante el camino. Sus palabras ‘en el aeropuerto’ daban a entender que él había conservado su lugar en la alta burguesía. La soledad de Nancy podría indicar que se había convertido en una mujer poco atractiva, sin amistades. Su esposo podría estar lejos o en la cama. Y como ella siempre tendría diez años en sus sueños, lo del vaso de whisky con soda lo había impactado. Se acomodó con una sonrisa, estaría muy cerca de los treinta.

Al final de una calle curva, vio a una belleza menuda, de cabello oscuro parada contra la puerta iluminada, con un vaso en la mano. Sorprendido con su indiscutible materialización, Donald salió del taxi diciendo:

—¿Señora Gifford?

Ella encendió la luz del pórtico y se le quedo mirando, con ojos muy abiertos y dudosa. De la perpleja expresión emergió una sonrisa.

—Donald, eres tú, todos cambiamos tanto. ¡Oh, esto es extraordinario!

Mientras entraban, sus voces resonaron al decir ‘todos estos años’, y Donald sintió un nudo en el estómago. Esto sobrevino, en parte, por la visión de su último encuentro, cuando ella se le atravesó en bicicleta amenazadora; y en parte, por temor a que no tuvieran nada que decirse. Era como una reunión de la facultad, pero en ese momento la incapacidad de reanudar con el pasado quedó disimulada por la precipitada y bochornosa situación. Horrorizado, se dio cuenta de que el encuentro podría convertirse en una hora interminable y sin sentido. Se desmoronó angustiado.

—Siempre fuiste una persona encantadora; pero estoy un poco impactado de ver lo hermosa que eres.

Funcionó. El reconocimiento inmediato de haber cambiado de condición, el cumplido audaz, los convirtió en interesantes extraños en lugar de torpes amigos de la infancia.

—¿(Quieres) un whisky con soda? —preguntó—. ¿No? Por favor no pienses que me he convertido en una bebedora secreta, es que esta era una noche gris. Esperaba a mi esposo, pero me telegrafió diciendo que se tardaría dos días más. Él es muy amable, Donald, y muy atractivo. Como de tu aspecto y color de piel —vaciló—. Creo que está interesado en alguien en Nueva York, y no sé.

—Después de haberte visto, suena inconcebible—le aseguró—. Estuve casado durante seis años y en aquel entonces me torturé de tal manera. Luego, un día, arranqué los celos de mi vida para siempre. Después de la muerte de mi esposa, me alegré mucho de ello. Eso me dejó un vivo recuerdo, nada malo ni feo ni algo difícil en que pensar.

Ella lo miró con cuidado, luego con simpatía, mientras él hablaba.

—Lo siento mucho —dijo ella—. Y después de un momento prudencial—, has cambiado mucho. Voltea la cabeza. Recuerdo que mi padre decía, «ese muchacho tiene cerebro».

—A lo mejor alegaste lo contrario.

—Estaba asombrada. Hasta entonces había pensado que todo el mundo tenía un cerebro. Por eso se me quedó grabado en la cabeza.

—¿Qué otra cosa se te quedó grabada? —preguntó sonriendo.

De repente, Nancy se levantó y se alejó unos pasos deprisa.

—Ah, ya —le reprochó ella —. ¡Eso no se vale! Supongo que era una niña traviesa.

—No lo eras —dijo él con firmeza—. Y ahora quisiera una copa.

Mientras ella le servía, aún con el rostro apartado, él continuó:

—¿Crees que fuiste la única niña a la que alguna vez besaron?

—¿Te gusta el tema? —preguntó ella. Su irritación momentánea se disipó y dijo— ¡Santo cielo! Nos divertimos. Como en la canción.

—En el paseo en trineo.

—Sí, y el picnic en casa de alguien, ella de Trudy James. Y en Frontenac ese… esos veranos.

Lo que más recordaba era el paseo en trineo y el beso en sus frías mejillas, en un rincón en la paja, mientras ella se reía de las frías y blancas estrellas. La pareja de al lado estaba de espaldas, y él le beso el pequeño cuello y las orejas, pero no los labios.

—Y la fiesta de los Macks, cuando jugaron a la oficina de correos y yo no pude ir porque tenía paperas —dijo—.

—No recuerdo eso.

—¡Oh, tú estabas allí! Te besaron y yo estaba loco de celos, como nunca lo he estado desde entonces.

—Qué curioso, no lo recuerdo. A lo mejor quería olvidarlo.

—¿Pero, por qué? —preguntó divertido—. Éramos dos niños bastante inocentes. Nancy, cuando alguna vez hablé con mi esposa del pasado, le dije que tú eras la chica que había querido casi tanto como a ella. Sin embargo, creo, de verdad, que te quise mucho más. Cuando nos mudamos a las afueras del pueblo te lleve (conmigo), como una bala de cañón en las mis entrañas.

—¿Eras ése tan provocador?

—¡Por Dios, sí! Yo… —de repente, él se dio cuenta de que estaban a solo sesenta centímetros el uno del otro, que le estaba hablando como si la amara en ese instante, que ella lo estaba mirando con los labios entreabiertos y los ojos nublados.

—Continúa —dijo ella—, me da vergüenza decir que eso me gusta. No supe entonces que te hubieras sentido tan decepcionado. Pensé que era yo la decepcionada.

—¡Tú! —exclamó él—. No te acuerdas de haberme mandado a pasear en la tienda —se rio—. Me sacaste la lengua.

—No recuerdo nada. Me pareció que fuiste tú quien me mandaste a pasear —le puso la mano con suavidad sobre el brazo, casi (como) consolándolo—. Tengo un álbum de fotos arriba que no he mirado en años. Lo sacaré.

