Sobre la memoria

Traducción del inglés por Alejandro Nájera

Texto original de Jerome K. Jerome

Edición por Magdalena Holguín

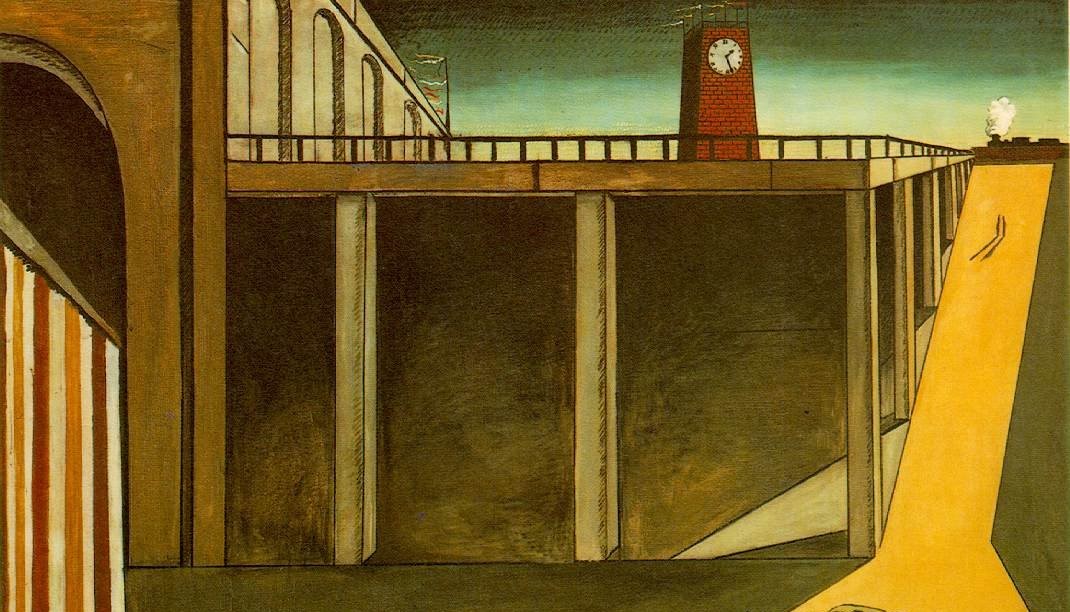

Imagen: «Gare Montparnasse (The Melancholy of Departure)» de Giorgio de Chirico

Recuerdo siempre, recuerdo siempre,

En los días del frío noviembre,

Cómo el mirlo en la…

He olvidado el resto. Es el comienzo del primer poema que me aprendí; pues el

Oye, tilín, tilín,

El gato y el violín,

no lo anoto, por tener un carácter frívolo y carecer de las cualidades de la verdadera poesía. Cobré cuatro peniques por recitar “Recuerdo siempre”. Supe que eran cuatro peniques porque me dijeron que si los guardaba hasta ganar dos peniques más tendría seis, un argumento que, si bien innegable, no me alentó, y el dinero fue derrochado, hasta donde recuerdo, a la mañana siguiente, aunque la memoria se rehúsa a decirme en qué.

Así es Memoria; nada de lo que nos trae está completo. Es una niña testaruda; todos sus juguetes están rotos. Recuerdo que, cuando era pequeño, me caí en un enorme hoyo polvoroso, pero no tengo el más mínimo recuerdo de haber salido, y si sólo confiáramos en la memoria, me vería obligado a creer que seguiría ahí.

En otra ocasión, unos años después, me encontraba en una escena de amor sumamente interesante, pero lo único que recuerdo con claridad es que, en el momento más crítico, alguien abrió la puerta de súbito y dijo: “Emily, te buscan”, con un tono sepulcral que hacía pensar que la policía había llegado por ella. Todas las tiernas palabras que me dijo y todas las bellas cosas que yo le dije han caído por completo en el olvido.

Cuando volvemos la mirada atrás, la vida en general no es más que una ruina que se desmorona: una columna destruida ahí donde se alzaba un sólido portal; el travesaño roto de una ventana para señalar la alcoba de mi mujer; un derruido montón de piedras ennegrecidas donde alguna vez saltaron las llamas relucientes y, por encima de todo, el liquen teñido y el verdor de la hiedra que se aferra.

Porque todo se vislumbra agradable a través de la atenuante neblina del tiempo. Incluso la tristeza del pasado parece dulce. Ahora los días de la niñez nos parecen muy alegres, la búsqueda de nueces, el hula-hula y el pan de jengibre. Los desaires, los dolores de muelas y los verbos en latín se han olvidado… particularmente los verbos en latín. Nos imaginamos muy felices cuando éramos traviesos y amados, y deseamos que pudiéramos volver a amar. Jamás pensamos en las angustias, en las noches de insomnio o en la ardiente sequedad en la garganta cuando ella dijo que no podía ser nada más que una hermana… ¡como si un hombre necesitara más hermanas!

Sí, es el resplandor, no la oscuridad, lo que vemos al mirar atrás. La luz del sol no proyecta sombras sobre el pasado. El camino que hemos recorrido se extiende con belleza detrás de nosotros. No vemos las piedras afiladas. Sólo nos detenemos en las rosas junto al camino, y las fuertes zarzas que nos pican son, ante nuestra mirada distante, delicados filamentos que ondean al viento. Gracias a Dios es así: que la interminable cadena de la memoria sólo tenga gratos eslabones, que la amargura y la tristeza de hoy nos traigan sonrisas mañana.

Parece como si el lado más brillante de todo fuera también el más elevado y el mejor, de modo que cuando nuestras pequeñas vidas naufragan tras nosotros en el oscuro mar del olvido, todo lo que es más luminoso y alegre es lo último en hundirse, y permanece sobre las aguas, a la vista durante mucho tiempo, mientras los pensamientos airados y el dolor agudo quedan sepultados en lo profundo de las olas y nos dejan de inquietar.

Supongo que es ese encanto del pasado lo que lleva a los viejos a decir tantas tonterías sobre los días en que eran jóvenes. El mundo parece haber sido una especie de lugar superior en aquel tiempo, cuando las cosas eran como debían ser. Entonces los niños eran niños y las niñas eran muy diferentes. También los inviernos eran algo semejante a los inviernos, y los veranos no eran en absoluto las desgracias que nos hacen pasar hoy en día. En cuanto a las maravillosas hazañas que la gente realizaba en aquellos tiempos y los extraordinarios sucesos que ocurrían, hacen falta tres hombres fornidos para creer la mitad de ellos.

Me agrada escuchar a uno de esos viejos cuando cuenta tales cosas a un grupo de jóvenes que, él sabe, no lo pueden contradecir. Es raro que, después de un rato, no jure que cuando era niño la luna brillaba todas las noches y que lanzar toros furiosos en una manta era su deporte favorito en la escuela.

Siempre ha sido y siempre será lo mismo. Los viejos de los tiempos de nuestros abuelos cantaban una canción que llevaba exactamente la misma carga, y los jóvenes de hoy dirán peroratas y tonterías similares para agraviar a la siguiente generación. “Ay, devuélvanme los buenos tiempos de hace cincuenta años”: tal ha sido la queja desde que Adán cumplió cincuenta y un años. Vuelvan a la literatura de 1835 y hallarán a poetas y novelistas pidiendo el mismo regalo imposible, como lo hicieron los Minnesänger alemanes mucho antes de ellos, y los antiguos escritores de las Sagas nórdicas mucho antes de eso. Y por lo mismo suspiraron los primeros profetas y filósofos de la antigua Grecia. Según todos los relatos, el mundo ha ido de mal en peor desde que fue creado. Todo cuanto puedo decir es que debió ser un lugar extraordinariamente encantador la primera vez que fue abierto al público, pues aun ahora es agradable si pasas todo el tiempo posible a la luz del sol, si tomas la lluvia con buen humor.

[…]

El otro día vino a verme un amigo y de manera muy elocuente me instó a aprender un prodigioso sistema mediante el cual nunca se olvida nada. No sé por qué fue tan insistente en el tema, a menos que sea porque de vez en cuando pido prestado un paraguas y tengo la manía de salir, en medio de un juego de whist, con un sutil “¡Señor!, todo este tiempo había pensado que los tréboles eran corazones”. Sin embargo, decliné la recomendación a pesar de las ventajas que tan atractivamente me planteó. No tengo ningún deseo de recordar todo. Hay muchas cosas en la vida de los hombres que es mejor olvidar. He ahí esa ocasión, hace muchos años, en que no actuamos con tanto honor, con tanta rectitud, como quizá debimos hacerlo: esa desafortunada desviación del estricto camino de la probidad en la que alguna vez incurrimos y en la que, de manera aun más desafortunada, fuimos descubiertos, aquel acto de estupidez, de mezquindad, de equivocación. ¡Ah, bueno!, y pagamos la pena, sufrimos las exasperantes horas de vano remordimiento, la ardiente agonía de la vergüenza, quizá el desprecio de quienes amamos. Olvidemos. Sí, Padre Tiempo, retira con tus bondadosas manos esos recuerdos amargos de nuestro agobiado corazón, pues las penas siempre nos llegan con las horas y nuestra fuerza es tan limitada como el día.

No se trata de enterrar el pasado. La música de la vida caería en el silencio si se rompieran las cuerdas de la memoria. Es la maleza ponzoñosa, y no las flores, la que debería ser arrancada del jardín de Mnemosine. ¿Recuerdan “El hechizado” de Dickens?: cómo suplicaba por olvidar y, cuando su plegaria fue escuchada, cómo suplicaba otra vez por recordar. No queremos echar a todos los fantasmas, sólo a los demacrados espectros de cruel mirada de los que solemos huir. Que los fantasmas amables y benévolos nos persigan como gusten; a esos no les tememos.

¡Ay de mí!, el mundo se colma de fantasmas conforme envejecemos. No es necesario buscar en lúgubres cementerios ni dormir en fincas amuralladas para ver sus rostros sombríos y escuchar el susurro de sus ropas en la noche. Cada casa, cada habitación, cada silla que rechina tiene su propio fantasma. Acechan las cámaras vacías de nuestras vidas, se amontonan a nuestro alrededor como hojas muertas revueltas por el viento otoñal. Algunos están vivos, algunos están muertos. No lo sabemos. Alguna vez estrechamos sus manos, los amamos, reñimos con ellos, reímos con ellos, les contamos nuestros pensamientos, esperanzas y aspiraciones, como ellos nos contaban las suyas, hasta que parecía que nuestros corazones se habían unido con un lazo que desafiaría el frágil poder de la Muerte. Ahora se han ido, se han perdido para siempre. Sus ojos jamás volverán a mirar los nuestros y jamás volveremos a oír sus voces. Los vemos, tenues y sombríos, a través de las lágrimas. Tendemos con anhelo las manos hacia ellos, pero sólo son aire.

¡Fantasmas! Están con nosotros día y noche. Caminan a nuestro lado en la calle concurrida, bajo el resplandor del sol. Se sientan con nosotros en la casa a la hora del crepúsculo. Vemos sus caritas mirándonos desde las ventanas de la vieja escuela. Los encontramos en el bosque y en las callejuelas donde gritábamos y jugábamos de niños. ¡Escucha! ¿No oyes sus quedas risas detrás de las zarzas y sus gritos distantes a lo largo de los claros poblados de hierba? Justo allí, entre los tranquilos campos y junto al bosque, donde merodean las sombras del anochecer, serpentea la vereda donde solíamos verla a ella al caer el sol. Mírala, ahí está ahora, con el delicado vestido blanco que tan bien conocíamos, el enorme gorro que colgaba de sus manitas y su soleado cabello castaño, todo enmarañado. ¡A ocho mil kilómetros de distancia! ¡Ha muerto, por lo que sabemos! ¿Y qué? Ahora está junto a nosotros y podemos ver sus ojos sonrientes y escuchar su voz. Desaparecerá en los escalones de la cerca junto al bosque y nos quedaremos solos; las sombras se arrastrarán por los campos y el viento nocturno se llevará los lamentos del pasado. ¡Fantasmas! Siempre estarán con nosotros, siempre estarán mientras el triste y viejo mundo siga resonando con el sollozo de los largos adioses, mientras los crueles barcos se alejen navegando los inmensos mares y la tierra fría extienda su verdor con pesadez sobre los corazones de quienes amamos.

[…]

La memoria es una extraña invocadora de fantasmas. Como una casa embrujada, sus paredes en todo momento propagan los ecos de pies invisibles. Por las ventanas rotas miramos las sombras escurridizas de los muertos, y las sombras más tristes son aquellas de nuestro propio ser que ha muerto.

Ah, esos rostros jóvenes y brillantes, tan llenos de verdad y honor, de pensamientos puros y buenos, de nobles anhelos, ¡cómo nos reprochan al mirarnos con sus ojos profundos y claros!

Pobres muchachos, me temo que tienen buenas razones para sufrir. Las mentiras, la malicia y el recelo se han arrastrado a nuestro corazón desde antes de afeitarnos… y pretendíamos ser tan grandiosos y buenos. Es bueno que no podamos ver el futuro. Muy pocos muchachos de catorce años se sentirían orgullosos de sí mismos a los cuarenta.

A veces me gusta sentarme a platicar con aquel chico raro que era yo hace mucho tiempo. Creo que a él también le agrada, pues muy a menudo viene al anochecer, cuando estoy solo con mi pipa, escuchando el susurro de las llamas. Veo su carita solemne, mirándome entre el fragante humo que sube flotando; le sonrío y él me sonríe también, pero la suya es una sonrisa grave, anticuada. Hablamos de los viejos tiempos. De vez en cuando me toma de la mano y nos deslizamos entre las negras rejillas de la chimenea y bajamos por las oscuras cuevas que refulgen hasta la tierra que se extiende tras la luz del fuego. Ahí hallamos los días del pasado y los recorremos juntos. Mientras caminamos, me cuenta todo cuanto piensa y siente. A veces me río de él, pero al siguiente instante me arrepiento, pues adopta un semblante tan serio que me avergüenzo de mi frivolidad. Eso, además, no es mostrar el debido respeto a alguien mucho mayor que yo, a ese que era yo mucho antes de que me volviera quien soy.

Al principio no hablamos mucho, sino que nos miramos; yo bajo la mirada hacia su cabello ondulado y su corbatita azul, él me mira de soslayo mientras trota. Por algún motivo imagino que esos ojos tímidos y redondos no me aprueban del todo, y exhala un breve suspiro, como si estuviera decepcionado. Pero después de un rato su timidez desaparece y comienza a platicar. Me cuenta sus relatos de hadas favoritos, hasta seis veces, y que tiene un cuyo, y que papá dice que los cuentos de hadas no son reales; ¿no es una pena? Porque le gustaría ser caballero para luchar contra un dragón y casarse con una bella princesa. Pero al cumplir siete años adopta una visión más práctica de la vida, pues de grande preferiría ser gabarrero y ganar mucho dinero. Quizá eso se debe a que se ha enamorado, justo en ese tiempo, de la damita de la lechería, que tiene seis años. (¡Dios bendiga sus piececitos bailarines, cualquiera que sea su tamaño ahora!). Debe de tenerle mucho cariño, pues un día le regala su mayor tesoro: una enorme navaja con cuatro hojas oxidadas y un sacacorchos, el cual tiene la misteriosa manía de salirse para clavarse en la pierna de su dueño. Ella es una pequeña cariñosa, le echa los brazos al cuello y lo besa por el regalo, allí mismo, afuera de la tienda. Pero el mundo estúpido (en la persona del niño del emporio de cigarros que está al lado) se burla de esas muestras de amor. Es por eso que mi joven amigo se dispone muy propiamente a golpear la cabeza del niño del emporio de cigarros, pero falla en su intento y el niño del emporio de cigarros golpea la cabeza de él.