Durante cinco minutos, Donald se quedó pensando en dos cosas. La primera, la incapacidad de conciliar lo que diferentes personas recuerdan sobre un mismo evento; y la segunda que, como mujer, Nancy lo atraía de manera aterradora, tanto como cuando era niña. En media hora había aparecido una emoción que no había conocido desde la muerte de su esposa y que nunca esperóo volver a sentir.

Uno al lado del otro, en el sofá, abrieron el álbum entre los dos. Nancy lo miró sonriendo y muy contenta.

—Oh, esto es muy divertido —dijo ella—. Es muy divertido que seas tan amable, que me recuerdes tan hermosa. Déjame decirte, ¡ojalá lo hubiera sabido entonces! Después de que te fuiste te odié.

—Qué lástima —dijo él con cautela.

—Pero ahora no —le aseguró ella, y luego de manera impulsiva—, bésame y hagamos las paces. Eso no es ser una buena esposa —dijo después de un minuto—. De verdad, no recuerdo haber besado a dos hombres desde que me casé.

Estaba emocionado, pero más que todo confundido. ¿Había besado a Nancy? ¿o a un recuerdo? ¿o a esta adorable y temblorosa extraña que le apartó la mirada deprisa y volteó la página del álbum?

—¡Espera! —dijo él—. No creo que pueda ver otra foto durante unos instantes.

—No volveremos a hacerlo. No estoy muy tranquila.

Donald dijo una de esas cosas banales que dicen tanto.

—¿No sería terrible que nos volviéramos a enamorar?

—¡Basta! —rio ella, pero sin mucho aliento—. Todo se acabó. Fue un momento. Un momento que deberé olvidar.

—No se lo digas a tu esposo.

—¿Por qué no? Casi siempre le cuento todo.

—Lo puedes herir. Nunca le digas algo así a un hombre.

—Vale, no lo haré.

—Bésame otra vez —dijo él sin querer, pero Nancy había pasado una página y señalaba con ansiedad una foto.

—Aquí estás —gritó— ¡Preciso!

Miró. Era un pequeño niño en pantalones cortos, parado en un muelle con un velero al fondo.

—Recuerdo —rio victoriosa—, el mismo día en que la tomaron. Kitty la cogió y yo se la robé.

Durante un momento, Donald no logró reconocerse en la foto; entonces se acercó más y no pudo reconocerse en modo alguno.

—Ese no soy yo —dijo.

—Oh, sí. Fue en Frontenac, el verano en el que solíamos ir a la cueva.

—¿Qué cueva? Estuve solo tres días en Frontenac —de nuevo aguzó la vista hacia la imagen un tanto amarillenta—. Ese no soy yo. Es Donald Bowers. Nos parecíamos bastante.

En ese momento fue ella quien se le quedó mirando, se inclinó hacia atrás y pareció tomar distancia.

—¡Pero tú eres Donald Bowers! —exclamó; subió la voz—. No, no lo eres. Eres Donald Plant.

—Te lo dije por teléfono.

Estaba de pie, con una cara un tanto horrorizada.

—¡Plant! ¡Bowers! Debo estar loca. ¿o fue ese trago? Al comienzo estaba un poco confundida cuando te vi. ¡Mira! ¿Qué te he dicho?

Él intentó mantener una calma monacal mientras volteaba una página del álbum.

—Nada en absoluto —dijo. Imágenes donde él no estaba se formaban y volvían a formar ante sus ojos, Frontenac, una cueva, Donald Bowers— ¡Rompiste conmigo!

Nancy habló desde el otro lado de la habitación.

—No cuentes nunca esta historia —dijo—. Las historias tienen tal manera de dar vueltas.

No hay ninguna historia —vaciló; y pensó, «así que era una niña mala».

Ahora, de repente, se sintió invadido de unos celos furiosos y salvajes contra el pequeño Donald Bowers, él que había desterrado los celos para siempre de su vida. En los cinco pasos que dio a través de la habitación aplastó veinte años y la existencia de Walter Gifford de una zancada.

—Bésame otra vez, Nancy —dijo, arrodillándose junto a su silla y poniendo una mano sobre su hombro; pero Nancy se alejó.

—Dijiste que tenías que tomar un avión.

—No es nada. Puedo perderlo. No tiene importancia.

—Por favor, vete —dijo ella con voz indiferente—. Por favor, trata de imaginar cómo me siento.

¡Pero actúas como si no me recordaras —gritó—, como si no recordarás a Donald Plant!

Sí. Te recuerdo muy bien… Pero todo eso fue hace mucho tiempo —su voz volvió a endurecerse—. El número del taxi es Crestwood 8484.

Camino al aeropuerto Donald sacudió la cabeza de un lado al otro. Era de nuevo él mismo, pero no lograba digerir la experiencia. Solo cuando el avión rugió en el cielo oscuro y los pasajeros se convirtieron en una entidad diferente del mundo corporativo de abajo, trazó un paralelo con el hecho de su vuelo. Durante cinco minutos deslumbrantes había vivido como un loco en dos mundos a la vez. Había sido un niño de doce años y un hombre de treinta dos, indisolubles e imposibles de mezclar.

Donald también había perdido mucho durante esas horas entre dos aviones, pero como la segunda mitad de la vida es un largo proceso de deshacerse de las cosas, era probable que esa parte de la experiencia no importara.

It was a wild chance but Donald was in the mood, healthy and bored, with a sense of tiresome duty done. He was now rewarding himself. Maybe.

When the plane landed he stepped out into a mid-western summer night and headed for the isolated pueblo airport, conventionalized as an old red ‘railway depot’. He did not know whether she was alive, or living in this town, or what was her present name. With mounting excitement he looked through the phone book for her father who might be dead too, somewhere in these twenty years.

No. Judge Harmon Holmes–Hillside 3194.

A woman’s amused voice answered his inquiry for Miss Nancy Holmes.

‘Nancy is Mrs Walter Gifford now. Who is this?’

But Donald hung up without answering. He had found out what he wanted to know and had only three hours. He did not remember any Walter Gifford and there was another suspended moment while he scanned the phone book. She might have married out of town.

No. Walter Gifford–Hillside 1191. Blood flowed back into his fingertips.

‘Hello?’

‘Hello. Is Mrs Gifford there–this is an old friend of hers.’

‘This is Mrs Gifford.’

He remembered, or thought he remembered, the funny magic in the voice.

‘This is Donald Plant. I haven’t seen you since I was twelve years old.’

‘Oh-h-h!’ The note was utterly surprised, very polite, but he could distinguish in it neither joy nor certain recognition.

‘Donald!’ added the voice. This time there was something more in it than struggling memory.

‘. . . when did you come back to town?’ Then cordially, ‘Where are you?’

‘I’m out at the airport–for just a few hours.’

‘Well, come up and see me.’

‘Sure you’re not just going to bed?’

‘Heavens, no!’ she exclaimed. ‘I was sitting here–having a highball by myself. Just tell your taxi man . . .’

On his way Donald analysed the conversation. His words ‘at the airport’ established that he had retained his position in the upper bourgeoisie. Nancy’s aloneness might indicate that she had matured into an unattractive woman without friends. Her husband might be either away or in bed. And–because she was always ten years old in his dreams–the highball shocked him. But he adjusted himself with a smile–she was very close to thirty.

At the end of a curved drive he saw a dark-haired little beauty standing against the lighted door, a glass in her hand. Startled by her final materialization, Donald got out of the cab, saying:

‘Mrs Gifford?’

She turned on the porch light and stared at him, wide-eyed and tentative. A smile broke through the puzzled expression.

‘Donald–it is you–we all change so. Oh, this is remarkable!’

As they walked inside, their voices jingled the words ‘all these years’, and Donald felt a sinking in his stomach. This derived in part from a vision of their last meeting–when she rode past him on a bicycle, cutting him dead–and in part from fear lest they have nothing to say. It was like a college reunion–but there the failure to find the past was disguised by the hurried boisterous occasion. Aghast, he realized that this might be a long and empty hour. He plunged in desperately.

‘You always were a lovely person. But I’m a little shocked to find you as beautiful as you are.’

It worked. The immediate recognition of their changed state, the bold compliment, made them interesting strangers instead of fumbling childhood friends.

‘Have a highball?’ she asked. ‘No? Please don’t think I’ve become a secret drinker, but this was a blue night. I expected my husband but he wired he’d be two days longer. He’s very nice, Donald, and very attractive. Rather your type and colouring.’ She hesitated, ‘–and I think he’s interested in someone in New York–and I don’t know.’

‘After seeing you it sounds impossible,’ he assured her. ‘I was married for six years, and there was a time I tortured myself that way. Then one day I just put jealousy out of my life forever. After my wife died I was very glad of that. It left a very rich memory–nothing marred or spoiled or hard to think over.’

She looked at him attentively, then sympathetically as he spoke.

‘I’m very sorry,’ she said. And after a proper moment,’ You’ve changed a lot. Turn your head. I remember father saying, «That boy has a brain.»‘

‘You probably argued against it.’

‘I was impressed. Up to then I thought everybody had a brain. That’s why it sticks in my mind.’

‘What else sticks in your mind?’ he asked smiling.

Suddenly Nancy got up and walked quickly a little away.

‘Ah, now,’ she reproached him. ‘That isn’t fair! I suppose I was a naughty girl.’

‘You were not,’ he said stoutly. ‘And I will have a drink now.’

As she poured it, her face still turned from him, he continued:

‘Do you think you were the only little girl who was ever kissed?’

‘Do you like the subject?’ she demanded. Her momentary irritation melted and she said: ‘What the hell! We did have fun. Like in the song.’

‘On the sleigh ride.’

‘Yes–and somebody’s picnic–Trudy James’s. And at Frontenac that–those summers.’

It was the sleigh ride he remembered most and kissing her cool cheeks in the straw in one corner while she laughed up at the cold white stars. The couple next to them had their backs turned and he kissed her little neck and her ears and never her lips.

‘And the Macks’ party where they played post office and I couldn’t go because I had the mumps,’ he said.

‘I don’t remember that.’

‘Oh, you were there. And you were kissed and I was crazy with jealousy like I never have been since.’

‘Funny I don’t remember. Maybe I wanted to forget.’

‘But why?’ he asked in amusement. ‘We were two perfectly innocent kids. Nancy, whenever I talked to my wife about the past, I told her you were the girl I loved almost as much as I loved her. But I think I really loved you just as much. When we moved out of town I carried you like a cannon ball in my insides.’

‘Were you that much–stirred up?’

‘My God, yes! I–‘ He suddenly realized that they were standing just two feet from each other, that he was talking as if he loved her in the present, that she was looking up at him with her lips half-parted and a clouded look in her eyes.

‘Go on,’ she said, ‘I’m ashamed to say–I like it. I didn’t know you were so upset then. I thought it was me who was upset.’

‘You!’ he exclaimed. ‘Don’t you remember throwing me over at the drugstore.’ He laughed. ‘You stuck out your tongue at me.’

‘I don’t remember at all. It seemed to me you did the throwing over.’ Her hand fell lightly, almost consolingly on his arm. ‘I’ve got a photograph book upstairs I haven’t looked at for years. I’ll dig it out.’