Luego llega la vida escolar, con sus pequeñas y amargas tristezas, sus gritos de júbilo, sus felices jolgorios y sus lágrimas cálidas que caen sobre las horribles gramáticas de latín y los viejos cuadernos tontos. Es en la escuela donde queda herido de por vida, al tratar, como firmemente lo creo, de pronunciar el alemán; es ahí, también, donde aprende la importancia que la nación francesa da a las plumas, a la tinta y al papel. “¿Tiene plumas, tinta y papel?” es la primera pregunta que le hace un francés a otro cuando se conocen.

[…]

De modo que en la adquisición de un conocimiento más o menos inútil, que pronto será felizmente olvidado, se va la infancia. La escuela de ladrillos rojos se esfuma de la vista y tomamos el camino del mundo. Entonces mi amiguito ya no es pequeño. A la chaqueta le ha brotado un faldón. La gorra maltrecha, que tan bien combinaba con el pañuelo de bolsillo, el vaso para beber y el arma de ataque, se ha vuelto alta y lustrosa, y en lugar del lápiz en la boca lleva un cigarrillo, cuyo humo le molesta porque le sube hasta la nariz. Poco después prueba un puro, por ser más elegante: un enorme habano negro. Parece que no le cae muy bien, pues más tarde lo encuentro sentado en un balde de la cocina trasera, jurando solemnemente no volver a fumar.

Ahora el bigote se le empieza a notar casi a simple vista, con lo cual se aficiona de inmediato al brandy con soda y se cree un hombre. Habla de “dos a uno contra el favorito”, se refiere a las actrices como “la chiquilla Emmy”, “Kate” y “la Beba”, y murmura acerca de lo que “la otra noche perdió en los naipes”, con un estilo que implica que ha derrochado miles, aunque, para hacerle justicia, muy probablemente la cantidad verdadera sea un chelín con dos peniques. Si veo bien —pues en esta tierra de los recuerdos permanece el ocaso—, también lleva un monóculo en el ojo y tropieza con todo.

Sus amigas, con las que mantiene relaciones muy problemáticas, rezan por él (¡benditos sean sus dulces corazones!) y presagian juicios en Old Bailey y cabestrillos como único resultado posible de esa disipación tan insensata; la predicción de su primer maestro escolar, quien dijo que terminaría mal, adquiere las proporciones de una inspirada profecía.

A esa edad siente un desprecio señorial por el sexo opuesto, tiene una opinión descaradamente positiva de él mismo y en sociedad trata de manera condescendiente a los ancianos que son amigos de la familia. En general, hay que confesarlo, en aquella época es algo irritante.

Pero eso no dura mucho. Al poco tiempo se enamora, lo cual pronto le quita el vigor. Advierto que ahora sus botas son demasiado pequeñas para él y que se arregla el cabello con sumo y estupendo cuidado. Lee más poesía que antes y guarda un diccionario de rimas en su habitación. Todas las mañanas, Emily Jane encuentra en el piso trozos de papel en los que se lee sobre “corazones crueles y profundos dardos de amor”, sobre “bellos ojos y suspiros de amantes” y aun más sobre canciones muy, muy viejas que los muchachos adoran cantar y las muchachas adoran escuchar mientras sacuden sus delicadas cabezas, fingiendo no escuchar.

Sin embargo, el curso del amor no parece haber transcurrido sin contratiempos, pues, pobre muchacho, más tarde se ejercita dando paseos más largos y duerme menos de lo que le conviene; en su rostro se percibe cualquier cosa salvo campanas de boda y felicidad por siempre.

En este punto parece desvanecerse. El pequeño yo de la infancia que creció a mi lado mientras caminábamos ha partido.

Estoy solo y el camino es muy oscuro. Sigo tropezando, no sé cómo ni me importa, pues este rumbo parece no llevar a ningún lado y no hay luz alguna que me guíe.

Pero al fin llega la mañana y descubro que he crecido hasta ser quien soy.

I remember, I remember,

In the days of chill November,

How the blackbird on the—

I forget the rest. It is the beginning of the first piece of poetry I ever learned; for

Hey, diddle diddle,

The cat and the fiddle,

I take no note of, it being of a frivolous character and lacking in the qualities of true poetry. I collected fourpence by the recital of “I remember, I remember.” I knew it was fourpence, because they told me that if I kept it until I got twopence more I should have sixpence, which argument, albeit undeniable, moved me not, and the money was squandered, to the best of my recollection, on the very next morning, although upon what memory is a blank.

That is just the way with Memory; nothing that she brings to us is complete. She is a willful child; all her toys are broken. I remember tumbling into a huge dust-hole when a very small boy, but I have not the faintest recollection of ever getting out again; and if memory were all we had to trust to, I should be compelled to believe I was there still.

At another time—some years later—I was assisting at an exceedingly interesting love scene; but the only thing about it I can call to mind distinctly is that at the most critical moment somebody suddenly opened the door and said, “Emily, you’re wanted,” in a sepulchral tone that gave one the idea the police had come for her. All the tender words she said to me and all the beautiful things I said to her are utterly forgotten.

Life altogether is but a crumbling ruin when we turn to look behind: a shattered column here, where a massive portal stood; the broken shaft of a window to mark my lady’s bower; and a moldering heap of blackened stones where the glowing flames once leaped, and over all the tinted lichen and the ivy clinging green.

For everything looms pleasant through the softening haze of time. Even the sadness that is past seems sweet. Our boyish days look very merry to us now, all nutting, hoop, and gingerbread. The snubbings and toothaches and the Latin verbs are all forgotten—the Latin verbs especially. And we fancy we were very happy when we were hobbledehoys and loved; and we wish that we could love again. We never think of the heartaches, or the sleepless nights, or the hot dryness of our throats, when she said she could never be anything to us but a sister—as if any man wanted more sisters!

Yes, it is the brightness, not the darkness, that we see when we look back. The sunshine casts no shadows on the past. The road that we have traversed stretches very fair behind us. We see not the sharp stones. We dwell but on the roses by the wayside, and the strong briers that stung us are, to our distant eyes, but gentle tendrils waving in the wind. God be thanked that it is so—that the ever-lengthening chain of memory has only pleasant links, and that the bitterness and sorrow of to-day are smiled at on the morrow.

It seems as though the brightest side of everything were also its highest and best, so that as our little lives sink back behind us into the dark sea of forgetfulness, all that which is the lightest and the most gladsome is the last to sink, and stands above the waters, long in sight, when the angry thoughts and smarting pain are buried deep below the waves and trouble us no more.

It is this glamour of the past, I suppose, that makes old folk talk so much nonsense about the days when they were young. The world appears to have been a very superior sort of place then, and things were more like what they ought to be. Boys were boys then, and girls were very different. Also winters were something like winters, and summers not at all the wretched-things we get put off with nowadays. As for the wonderful deeds people did in those times and the extraordinary events that happened, it takes three strong men to believe half of them.

I like to hear one of the old boys telling all about it to a party of youngsters who he knows cannot contradict him. It is odd if, after awhile, he doesn’t swear that the moon shone every night when he was a boy, and that tossing mad bulls in a blanket was the favorite sport at his school.

It always has been and always will be the same. The old folk of our grandfathers’ young days sang a song bearing exactly the same burden; and the young folk of to-day will drone out precisely similar nonsense for the aggravation of the next generation. “Oh, give me back the good old days of fifty years ago,” has been the cry ever since Adam’s fifty-first birthday. Take up the literature of 1835, and you will find the poets and novelists asking for the same impossible gift as did the German Minnesingers long before them and the old Norse Saga writers long before that. And for the same thing sighed the early prophets and the philosophers of ancient Greece. From all accounts, the world has been getting worse and worse ever since it was created. All I can say is that it must have been a remarkably delightful place when it was first opened to the public, for it is very pleasant even now if you only keep as much as possible in the sunshine and take the rain good-temperedly.

[…]

A friend came to me the other day and urged me very eloquently to learn some wonderful system by which you never forgot anything. I don’t know why he was so eager on the subject, unless it be that I occasionally borrow an umbrella and have a knack of coming out, in the middle of a game of whist, with a mild “Lor! I’ve been thinking all along that clubs were trumps.” I declined the suggestion, however, in spite of the advantages he so attractively set forth. I have no wish to remember everything. There are many things in most men’s lives that had better be forgotten. There is that time, many years ago, when we did not act quite as honorably, quite as uprightly, as we perhaps should have done—that unfortunate deviation from the path of strict probity we once committed, and in which, more unfortunate still, we were found out—that act of folly, of meanness, of wrong. Ah, well! we paid the penalty, suffered the maddening hours of vain remorse, the hot agony of shame, the scorn, perhaps, of those we loved. Let us forget. Oh, Father Time, lift with your kindly hands those bitter memories from off our overburdened hearts, for griefs are ever coming to us with the coming hours, and our little strength is only as the day.

Not that the past should be buried. The music of life would be mute if the chords of memory were snapped asunder. It is but the poisonous weeds, not the flowers, that we should root out from the garden of Mnemosyne. Do you remember Dickens’ “Haunted Man”—how he prayed for forgetfulness, and how, when his prayer was answered, he prayed for memory once more? We do not want all the ghosts laid. It is only the haggard, cruel-eyed specters that we flee from. Let the gentle, kindly phantoms haunt us as they will; we are not afraid of them.

Ah me! the world grows very full of ghosts as we grow older. We need not seek in dismal church-yards nor sleep in moated granges to see the shadowy faces and hear the rustling of their garments in the night. Every house, every room, every creaking chair has its own particular ghost. They haunt the empty chambers of our lives, they throng around us like dead leaves whirled in the autumn wind. Some are living, some are dead. We know not. We clasped their hands once, loved them, quarreled with them, laughed with them, told them our thoughts and hopes and aims, as they told us theirs, till it seemed our very hearts had joined in a grip that would defy the puny power of Death. They are gone now; lost to us forever. Their eyes will never look into ours again and their voices we shall never hear. Only their ghosts come to us and talk with us. We see them, dim and shadowy, through our tears. We stretch our yearning hands to them, but they are air.

Ghosts! They are with us night and day. They walk beside us in the busy street under the glare of the sun. They sit by us in the twilight at home. We see their little faces looking from the windows of the old school-house. We meet them in the woods and lanes where we shouted and played as boys. Hark! cannot you hear their low laughter from behind the blackberry-bushes and their distant whoops along the grassy glades? Down here, through the quiet fields and by the wood, where the evening shadows are lurking, winds the path where we used to watch for her at sunset. Look, she is there now, in the dainty white frock we knew so well, with the big bonnet dangling from her little hands and the sunny brown hair all tangled. Five thousand miles away! Dead for all we know! What of that? She is beside us now, and we can look into her laughing eyes and hear her voice. She will vanish at the stile by the wood and we shall be alone; and the shadows will creep out across the fields and the night wind will sweep past moaning. Ghosts! they are always with us and always will be while the sad old world keeps echoing to the sob of long good-bys, while the cruel ships sail away across the great seas, and the cold green earth lies heavy on the hearts of those we loved.

[…]

Memory is a rare ghost-raiser. Like a haunted house, its walls are ever echoing to unseen feet. Through the broken casements we watch the flitting shadows of the dead, and the saddest shadows of them all are the shadows of our own dead selves.

Oh, those young bright faces, so full of truth and honor, of pure, good thoughts, of noble longings, how reproachfully they look upon us with their deep, clear eyes!

I fear they have good cause for their sorrow, poor lads. Lies and cunning and disbelief have crept into our hearts since those preshaving days—and we meant to be so great and good.

It is well we cannot see into the future. There are few boys of fourteen who would not feel ashamed of themselves at forty.

I like to sit and have a talk sometimes with that odd little chap that was myself long ago. I think he likes it too, for he comes so often of an evening when I am alone with my pipe, listening to the whispering of the flames. I see his solemn little face looking at me through the scented smoke as it floats upward, and I smile at him; and he smiles back at me, but his is such a grave, old-fashioned smile. We chat about old times; and now and then he takes me by the hand, and then we slip through the black bars of the grate and down the dusky glowing caves to the land that lies behind the firelight. There we find the days that used to be, and we wander along them together. He tells me as we walk all he thinks and feels. I laugh at him now and then, but the next moment I wish I had not, for he looks so grave I am ashamed of being frivolous. Besides, it is not showing proper respect to one so much older than myself—to one who was myself so very long before I became myself.

We don’t talk much at first, but look at one another; I down at his curly hair and little blue bow, he up sideways at me as he trots. And some-how I fancy the shy, round eyes do not altogether approve of me, and he heaves a little sigh, as though he were disappointed. But after awhile his bashfulness wears off and he begins to chat. He tells me his favorite fairy-tales, he can do up to six times, and he has a guinea-pig, and pa says fairy-tales ain’t true; and isn’t it a pity? ‘cos he would so like to be a knight and fight a dragon and marry a beautiful princess. But he takes a more practical view of life when he reaches seven, and would prefer to grow up be a bargee, and earn a lot of money. Maybe this is the consequence of falling in love, which he does about this time with the young lady at the milk shop aet. six. (God bless her little ever-dancing feet, whatever size they may be now!) He must be very fond of her, for he gives her one day his chiefest treasure, to wit, a huge pocket-knife with four rusty blades and a corkscrew, which latter has a knack of working itself out in some mysterious manner and sticking into its owner’s leg. She is an affectionate little thing, and she throws her arms round his neck and kisses him for it, then and there, outside the shop. But the stupid world (in the person of the boy at the cigar emporium next door) jeers at such tokens of love. Whereupon my young friend very properly prepares to punch the head of the boy at the cigar emporium next door; but fails in the attempt, the boy at the cigar emporium next door punching his instead.

And then comes school life, with its bitter little sorrows and its joyous shoutings, its jolly larks, and its hot tears falling on beastly Latin grammars and silly old copy-books. It is at school that he injures himself for life—as I firmly believe—trying to pronounce German; and it is there, too, that he learns of the importance attached by the French nation to pens, ink, and paper. “Have you pens, ink, and paper?” is the first question asked by one Frenchman of another on their meeting.

[…]

So in the acquisition of more or less useless knowledge, soon happily to be forgotten, boyhood passes away. The red-brick school-house fades from view, and we turn down into the world’s high-road. My little friend is no longer little now. The short jacket has sprouted tails. The battered cap, so useful as a combination of pocket-handkerchief, drinking-cup, and weapon of attack, has grown high and glossy; and instead of a slate-pencil in his mouth there is a cigarette, the smoke of which troubles him, for it will get up his nose. He tries a cigar a little later on as being more stylish—a big black Havanna. It doesn’t seem altogether to agree with him, for I find him sitting over a bucket in the back kitchen afterward, solemnly swearing never to smoke again.

And now his mustache begins to be almost visible to the naked eye, whereupon he immediately takes to brandy-and-sodas and fancies himself a man. He talks about “two to one against the favorite,” refers to actresses as “Little Emmy” and “Kate” and “Baby,” and murmurs about his “losses at cards the other night” in a style implying that thousands have been squandered, though, to do him justice, the actual amount is most probably one-and-twopence. Also, if I see aright—for it is always twilight in this land of memories—he sticks an eyeglass in his eye and stumbles over everything.

His female relations, much troubled at these things, pray for him (bless their gentle hearts!) and see visions of Old Bailey trials and halters as the only possible outcome of such reckless dissipation; and the prediction of his first school-master, that he would come to a bad end, assumes the proportions of inspired prophecy.

He has a lordly contempt at this age for the other sex, a blatantly good opinion of himself, and a sociably patronizing manner toward all the elderly male friends of the family. Altogether, it must be confessed, he is somewhat of a nuisance about this time.