Donald sat for five minutes with two thoughts–first the hopeless impossibility of reconciling what different people remembered about the same event–and secondly that in a frightening way Nancy moved him as a woman as she had moved him as a child. Half an hour had developed an emotion that he had not known since the death of his wife–that he had never hoped to know again.

Side by side on a couch they opened the book between them. Nancy looked at him, smiling and very happy.

‘Oh, this is such fun,’ she said. ‘Such fun that you’re so nice, that you remember me so–beautifully. Let me tell you–I wish I’d known it then! After you’d gone I hated you.’

‘What a pity,’ he said gently.

‘But not now,’ she reassured him, and then impulsively, ‘Kiss and make up–. . . that isn’t being a good wife,’ she said after a minute. ‘I really don’t think I’ve kissed two men since I was married.’

He was excited–but most of all confused. Had he kissed Nancy? or a memory? or this lovely trembly stranger who looked away from him quickly and turned a page of the book?

‘Wait!’ he said. ‘I don’t think I could see a picture for a few seconds.’

‘We won’t do it again. I don’t feel so very calm myself.’

Donald said one of those trivial things that cover so much ground.

‘Wouldn’t it be awful if we fell in love again?’

‘Stop it!’ She laughed, but very breathlessly. ‘It’s all over. It was a moment. A moment I’ll have to forget.’

‘Don’t tell your husband.’

‘Why not? Usually I tell him everything.’

‘It’ll hurt him. Don’t ever tell a man such things.’

‘All right I won’t.’

‘Kiss me once more,’ he said inconsistently, but Nancy had turned a page and was pointing eagerly at a picture.

‘Here’s you,’ she cried. ‘Right away!’

He looked. It was a little boy in shorts standing on a pier with a sailboat in the background.

‘I remember–‘ she laughed triumphantly, ‘–the very day it was taken. Kitty took it and I stole it from her.’

For a moment Donald failed to recognize himself in the photo–then, bending closer–he failed utterly to recognize himself.

‘That’s not me,’ he said.

‘Oh yes. It was at Frontenac–the summer we–we used to go to the cave.’

‘What cave? I was only three days in Frontenac.’ Again he —strained his eyes at the slightly yellowed picture. ‘And that isn’t me. That’s Donald Bowers. We did look rather alike.’

Now she was staring at him–leaning back, seeming to lift away from him.

‘But you’re Donald Bowers!’ she exclaimed; her voice rose a little. ‘No, you’re not. You’re Donald Plant.’

‘I told you on the phone.’

She was on her feet–her face faintly horrified.

‘Plant! Bowers! I must be crazy. Or it was that drink? I was mixed up a little when I first saw you. Look here! What have I told you?’

He tried for a monkish calm as he turned a page of the book.

‘Nothing at all,’ he said. Pictures that did not include him formed and re-formed before his eyes–Frontenac–a cave–Donald Bowers–‘You threw me over!’

Nancy spoke from the other side of the room.

‘You’ll never tell this story,’ she said. ‘Stories have a way of getting around.’

‘There isn’t any story,’ he hesitated. But he thought: So she was a bad little girl.

And now suddenly he was filled with wild raging jealousy of little Donald Bowers–he who had banished jealousy from his life forever. In the five steps he took across the room he crushed out twenty years and the existence of Walter Gifford with his stride.

‘Kiss me again, Nancy,’ he said, sinking to one knee beside her chair, putting his hand upon her shoulder. But Nancy strained away.

‘You said you had to catch a plane.’

‘It’s nothing. I can miss it. It’s of no importance.’

‘Please go,’ she said in a cool voice. ‘And please try to imagine how I feel.’

‘But you act as if you don’t remember me,’ he cried, ‘–as if you don’t remember Donald Plant!’

‘I do. I remember you too . . . But it was all so long ago.’ Her voice grew hard again. ‘The taxi number is Crestwood 8484.’

On his way to the airport Donald shook his head from side to side. He was completely himself now but he could not digest the experience. Only as the plane roared up into the dark sky and its passengers became a different entity from the corporate world below did he draw a parallel from the fact of its flight. For five blinding minutes he had lived like a madman in two worlds at once. He had been a boy of twelve and a man of thirty-two, indissolubly and helplessly commingled.

Donald had lost a good deal, too, in those hours between the planes–but since the second half of life is a long process of getting rid of things, that part of the experience probably didn’t matter.

It was a wild chance but Donald was in the mood, healthy and bored, with a sense of tiresome duty done. He was now rewarding himself. Maybe.

When the plane landed he stepped out into a mid-western summer night and headed for the isolated pueblo airport, conventionalized as an old red ‘railway depot’. He did not know whether she was alive, or living in this town, or what was her present name. With mounting excitement he looked through the phone book for her father who might be dead too, somewhere in these twenty years.

No. Judge Harmon Holmes–Hillside 3194.

A woman’s amused voice answered his inquiry for Miss Nancy Holmes.

‘Nancy is Mrs Walter Gifford now. Who is this?’

But Donald hung up without answering. He had found out what he wanted to know and had only three hours. He did not remember any Walter Gifford and there was another suspended moment while he scanned the phone book. She might have married out of town.

No. Walter Gifford–Hillside 1191. Blood flowed back into his fingertips.

‘Hello?’

‘Hello. Is Mrs Gifford there–this is an old friend of hers.’

‘This is Mrs Gifford.’

He remembered, or thought he remembered, the funny magic in the voice.

‘This is Donald Plant. I haven’t seen you since I was twelve years old.’

‘Oh-h-h!’ The note was utterly surprised, very polite, but he could distinguish in it neither joy nor certain recognition.

‘Donald!’ added the voice. This time there was something more in it than struggling memory.

‘. . . when did you come back to town?’ Then cordially, ‘Where are you?’

‘I’m out at the airport–for just a few hours.’