It does not last long, though. He falls in love in a little while, and that soon takes the bounce out of him. I notice his boots are much too small for him now, and his hair is fearfully and wonderfully arranged. He reads poetry more than he used, and he keeps a rhyming dictionary in his bedroom. Every morning Emily Jane finds scraps of torn-up paper on the floor and reads thereon of “cruel hearts and love’s deep darts,” of “beauteous eyes and lovers’ sighs,” and much more of the old, old song that lads so love to sing and lassies love to listen to while giving their dainty heads a toss and pretending never to hear.

The course of love, however, seems not to have run smoothly, for later on he takes more walking exercise and less sleep, poor boy, than is good for him; and his face is suggestive of anything but wedding-bells and happiness ever after.

And here he seems to vanish. The little, boyish self that has grown up beside me as we walked is gone.

I am alone and the road is very dark. I stumble on, I know not how nor care, for the way seems leading nowhere, and there is no light to guide.

But at last the morning comes, and I find that I have grown into myself.

I remember, I remember,

In the days of chill November,

How the blackbird on the—

I forget the rest. It is the beginning of the first piece of poetry I ever learned; for

Hey, diddle diddle,

The cat and the fiddle,

I take no note of, it being of a frivolous character and lacking in the qualities of true poetry. I collected fourpence by the recital of “I remember, I remember.” I knew it was fourpence, because they told me that if I kept it until I got twopence more I should have sixpence, which argument, albeit undeniable, moved me not, and the money was squandered, to the best of my recollection, on the very next morning, although upon what memory is a blank.

That is just the way with Memory; nothing that she brings to us is complete. She is a willful child; all her toys are broken. I remember tumbling into a huge dust-hole when a very small boy, but I have not the faintest recollection of ever getting out again; and if memory were all we had to trust to, I should be compelled to believe I was there still.

At another time—some years later—I was assisting at an exceedingly interesting love scene; but the only thing about it I can call to mind distinctly is that at the most critical moment somebody suddenly opened the door and said, “Emily, you’re wanted,” in a sepulchral tone that gave one the idea the police had come for her. All the tender words she said to me and all the beautiful things I said to her are utterly forgotten.

Life altogether is but a crumbling ruin when we turn to look behind: a shattered column here, where a massive portal stood; the broken shaft of a window to mark my lady’s bower; and a moldering heap of blackened stones where the glowing flames once leaped, and over all the tinted lichen and the ivy clinging green.

For everything looms pleasant through the softening haze of time. Even the sadness that is past seems sweet. Our boyish days look very merry to us now, all nutting, hoop, and gingerbread. The snubbings and toothaches and the Latin verbs are all forgotten—the Latin verbs especially. And we fancy we were very happy when we were hobbledehoys and loved; and we wish that we could love again. We never think of the heartaches, or the sleepless nights, or the hot dryness of our throats, when she said she could never be anything to us but a sister—as if any man wanted more sisters!

Yes, it is the brightness, not the darkness, that we see when we look back. The sunshine casts no shadows on the past. The road that we have traversed stretches very fair behind us. We see not the sharp stones. We dwell but on the roses by the wayside, and the strong briers that stung us are, to our distant eyes, but gentle tendrils waving in the wind. God be thanked that it is so—that the ever-lengthening chain of memory has only pleasant links, and that the bitterness and sorrow of to-day are smiled at on the morrow.

It seems as though the brightest side of everything were also its highest and best, so that as our little lives sink back behind us into the dark sea of forgetfulness, all that which is the lightest and the most gladsome is the last to sink, and stands above the waters, long in sight, when the angry thoughts and smarting pain are buried deep below the waves and trouble us no more.

It is this glamour of the past, I suppose, that makes old folk talk so much nonsense about the days when they were young. The world appears to have been a very superior sort of place then, and things were more like what they ought to be. Boys were boys then, and girls were very different. Also winters were something like winters, and summers not at all the wretched-things we get put off with nowadays. As for the wonderful deeds people did in those times and the extraordinary events that happened, it takes three strong men to believe half of them.

I like to hear one of the old boys telling all about it to a party of youngsters who he knows cannot contradict him. It is odd if, after awhile, he doesn’t swear that the moon shone every night when he was a boy, and that tossing mad bulls in a blanket was the favorite sport at his school.

It always has been and always will be the same. The old folk of our grandfathers’ young days sang a song bearing exactly the same burden; and the young folk of to-day will drone out precisely similar nonsense for the aggravation of the next generation. “Oh, give me back the good old days of fifty years ago,” has been the cry ever since Adam’s fifty-first birthday. Take up the literature of 1835, and you will find the poets and novelists asking for the same impossible gift as did the German Minnesingers long before them and the old Norse Saga writers long before that. And for the same thing sighed the early prophets and the philosophers of ancient Greece. From all accounts, the world has been getting worse and worse ever since it was created. All I can say is that it must have been a remarkably delightful place when it was first opened to the public, for it is very pleasant even now if you only keep as much as possible in the sunshine and take the rain good-temperedly.

[…]

A friend came to me the other day and urged me very eloquently to learn some wonderful system by which you never forgot anything. I don’t know why he was so eager on the subject, unless it be that I occasionally borrow an umbrella and have a knack of coming out, in the middle of a game of whist, with a mild “Lor! I’ve been thinking all along that clubs were trumps.” I declined the suggestion, however, in spite of the advantages he so attractively set forth. I have no wish to remember everything. There are many things in most men’s lives that had better be forgotten. There is that time, many years ago, when we did not act quite as honorably, quite as uprightly, as we perhaps should have done—that unfortunate deviation from the path of strict probity we once committed, and in which, more unfortunate still, we were found out—that act of folly, of meanness, of wrong. Ah, well! we paid the penalty, suffered the maddening hours of vain remorse, the hot agony of shame, the scorn, perhaps, of those we loved. Let us forget. Oh, Father Time, lift with your kindly hands those bitter memories from off our overburdened hearts, for griefs are ever coming to us with the coming hours, and our little strength is only as the day.

Not that the past should be buried. The music of life would be mute if the chords of memory were snapped asunder. It is but the poisonous weeds, not the flowers, that we should root out from the garden of Mnemosyne. Do you remember Dickens’ “Haunted Man”—how he prayed for forgetfulness, and how, when his prayer was answered, he prayed for memory once more? We do not want all the ghosts laid. It is only the haggard, cruel-eyed specters that we flee from. Let the gentle, kindly phantoms haunt us as they will; we are not afraid of them.

Ah me! the world grows very full of ghosts as we grow older. We need not seek in dismal church-yards nor sleep in moated granges to see the shadowy faces and hear the rustling of their garments in the night. Every house, every room, every creaking chair has its own particular ghost. They haunt the empty chambers of our lives, they throng around us like dead leaves whirled in the autumn wind. Some are living, some are dead. We know not. We clasped their hands once, loved them, quarreled with them, laughed with them, told them our thoughts and hopes and aims, as they told us theirs, till it seemed our very hearts had joined in a grip that would defy the puny power of Death. They are gone now; lost to us forever. Their eyes will never look into ours again and their voices we shall never hear. Only their ghosts come to us and talk with us. We see them, dim and shadowy, through our tears. We stretch our yearning hands to them, but they are air.

Ghosts! They are with us night and day. They walk beside us in the busy street under the glare of the sun. They sit by us in the twilight at home. We see their little faces looking from the windows of the old school-house. We meet them in the woods and lanes where we shouted and played as boys. Hark! cannot you hear their low laughter from behind the blackberry-bushes and their distant whoops along the grassy glades? Down here, through the quiet fields and by the wood, where the evening shadows are lurking, winds the path where we used to watch for her at sunset. Look, she is there now, in the dainty white frock we knew so well, with the big bonnet dangling from her little hands and the sunny brown hair all tangled. Five thousand miles away! Dead for all we know! What of that? She is beside us now, and we can look into her laughing eyes and hear her voice. She will vanish at the stile by the wood and we shall be alone; and the shadows will creep out across the fields and the night wind will sweep past moaning. Ghosts! they are always with us and always will be while the sad old world keeps echoing to the sob of long good-bys, while the cruel ships sail away across the great seas, and the cold green earth lies heavy on the hearts of those we loved.

[…]

Memory is a rare ghost-raiser. Like a haunted house, its walls are ever echoing to unseen feet. Through the broken casements we watch the flitting shadows of the dead, and the saddest shadows of them all are the shadows of our own dead selves.

Oh, those young bright faces, so full of truth and honor, of pure, good thoughts, of noble longings, how reproachfully they look upon us with their deep, clear eyes!

I fear they have good cause for their sorrow, poor lads. Lies and cunning and disbelief have crept into our hearts since those preshaving days—and we meant to be so great and good.

It is well we cannot see into the future. There are few boys of fourteen who would not feel ashamed of themselves at forty.

I like to sit and have a talk sometimes with that odd little chap that was myself long ago. I think he likes it too, for he comes so often of an evening when I am alone with my pipe, listening to the whispering of the flames. I see his solemn little face looking at me through the scented smoke as it floats upward, and I smile at him; and he smiles back at me, but his is such a grave, old-fashioned smile. We chat about old times; and now and then he takes me by the hand, and then we slip through the black bars of the grate and down the dusky glowing caves to the land that lies behind the firelight. There we find the days that used to be, and we wander along them together. He tells me as we walk all he thinks and feels. I laugh at him now and then, but the next moment I wish I had not, for he looks so grave I am ashamed of being frivolous. Besides, it is not showing proper respect to one so much older than myself—to one who was myself so very long before I became myself.

We don’t talk much at first, but look at one another; I down at his curly hair and little blue bow, he up sideways at me as he trots. And some-how I fancy the shy, round eyes do not altogether approve of me, and he heaves a little sigh, as though he were disappointed. But after awhile his bashfulness wears off and he begins to chat. He tells me his favorite fairy-tales, he can do up to six times, and he has a guinea-pig, and pa says fairy-tales ain’t true; and isn’t it a pity? ‘cos he would so like to be a knight and fight a dragon and marry a beautiful princess. But he takes a more practical view of life when he reaches seven, and would prefer to grow up be a bargee, and earn a lot of money. Maybe this is the consequence of falling in love, which he does about this time with the young lady at the milk shop aet. six. (God bless her little ever-dancing feet, whatever size they may be now!) He must be very fond of her, for he gives her one day his chiefest treasure, to wit, a huge pocket-knife with four rusty blades and a corkscrew, which latter has a knack of working itself out in some mysterious manner and sticking into its owner’s leg. She is an affectionate little thing, and she throws her arms round his neck and kisses him for it, then and there, outside the shop. But the stupid world (in the person of the boy at the cigar emporium next door) jeers at such tokens of love. Whereupon my young friend very properly prepares to punch the head of the boy at the cigar emporium next door; but fails in the attempt, the boy at the cigar emporium next door punching his instead.

And then comes school life, with its bitter little sorrows and its joyous shoutings, its jolly larks, and its hot tears falling on beastly Latin grammars and silly old copy-books. It is at school that he injures himself for life—as I firmly believe—trying to pronounce German; and it is there, too, that he learns of the importance attached by the French nation to pens, ink, and paper. “Have you pens, ink, and paper?” is the first question asked by one Frenchman of another on their meeting.

[…]

So in the acquisition of more or less useless knowledge, soon happily to be forgotten, boyhood passes away. The red-brick school-house fades from view, and we turn down into the world’s high-road. My little friend is no longer little now. The short jacket has sprouted tails. The battered cap, so useful as a combination of pocket-handkerchief, drinking-cup, and weapon of attack, has grown high and glossy; and instead of a slate-pencil in his mouth there is a cigarette, the smoke of which troubles him, for it will get up his nose. He tries a cigar a little later on as being more stylish—a big black Havanna. It doesn’t seem altogether to agree with him, for I find him sitting over a bucket in the back kitchen afterward, solemnly swearing never to smoke again.

And now his mustache begins to be almost visible to the naked eye, whereupon he immediately takes to brandy-and-sodas and fancies himself a man. He talks about “two to one against the favorite,” refers to actresses as “Little Emmy” and “Kate” and “Baby,” and murmurs about his “losses at cards the other night” in a style implying that thousands have been squandered, though, to do him justice, the actual amount is most probably one-and-twopence. Also, if I see aright—for it is always twilight in this land of memories—he sticks an eyeglass in his eye and stumbles over everything.

His female relations, much troubled at these things, pray for him (bless their gentle hearts!) and see visions of Old Bailey trials and halters as the only possible outcome of such reckless dissipation; and the prediction of his first school-master, that he would come to a bad end, assumes the proportions of inspired prophecy.

He has a lordly contempt at this age for the other sex, a blatantly good opinion of himself, and a sociably patronizing manner toward all the elderly male friends of the family. Altogether, it must be confessed, he is somewhat of a nuisance about this time.

It does not last long, though. He falls in love in a little while, and that soon takes the bounce out of him. I notice his boots are much too small for him now, and his hair is fearfully and wonderfully arranged. He reads poetry more than he used, and he keeps a rhyming dictionary in his bedroom. Every morning Emily Jane finds scraps of torn-up paper on the floor and reads thereon of “cruel hearts and love’s deep darts,” of “beauteous eyes and lovers’ sighs,” and much more of the old, old song that lads so love to sing and lassies love to listen to while giving their dainty heads a toss and pretending never to hear.

The course of love, however, seems not to have run smoothly, for later on he takes more walking exercise and less sleep, poor boy, than is good for him; and his face is suggestive of anything but wedding-bells and happiness ever after.

And here he seems to vanish. The little, boyish self that has grown up beside me as we walked is gone.

I am alone and the road is very dark. I stumble on, I know not how nor care, for the way seems leading nowhere, and there is no light to guide.

But at last the morning comes, and I find that I have grown into myself.

Recuerdo siempre, recuerdo siempre,

En los días del frío noviembre,

Cómo el mirlo en la…

He olvidado el resto. Es el comienzo del primer poema que me aprendí; pues el

Oye, tilín, tilín,

El gato y el violín,

no lo anoto, por tener un carácter frívolo y carecer de las cualidades de la verdadera poesía. Cobré cuatro peniques por recitar “Recuerdo siempre”. Supe que eran cuatro peniques porque me dijeron que si los guardaba hasta ganar dos peniques más tendría seis, un argumento que, si bien innegable, no me alentó, y el dinero fue derrochado, hasta donde recuerdo, a la mañana siguiente, aunque la memoria se rehúsa a decirme en qué.

Así es Memoria; nada de lo que nos trae está completo. Es una niña testaruda; todos sus juguetes están rotos. Recuerdo que, cuando era pequeño, me caí en un enorme hoyo polvoroso, pero no tengo el más mínimo recuerdo de haber salido, y si sólo confiáramos en la memoria, me vería obligado a creer que seguiría ahí.

En otra ocasión, unos años después, me encontraba en una escena de amor sumamente interesante, pero lo único que recuerdo con claridad es que, en el momento más crítico, alguien abrió la puerta de súbito y dijo: “Emily, te buscan”, con un tono sepulcral que hacía pensar que la policía había llegado por ella. Todas las tiernas palabras que me dijo y todas las bellas cosas que yo le dije han caído por completo en el olvido.

Cuando volvemos la mirada atrás, la vida en general no es más que una ruina que se desmorona: una columna destruida ahí donde se alzaba un sólido portal; el travesaño roto de una ventana para señalar la alcoba de mi mujer; un derruido montón de piedras ennegrecidas donde alguna vez saltaron las llamas relucientes y, por encima de todo, el liquen teñido y el verdor de la hiedra que se aferra.

Porque todo se vislumbra agradable a través de la atenuante neblina del tiempo. Incluso la tristeza del pasado parece dulce. Ahora los días de la niñez nos parecen muy alegres, la búsqueda de nueces, el hula-hula y el pan de jengibre. Los desaires, los dolores de muelas y los verbos en latín se han olvidado… particularmente los verbos en latín. Nos imaginamos muy felices cuando éramos traviesos y amados, y deseamos que pudiéramos volver a amar. Jamás pensamos en las angustias, en las noches de insomnio o en la ardiente sequedad en la garganta cuando ella dijo que no podía ser nada más que una hermana… ¡como si un hombre necesitara más hermanas!