‘Well, come up and see me.’

‘Sure you’re not just going to bed?’

‘Heavens, no!’ she exclaimed. ‘I was sitting here–having a highball by myself. Just tell your taxi man . . .’

On his way Donald analysed the conversation. His words ‘at the airport’ established that he had retained his position in the upper bourgeoisie. Nancy’s aloneness might indicate that she had matured into an unattractive woman without friends. Her husband might be either away or in bed. And–because she was always ten years old in his dreams–the highball shocked him. But he adjusted himself with a smile–she was very close to thirty.

At the end of a curved drive he saw a dark-haired little beauty standing against the lighted door, a glass in her hand. Startled by her final materialization, Donald got out of the cab, saying:

‘Mrs Gifford?’

She turned on the porch light and stared at him, wide-eyed and tentative. A smile broke through the puzzled expression.

‘Donald–it is you–we all change so. Oh, this is remarkable!’

As they walked inside, their voices jingled the words ‘all these years’, and Donald felt a sinking in his stomach. This derived in part from a vision of their last meeting–when she rode past him on a bicycle, cutting him dead–and in part from fear lest they have nothing to say. It was like a college reunion–but there the failure to find the past was disguised by the hurried boisterous occasion. Aghast, he realized that this might be a long and empty hour. He plunged in desperately.

‘You always were a lovely person. But I’m a little shocked to find you as beautiful as you are.’

It worked. The immediate recognition of their changed state, the bold compliment, made them interesting strangers instead of fumbling childhood friends.

‘Have a highball?’ she asked. ‘No? Please don’t think I’ve become a secret drinker, but this was a blue night. I expected my husband but he wired he’d be two days longer. He’s very nice, Donald, and very attractive. Rather your type and colouring.’ She hesitated, ‘–and I think he’s interested in someone in New York–and I don’t know.’

‘After seeing you it sounds impossible,’ he assured her. ‘I was married for six years, and there was a time I tortured myself that way. Then one day I just put jealousy out of my life forever. After my wife died I was very glad of that. It left a very rich memory–nothing marred or spoiled or hard to think over.’

She looked at him attentively, then sympathetically as he spoke.

‘I’m very sorry,’ she said. And after a proper moment,’ You’ve changed a lot. Turn your head. I remember father saying, «That boy has a brain.»‘

‘You probably argued against it.’

‘I was impressed. Up to then I thought everybody had a brain. That’s why it sticks in my mind.’

‘What else sticks in your mind?’ he asked smiling.

Suddenly Nancy got up and walked quickly a little away.

‘Ah, now,’ she reproached him. ‘That isn’t fair! I suppose I was a naughty girl.’

‘You were not,’ he said stoutly. ‘And I will have a drink now.’

As she poured it, her face still turned from him, he continued:

‘Do you think you were the only little girl who was ever kissed?’

‘Do you like the subject?’ she demanded. Her momentary irritation melted and she said: ‘What the hell! We did have fun. Like in the song.’

‘On the sleigh ride.’

‘Yes–and somebody’s picnic–Trudy James’s. And at Frontenac that–those summers.’

It was the sleigh ride he remembered most and kissing her cool cheeks in the straw in one corner while she laughed up at the cold white stars. The couple next to them had their backs turned and he kissed her little neck and her ears and never her lips.

‘And the Macks’ party where they played post office and I couldn’t go because I had the mumps,’ he said.

‘I don’t remember that.’

‘Oh, you were there. And you were kissed and I was crazy with jealousy like I never have been since.’

‘Funny I don’t remember. Maybe I wanted to forget.’

‘But why?’ he asked in amusement. ‘We were two perfectly innocent kids. Nancy, whenever I talked to my wife about the past, I told her you were the girl I loved almost as much as I loved her. But I think I really loved you just as much. When we moved out of town I carried you like a cannon ball in my insides.’

‘Were you that much–stirred up?’

‘My God, yes! I–‘ He suddenly realized that they were standing just two feet from each other, that he was talking as if he loved her in the present, that she was looking up at him with her lips half-parted and a clouded look in her eyes.

‘Go on,’ she said, ‘I’m ashamed to say–I like it. I didn’t know you were so upset then. I thought it was me who was upset.’

‘You!’ he exclaimed. ‘Don’t you remember throwing me over at the drugstore.’ He laughed. ‘You stuck out your tongue at me.’

‘I don’t remember at all. It seemed to me you did the throwing over.’ Her hand fell lightly, almost consolingly on his arm. ‘I’ve got a photograph book upstairs I haven’t looked at for years. I’ll dig it out.’

Donald sat for five minutes with two thoughts–first the hopeless impossibility of reconciling what different people remembered about the same event–and secondly that in a frightening way Nancy moved him as a woman as she had moved him as a child. Half an hour had developed an emotion that he had not known since the death of his wife–that he had never hoped to know again.

Side by side on a couch they opened the book between them. Nancy looked at him, smiling and very happy.

‘Oh, this is such fun,’ she said. ‘Such fun that you’re so nice, that you remember me so–beautifully. Let me tell you–I wish I’d known it then! After you’d gone I hated you.’

‘What a pity,’ he said gently.

‘But not now,’ she reassured him, and then impulsively, ‘Kiss and make up–. . . that isn’t being a good wife,’ she said after a minute. ‘I really don’t think I’ve kissed two men since I was married.’

He was excited–but most of all confused. Had he kissed Nancy? or a memory? or this lovely trembly stranger who looked away from him quickly and turned a page of the book?

‘Wait!’ he said. ‘I don’t think I could see a picture for a few seconds.’

‘We won’t do it again. I don’t feel so very calm myself.’

Donald said one of those trivial things that cover so much ground.

‘Wouldn’t it be awful if we fell in love again?’

‘Stop it!’ She laughed, but very breathlessly. ‘It’s all over. It was a moment. A moment I’ll have to forget.’

‘Don’t tell your husband.’

‘Why not? Usually I tell him everything.’

‘It’ll hurt him. Don’t ever tell a man such things.’

‘All right I won’t.’

‘Kiss me once more,’ he said inconsistently, but Nancy had turned a page and was pointing eagerly at a picture.

‘Here’s you,’ she cried. ‘Right away!’

He looked. It was a little boy in shorts standing on a pier with a sailboat in the background.

‘I remember–‘ she laughed triumphantly, ‘–the very day it was taken. Kitty took it and I stole it from her.’

For a moment Donald failed to recognize himself in the photo–then, bending closer–he failed utterly to recognize himself.

‘That’s not me,’ he said.

‘Oh yes. It was at Frontenac–the summer we–we used to go to the cave.’

‘What cave? I was only three days in Frontenac.’ Again he —strained his eyes at the slightly yellowed picture. ‘And that isn’t me. That’s Donald Bowers. We did look rather alike.’

Now she was staring at him–leaning back, seeming to lift away from him.

‘But you’re Donald Bowers!’ she exclaimed; her voice rose a little. ‘No, you’re not. You’re Donald Plant.’

‘I told you on the phone.’

She was on her feet–her face faintly horrified.

‘Plant! Bowers! I must be crazy. Or it was that drink? I was mixed up a little when I first saw you. Look here! What have I told you?’

He tried for a monkish calm as he turned a page of the book.

‘Nothing at all,’ he said. Pictures that did not include him formed and re-formed before his eyes–Frontenac–a cave–Donald Bowers–‘You threw me over!’

Nancy spoke from the other side of the room.

‘You’ll never tell this story,’ she said. ‘Stories have a way of getting around.’

‘There isn’t any story,’ he hesitated. But he thought: So she was a bad little girl.

And now suddenly he was filled with wild raging jealousy of little Donald Bowers–he who had banished jealousy from his life forever. In the five steps he took across the room he crushed out twenty years and the existence of Walter Gifford with his stride.

‘Kiss me again, Nancy,’ he said, sinking to one knee beside her chair, putting his hand upon her shoulder. But Nancy strained away.

‘You said you had to catch a plane.’

‘It’s nothing. I can miss it. It’s of no importance.’

‘Please go,’ she said in a cool voice. ‘And please try to imagine how I feel.’

‘But you act as if you don’t remember me,’ he cried, ‘–as if you don’t remember Donald Plant!’

‘I do. I remember you too . . . But it was all so long ago.’ Her voice grew hard again. ‘The taxi number is Crestwood 8484.’

On his way to the airport Donald shook his head from side to side. He was completely himself now but he could not digest the experience. Only as the plane roared up into the dark sky and its passengers became a different entity from the corporate world below did he draw a parallel from the fact of its flight. For five blinding minutes he had lived like a madman in two worlds at once. He had been a boy of twelve and a man of thirty-two, indissolubly and helplessly commingled.

Donald had lost a good deal, too, in those hours between the planes–but since the second half of life is a long process of getting rid of things, that part of the experience probably didn’t matter.

Era una idea descabellada, pero Donald estaba de humor, saludable y aburrido, con la sensación de haber cumplido con un tedioso deber. Ahora, quería su recompensa. Quizás.

Cuando el avión aterrizó, salió a una noche de verano del Medio Oeste y se dirigió al apartado aeropuerto del pueblo, conocido como una vieja y roja ‘estación de tren’. No sabía si estaba viva, ni si vivía en ese pueblo, ni cuál era su actual apellido. Con una creciente emoción, buscó en el directorio telefónico a su padre, que a lo mejor también habría muerto, en algún lugar, en esos veinte años.

Núm. Judge Harmon Holmes, Hillside 3194.

Una jovial voz femenina contestó cuando preguntó por la señorita Nancy Holmes.

—Nancy es ahora la señora (Walter) Gifford. ¿Quién habla?

Sin embargo, Donald colgó sin responder. Había descubierto lo que quería saber y solo tenía tres horas. No recordaba a ningún Walter Gifford, y hubo otro momento de suspenso mientras hojeaba el directorio telefónico. Podría haberse casado fuera del pueblo.

Núm. Walter Gifford, Hillside 1191. La sangre le volvió a la yema de los dedos.

—¿Aló?

—Aló. ¿Está la señora Gifford? Soy un viejo amigo de ella.

—Soy la señora Gifford.

Recordaba, o creyó recordar, la graciosa magia de su voz.

—Soy Donald Plant. No nos hemos visto desde que yo tenía doce años.

—¡Oh, oh, oh! —El tono era de total sorpresa, muy amable, pero no logró distinguir ni alegría ni alguna evidencia de que lo hubiera reconocido.

—¡Donald! —añadió la voz. Esta vez había algo más en su tono que una memoria en dificultad.

—¿Cuándo regresaste al pueblo? —Enseguida, de manera cordial— ¿Dónde estás?

—Estoy en las afueras del aeropuerto, solo por unas pocas horas.

—Bueno, ven a verme.

—¿Seguro que no estás a punto de acostarte?

—¡Cielos no! —exclamó—. Estaba aquí sentada tomando sola un whisky con soda. Solo dile al taxista…

Donald analizó la conversación durante el camino. Sus palabras ‘en el aeropuerto’ daban a entender que él había conservado su lugar en la alta burguesía. La soledad de Nancy podría indicar que se había convertido en una mujer poco atractiva, sin amistades. Su esposo podría estar lejos o en la cama. Y como ella siempre tendría diez años en sus sueños, lo del vaso de whisky con soda lo había impactado. Se acomodó con una sonrisa, estaría muy cerca de los treinta.