Sí, es el resplandor, no la oscuridad, lo que vemos al mirar atrás. La luz del sol no proyecta sombras sobre el pasado. El camino que hemos recorrido se extiende con belleza detrás de nosotros. No vemos las piedras afiladas. Sólo nos detenemos en las rosas junto al camino, y las fuertes zarzas que nos pican son, ante nuestra mirada distante, delicados filamentos que ondean al viento. Gracias a Dios es así: que la interminable cadena de la memoria sólo tenga gratos eslabones, que la amargura y la tristeza de hoy nos traigan sonrisas mañana.

Parece como si el lado más brillante de todo fuera también el más elevado y el mejor, de modo que cuando nuestras pequeñas vidas naufragan tras nosotros en el oscuro mar del olvido, todo lo que es más luminoso y alegre es lo último en hundirse, y permanece sobre las aguas, a la vista durante mucho tiempo, mientras los pensamientos airados y el dolor agudo quedan sepultados en lo profundo de las olas y nos dejan de inquietar.

Supongo que es ese encanto del pasado lo que lleva a los viejos a decir tantas tonterías sobre los días en que eran jóvenes. El mundo parece haber sido una especie de lugar superior en aquel tiempo, cuando las cosas eran como debían ser. Entonces los niños eran niños y las niñas eran muy diferentes. También los inviernos eran algo semejante a los inviernos, y los veranos no eran en absoluto las desgracias que nos hacen pasar hoy en día. En cuanto a las maravillosas hazañas que la gente realizaba en aquellos tiempos y los extraordinarios sucesos que ocurrían, hacen falta tres hombres fornidos para creer la mitad de ellos.

Me agrada escuchar a uno de esos viejos cuando cuenta tales cosas a un grupo de jóvenes que, él sabe, no lo pueden contradecir. Es raro que, después de un rato, no jure que cuando era niño la luna brillaba todas las noches y que lanzar toros furiosos en una manta era su deporte favorito en la escuela.

Siempre ha sido y siempre será lo mismo. Los viejos de los tiempos de nuestros abuelos cantaban una canción que llevaba exactamente la misma carga, y los jóvenes de hoy dirán peroratas y tonterías similares para agraviar a la siguiente generación. “Ay, devuélvanme los buenos tiempos de hace cincuenta años”: tal ha sido la queja desde que Adán cumplió cincuenta y un años. Vuelvan a la literatura de 1835 y hallarán a poetas y novelistas pidiendo el mismo regalo imposible, como lo hicieron los Minnesänger alemanes mucho antes de ellos, y los antiguos escritores de las Sagas nórdicas mucho antes de eso. Y por lo mismo suspiraron los primeros profetas y filósofos de la antigua Grecia. Según todos los relatos, el mundo ha ido de mal en peor desde que fue creado. Todo cuanto puedo decir es que debió ser un lugar extraordinariamente encantador la primera vez que fue abierto al público, pues aun ahora es agradable si pasas todo el tiempo posible a la luz del sol, si tomas la lluvia con buen humor.

[…]

El otro día vino a verme un amigo y de manera muy elocuente me instó a aprender un prodigioso sistema mediante el cual nunca se olvida nada. No sé por qué fue tan insistente en el tema, a menos que sea porque de vez en cuando pido prestado un paraguas y tengo la manía de salir, en medio de un juego de whist, con un sutil “¡Señor!, todo este tiempo había pensado que los tréboles eran corazones”. Sin embargo, decliné la recomendación a pesar de las ventajas que tan atractivamente me planteó. No tengo ningún deseo de recordar todo. Hay muchas cosas en la vida de los hombres que es mejor olvidar. He ahí esa ocasión, hace muchos años, en que no actuamos con tanto honor, con tanta rectitud, como quizá debimos hacerlo: esa desafortunada desviación del estricto camino de la probidad en la que alguna vez incurrimos y en la que, de manera aun más desafortunada, fuimos descubiertos, aquel acto de estupidez, de mezquindad, de equivocación. ¡Ah, bueno!, y pagamos la pena, sufrimos las exasperantes horas de vano remordimiento, la ardiente agonía de la vergüenza, quizá el desprecio de quienes amamos. Olvidemos. Sí, Padre Tiempo, retira con tus bondadosas manos esos recuerdos amargos de nuestro agobiado corazón, pues las penas siempre nos llegan con las horas y nuestra fuerza es tan limitada como el día.

No se trata de enterrar el pasado. La música de la vida caería en el silencio si se rompieran las cuerdas de la memoria. Es la maleza ponzoñosa, y no las flores, la que debería ser arrancada del jardín de Mnemosine. ¿Recuerdan “El hechizado” de Dickens?: cómo suplicaba por olvidar y, cuando su plegaria fue escuchada, cómo suplicaba otra vez por recordar. No queremos echar a todos los fantasmas, sólo a los demacrados espectros de cruel mirada de los que solemos huir. Que los fantasmas amables y benévolos nos persigan como gusten; a esos no les tememos.

¡Ay de mí!, el mundo se colma de fantasmas conforme envejecemos. No es necesario buscar en lúgubres cementerios ni dormir en fincas amuralladas para ver sus rostros sombríos y escuchar el susurro de sus ropas en la noche. Cada casa, cada habitación, cada silla que rechina tiene su propio fantasma. Acechan las cámaras vacías de nuestras vidas, se amontonan a nuestro alrededor como hojas muertas revueltas por el viento otoñal. Algunos están vivos, algunos están muertos. No lo sabemos. Alguna vez estrechamos sus manos, los amamos, reñimos con ellos, reímos con ellos, les contamos nuestros pensamientos, esperanzas y aspiraciones, como ellos nos contaban las suyas, hasta que parecía que nuestros corazones se habían unido con un lazo que desafiaría el frágil poder de la Muerte. Ahora se han ido, se han perdido para siempre. Sus ojos jamás volverán a mirar los nuestros y jamás volveremos a oír sus voces. Los vemos, tenues y sombríos, a través de las lágrimas. Tendemos con anhelo las manos hacia ellos, pero sólo son aire.

¡Fantasmas! Están con nosotros día y noche. Caminan a nuestro lado en la calle concurrida, bajo el resplandor del sol. Se sientan con nosotros en la casa a la hora del crepúsculo. Vemos sus caritas mirándonos desde las ventanas de la vieja escuela. Los encontramos en el bosque y en las callejuelas donde gritábamos y jugábamos de niños. ¡Escucha! ¿No oyes sus quedas risas detrás de las zarzas y sus gritos distantes a lo largo de los claros poblados de hierba? Justo allí, entre los tranquilos campos y junto al bosque, donde merodean las sombras del anochecer, serpentea la vereda donde solíamos verla a ella al caer el sol. Mírala, ahí está ahora, con el delicado vestido blanco que tan bien conocíamos, el enorme gorro que colgaba de sus manitas y su soleado cabello castaño, todo enmarañado. ¡A ocho mil kilómetros de distancia! ¡Ha muerto, por lo que sabemos! ¿Y qué? Ahora está junto a nosotros y podemos ver sus ojos sonrientes y escuchar su voz. Desaparecerá en los escalones de la cerca junto al bosque y nos quedaremos solos; las sombras se arrastrarán por los campos y el viento nocturno se llevará los lamentos del pasado. ¡Fantasmas! Siempre estarán con nosotros, siempre estarán mientras el triste y viejo mundo siga resonando con el sollozo de los largos adioses, mientras los crueles barcos se alejen navegando los inmensos mares y la tierra fría extienda su verdor con pesadez sobre los corazones de quienes amamos.

[…]

La memoria es una extraña invocadora de fantasmas. Como una casa embrujada, sus paredes en todo momento propagan los ecos de pies invisibles. Por las ventanas rotas miramos las sombras escurridizas de los muertos, y las sombras más tristes son aquellas de nuestro propio ser que ha muerto.