Al final de una calle curva, vio a una belleza menuda, de cabello oscuro parada contra la puerta iluminada, con un vaso en la mano. Sorprendido con su indiscutible materialización, Donald salió del taxi diciendo:

—¿Señora Gifford?

Ella encendió la luz del pórtico y se le quedo mirando, con ojos muy abiertos y dudosa. De la perpleja expresión emergió una sonrisa.

—Donald, eres tú, todos cambiamos tanto. ¡Oh, esto es extraordinario!

Mientras entraban, sus voces resonaron al decir ‘todos estos años’, y Donald sintió un nudo en el estómago. Esto sobrevino, en parte, por la visión de su último encuentro, cuando ella se le atravesó en bicicleta amenazadora; y en parte, por temor a que no tuvieran nada que decirse. Era como una reunión de la facultad, pero en ese momento la incapacidad de reanudar con el pasado quedó disimulada por la precipitada y bochornosa situación. Horrorizado, se dio cuenta de que el encuentro podría convertirse en una hora interminable y sin sentido. Se desmoronó angustiado.

—Siempre fuiste una persona encantadora; pero estoy un poco impactado de ver lo hermosa que eres.

Funcionó. El reconocimiento inmediato de haber cambiado de condición, el cumplido audaz, los convirtió en interesantes extraños en lugar de torpes amigos de la infancia.

—¿(Quieres) un whisky con soda? —preguntó—. ¿No? Por favor no pienses que me he convertido en una bebedora secreta, es que esta era una noche gris. Esperaba a mi esposo, pero me telegrafió diciendo que se tardaría dos días más. Él es muy amable, Donald, y muy atractivo. Como de tu aspecto y color de piel —vaciló—. Creo que está interesado en alguien en Nueva York, y no sé.

—Después de haberte visto, suena inconcebible—le aseguró—. Estuve casado durante seis años y en aquel entonces me torturé de tal manera. Luego, un día, arranqué los celos de mi vida para siempre. Después de la muerte de mi esposa, me alegré mucho de ello. Eso me dejó un vivo recuerdo, nada malo ni feo ni algo difícil en que pensar.

Ella lo miró con cuidado, luego con simpatía, mientras él hablaba.

—Lo siento mucho —dijo ella—. Y después de un momento prudencial—, has cambiado mucho. Voltea la cabeza. Recuerdo que mi padre decía, «ese muchacho tiene cerebro».

—A lo mejor alegaste lo contrario.

—Estaba asombrada. Hasta entonces había pensado que todo el mundo tenía un cerebro. Por eso se me quedó grabado en la cabeza.

—¿Qué otra cosa se te quedó grabada? —preguntó sonriendo.

De repente, Nancy se levantó y se alejó unos pasos deprisa.

—Ah, ya —le reprochó ella —. ¡Eso no se vale! Supongo que era una niña traviesa.

—No lo eras —dijo él con firmeza—. Y ahora quisiera una copa.

Mientras ella le servía, aún con el rostro apartado, él continuó:

—¿Crees que fuiste la única niña a la que alguna vez besaron?

—¿Te gusta el tema? —preguntó ella. Su irritación momentánea se disipó y dijo— ¡Santo cielo! Nos divertimos. Como en la canción.

—En el paseo en trineo.

—Sí, y el picnic en casa de alguien, ella de Trudy James. Y en Frontenac ese… esos veranos.

Lo que más recordaba era el paseo en trineo y el beso en sus frías mejillas, en un rincón en la paja, mientras ella se reía de las frías y blancas estrellas. La pareja de al lado estaba de espaldas, y él le beso el pequeño cuello y las orejas, pero no los labios.

—Y la fiesta de los Macks, cuando jugaron a la oficina de correos y yo no pude ir porque tenía paperas —dijo—.

—No recuerdo eso.

—¡Oh, tú estabas allí! Te besaron y yo estaba loco de celos, como nunca lo he estado desde entonces.

—Qué curioso, no lo recuerdo. A lo mejor quería olvidarlo.

—¿Pero, por qué? —preguntó divertido—. Éramos dos niños bastante inocentes. Nancy, cuando alguna vez hablé con mi esposa del pasado, le dije que tú eras la chica que había querido casi tanto como a ella. Sin embargo, creo, de verdad, que te quise mucho más. Cuando nos mudamos a las afueras del pueblo te lleve (conmigo), como una bala de cañón en las mis entrañas.

—¿Eras ése tan provocador?

—¡Por Dios, sí! Yo… —de repente, él se dio cuenta de que estaban a solo sesenta centímetros el uno del otro, que le estaba hablando como si la amara en ese instante, que ella lo estaba mirando con los labios entreabiertos y los ojos nublados.

—Continúa —dijo ella—, me da vergüenza decir que eso me gusta. No supe entonces que te hubieras sentido tan decepcionado. Pensé que era yo la decepcionada.

—¡Tú! —exclamó él—. No te acuerdas de haberme mandado a pasear en la tienda —se rio—. Me sacaste la lengua.

—No recuerdo nada. Me pareció que fuiste tú quien me mandaste a pasear —le puso la mano con suavidad sobre el brazo, casi (como) consolándolo—. Tengo un álbum de fotos arriba que no he mirado en años. Lo sacaré.

Durante cinco minutos, Donald se quedó pensando en dos cosas. La primera, la incapacidad de conciliar lo que diferentes personas recuerdan sobre un mismo evento; y la segunda que, como mujer, Nancy lo atraía de manera aterradora, tanto como cuando era niña. En media hora había aparecido una emoción que no había conocido desde la muerte de su esposa y que nunca esperóo volver a sentir.