Ah, esos rostros jóvenes y brillantes, tan llenos de verdad y honor, de pensamientos puros y buenos, de nobles anhelos, ¡cómo nos reprochan al mirarnos con sus ojos profundos y claros!

Pobres muchachos, me temo que tienen buenas razones para sufrir. Las mentiras, la malicia y el recelo se han arrastrado a nuestro corazón desde antes de afeitarnos… y pretendíamos ser tan grandiosos y buenos. Es bueno que no podamos ver el futuro. Muy pocos muchachos de catorce años se sentirían orgullosos de sí mismos a los cuarenta.

A veces me gusta sentarme a platicar con aquel chico raro que era yo hace mucho tiempo. Creo que a él también le agrada, pues muy a menudo viene al anochecer, cuando estoy solo con mi pipa, escuchando el susurro de las llamas. Veo su carita solemne, mirándome entre el fragante humo que sube flotando; le sonrío y él me sonríe también, pero la suya es una sonrisa grave, anticuada. Hablamos de los viejos tiempos. De vez en cuando me toma de la mano y nos deslizamos entre las negras rejillas de la chimenea y bajamos por las oscuras cuevas que refulgen hasta la tierra que se extiende tras la luz del fuego. Ahí hallamos los días del pasado y los recorremos juntos. Mientras caminamos, me cuenta todo cuanto piensa y siente. A veces me río de él, pero al siguiente instante me arrepiento, pues adopta un semblante tan serio que me avergüenzo de mi frivolidad. Eso, además, no es mostrar el debido respeto a alguien mucho mayor que yo, a ese que era yo mucho antes de que me volviera quien soy.

Al principio no hablamos mucho, sino que nos miramos; yo bajo la mirada hacia su cabello ondulado y su corbatita azul, él me mira de soslayo mientras trota. Por algún motivo imagino que esos ojos tímidos y redondos no me aprueban del todo, y exhala un breve suspiro, como si estuviera decepcionado. Pero después de un rato su timidez desaparece y comienza a platicar. Me cuenta sus relatos de hadas favoritos, hasta seis veces, y que tiene un cuyo, y que papá dice que los cuentos de hadas no son reales; ¿no es una pena? Porque le gustaría ser caballero para luchar contra un dragón y casarse con una bella princesa. Pero al cumplir siete años adopta una visión más práctica de la vida, pues de grande preferiría ser gabarrero y ganar mucho dinero. Quizá eso se debe a que se ha enamorado, justo en ese tiempo, de la damita de la lechería, que tiene seis años. (¡Dios bendiga sus piececitos bailarines, cualquiera que sea su tamaño ahora!). Debe de tenerle mucho cariño, pues un día le regala su mayor tesoro: una enorme navaja con cuatro hojas oxidadas y un sacacorchos, el cual tiene la misteriosa manía de salirse para clavarse en la pierna de su dueño. Ella es una pequeña cariñosa, le echa los brazos al cuello y lo besa por el regalo, allí mismo, afuera de la tienda. Pero el mundo estúpido (en la persona del niño del emporio de cigarros que está al lado) se burla de esas muestras de amor. Es por eso que mi joven amigo se dispone muy propiamente a golpear la cabeza del niño del emporio de cigarros, pero falla en su intento y el niño del emporio de cigarros golpea la cabeza de él.

Luego llega la vida escolar, con sus pequeñas y amargas tristezas, sus gritos de júbilo, sus felices jolgorios y sus lágrimas cálidas que caen sobre las horribles gramáticas de latín y los viejos cuadernos tontos. Es en la escuela donde queda herido de por vida, al tratar, como firmemente lo creo, de pronunciar el alemán; es ahí, también, donde aprende la importancia que la nación francesa da a las plumas, a la tinta y al papel. “¿Tiene plumas, tinta y papel?” es la primera pregunta que le hace un francés a otro cuando se conocen.

[…]

De modo que en la adquisición de un conocimiento más o menos inútil, que pronto será felizmente olvidado, se va la infancia. La escuela de ladrillos rojos se esfuma de la vista y tomamos el camino del mundo. Entonces mi amiguito ya no es pequeño. A la chaqueta le ha brotado un faldón. La gorra maltrecha, que tan bien combinaba con el pañuelo de bolsillo, el vaso para beber y el arma de ataque, se ha vuelto alta y lustrosa, y en lugar del lápiz en la boca lleva un cigarrillo, cuyo humo le molesta porque le sube hasta la nariz. Poco después prueba un puro, por ser más elegante: un enorme habano negro. Parece que no le cae muy bien, pues más tarde lo encuentro sentado en un balde de la cocina trasera, jurando solemnemente no volver a fumar.

Ahora el bigote se le empieza a notar casi a simple vista, con lo cual se aficiona de inmediato al brandy con soda y se cree un hombre. Habla de “dos a uno contra el favorito”, se refiere a las actrices como “la chiquilla Emmy”, “Kate” y “la Beba”, y murmura acerca de lo que “la otra noche perdió en los naipes”, con un estilo que implica que ha derrochado miles, aunque, para hacerle justicia, muy probablemente la cantidad verdadera sea un chelín con dos peniques. Si veo bien —pues en esta tierra de los recuerdos permanece el ocaso—, también lleva un monóculo en el ojo y tropieza con todo.

Sus amigas, con las que mantiene relaciones muy problemáticas, rezan por él (¡benditos sean sus dulces corazones!) y presagian juicios en Old Bailey y cabestrillos como único resultado posible de esa disipación tan insensata; la predicción de su primer maestro escolar, quien dijo que terminaría mal, adquiere las proporciones de una inspirada profecía.

A esa edad siente un desprecio señorial por el sexo opuesto, tiene una opinión descaradamente positiva de él mismo y en sociedad trata de manera condescendiente a los ancianos que son amigos de la familia. En general, hay que confesarlo, en aquella época es algo irritante.

Pero eso no dura mucho. Al poco tiempo se enamora, lo cual pronto le quita el vigor. Advierto que ahora sus botas son demasiado pequeñas para él y que se arregla el cabello con sumo y estupendo cuidado. Lee más poesía que antes y guarda un diccionario de rimas en su habitación. Todas las mañanas, Emily Jane encuentra en el piso trozos de papel en los que se lee sobre “corazones crueles y profundos dardos de amor”, sobre “bellos ojos y suspiros de amantes” y aun más sobre canciones muy, muy viejas que los muchachos adoran cantar y las muchachas adoran escuchar mientras sacuden sus delicadas cabezas, fingiendo no escuchar.

Sin embargo, el curso del amor no parece haber transcurrido sin contratiempos, pues, pobre muchacho, más tarde se ejercita dando paseos más largos y duerme menos de lo que le conviene; en su rostro se percibe cualquier cosa salvo campanas de boda y felicidad por siempre.

En este punto parece desvanecerse. El pequeño yo de la infancia que creció a mi lado mientras caminábamos ha partido.

Estoy solo y el camino es muy oscuro. Sigo tropezando, no sé cómo ni me importa, pues este rumbo parece no llevar a ningún lado y no hay luz alguna que me guíe.

Pero al fin llega la mañana y descubro que he crecido hasta ser quien soy.

Alejandro Nájera (Ciudad de México), docente y traductor. Es maestro en Letras Modernas por la Facultad de Filosofía y Letras de la UNAM. Ha publicado reseñas, ensayos, relatos y traducciones en medios como La palabra y el hombre, Letralia. Tierra de Letras, Revista Almiar, Revista Corónica, Punto en línea, Centro Onelio y La nave. En 2018, ganó el “II Concurso Internacional de Escritura Creativa Skribalia” con el relato “La textura del tiempo”. En 2023, concluyó el Diplomado en Traducción Literaria y Humanística en la Asociación Mexicana de Traductores Literarios, de la que es miembro aspirante. También en 2023, su relato “La película finlandesa” fue elegido cuento ganador para conformar la antología del “4to Concurso Internacional de Narrativa Fundación la Balandra”. Es creador del blog La página impresa, donde publica traducciones de poesía en lengua inglesa sin ánimo de lucro y sin más intención que compartir poemas que le gustan.