Uno al lado del otro, en el sofá, abrieron el álbum entre los dos. Nancy lo miró sonriendo y muy contenta.

—Oh, esto es muy divertido —dijo ella—. Es muy divertido que seas tan amable, que me recuerdes tan hermosa. Déjame decirte, ¡ojalá lo hubiera sabido entonces! Después de que te fuiste te odié.

—Qué lástima —dijo él con cautela.

—Pero ahora no —le aseguró ella, y luego de manera impulsiva—, bésame y hagamos las paces. Eso no es ser una buena esposa —dijo después de un minuto—. De verdad, no recuerdo haber besado a dos hombres desde que me casé.

Estaba emocionado, pero más que todo confundido. ¿Había besado a Nancy? ¿o a un recuerdo? ¿o a esta adorable y temblorosa extraña que le apartó la mirada deprisa y volteó la página del álbum?

—¡Espera! —dijo él—. No creo que pueda ver otra foto durante unos instantes.

—No volveremos a hacerlo. No estoy muy tranquila.

Donald dijo una de esas cosas banales que dicen tanto.

—¿No sería terrible que nos volviéramos a enamorar?

—¡Basta! —rio ella, pero sin mucho aliento—. Todo se acabó. Fue un momento. Un momento que deberé olvidar.

—No se lo digas a tu esposo.

—¿Por qué no? Casi siempre le cuento todo.

—Lo puedes herir. Nunca le digas algo así a un hombre.

—Vale, no lo haré.

—Bésame otra vez —dijo él sin querer, pero Nancy había pasado una página y señalaba con ansiedad una foto.

—Aquí estás —gritó— ¡Preciso!

Miró. Era un pequeño niño en pantalones cortos, parado en un muelle con un velero al fondo.

—Recuerdo —rio victoriosa—, el mismo día en que la tomaron. Kitty la cogió y yo se la robé.

Durante un momento, Donald no logró reconocerse en la foto; entonces se acercó más y no pudo reconocerse en modo alguno.

—Ese no soy yo —dijo.

—Oh, sí. Fue en Frontenac, el verano en el que solíamos ir a la cueva.

—¿Qué cueva? Estuve solo tres días en Frontenac —de nuevo aguzó la vista hacia la imagen un tanto amarillenta—. Ese no soy yo. Es Donald Bowers. Nos parecíamos bastante.

En ese momento fue ella quien se le quedó mirando, se inclinó hacia atrás y pareció tomar distancia.

—¡Pero tú eres Donald Bowers! —exclamó; subió la voz—. No, no lo eres. Eres Donald Plant.

—Te lo dije por teléfono.

Estaba de pie, con una cara un tanto horrorizada.

—¡Plant! ¡Bowers! Debo estar loca. ¿o fue ese trago? Al comienzo estaba un poco confundida cuando te vi. ¡Mira! ¿Qué te he dicho?

Él intentó mantener una calma monacal mientras volteaba una página del álbum.

—Nada en absoluto —dijo. Imágenes donde él no estaba se formaban y volvían a formar ante sus ojos, Frontenac, una cueva, Donald Bowers— ¡Rompiste conmigo!

Nancy habló desde el otro lado de la habitación.

—No cuentes nunca esta historia —dijo—. Las historias tienen tal manera de dar vueltas.

No hay ninguna historia —vaciló; y pensó, «así que era una niña mala».

Ahora, de repente, se sintió invadido de unos celos furiosos y salvajes contra el pequeño Donald Bowers, él que había desterrado los celos para siempre de su vida. En los cinco pasos que dio a través de la habitación aplastó veinte años y la existencia de Walter Gifford de una zancada.

—Bésame otra vez, Nancy —dijo, arrodillándose junto a su silla y poniendo una mano sobre su hombro; pero Nancy se alejó.

—Dijiste que tenías que tomar un avión.

—No es nada. Puedo perderlo. No tiene importancia.

—Por favor, vete —dijo ella con voz indiferente—. Por favor, trata de imaginar cómo me siento.

¡Pero actúas como si no me recordaras —gritó—, como si no recordarás a Donald Plant!

Sí. Te recuerdo muy bien… Pero todo eso fue hace mucho tiempo —su voz volvió a endurecerse—. El número del taxi es Crestwood 8484.

Camino al aeropuerto Donald sacudió la cabeza de un lado al otro. Era de nuevo él mismo, pero no lograba digerir la experiencia. Solo cuando el avión rugió en el cielo oscuro y los pasajeros se convirtieron en una entidad diferente del mundo corporativo de abajo, trazó un paralelo con el hecho de su vuelo. Durante cinco minutos deslumbrantes había vivido como un loco en dos mundos a la vez. Había sido un niño de doce años y un hombre de treinta dos, indisolubles e imposibles de mezclar.

Donald también había perdido mucho durante esas horas entre dos aviones, pero como la segunda mitad de la vida es un largo proceso de deshacerse de las cosas, era probable que esa parte de la experiencia no importara.

Constanza Eugenia Trujillo Amaya es antropóloga de la Universidad Nacional de Colombia, doctora en Sociología de la Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, máster en Literatura y escritura creativa del Centro de Cultura Casa Lamm de México. Realizó estudios doctorales en Literatura comparada en la Universidad Complutense de Madrid, y de Historia contemporánea en las Universidades de Ginebra y l’École de hautes études en sciences sociales de París. Ha estudiado idiomas, especialmente inglés y francés, en Europa. Ha sido docente en las universidades de los Andes y Javeriana de Bogotá, y en la Universidad Católica de Lima, Perú. En la actualidad escribe ficción, cuentos, relatos y ensayos literarios, además de dedicarse a la traducción literaria del inglés y francés al español.