Miss Brill

Traducción del inglés por los estudiantes del Diplomado en Traducción Literaria de la Universidad Central.

Texto original de Katherine Mansfield

Edición por Daniela Arias

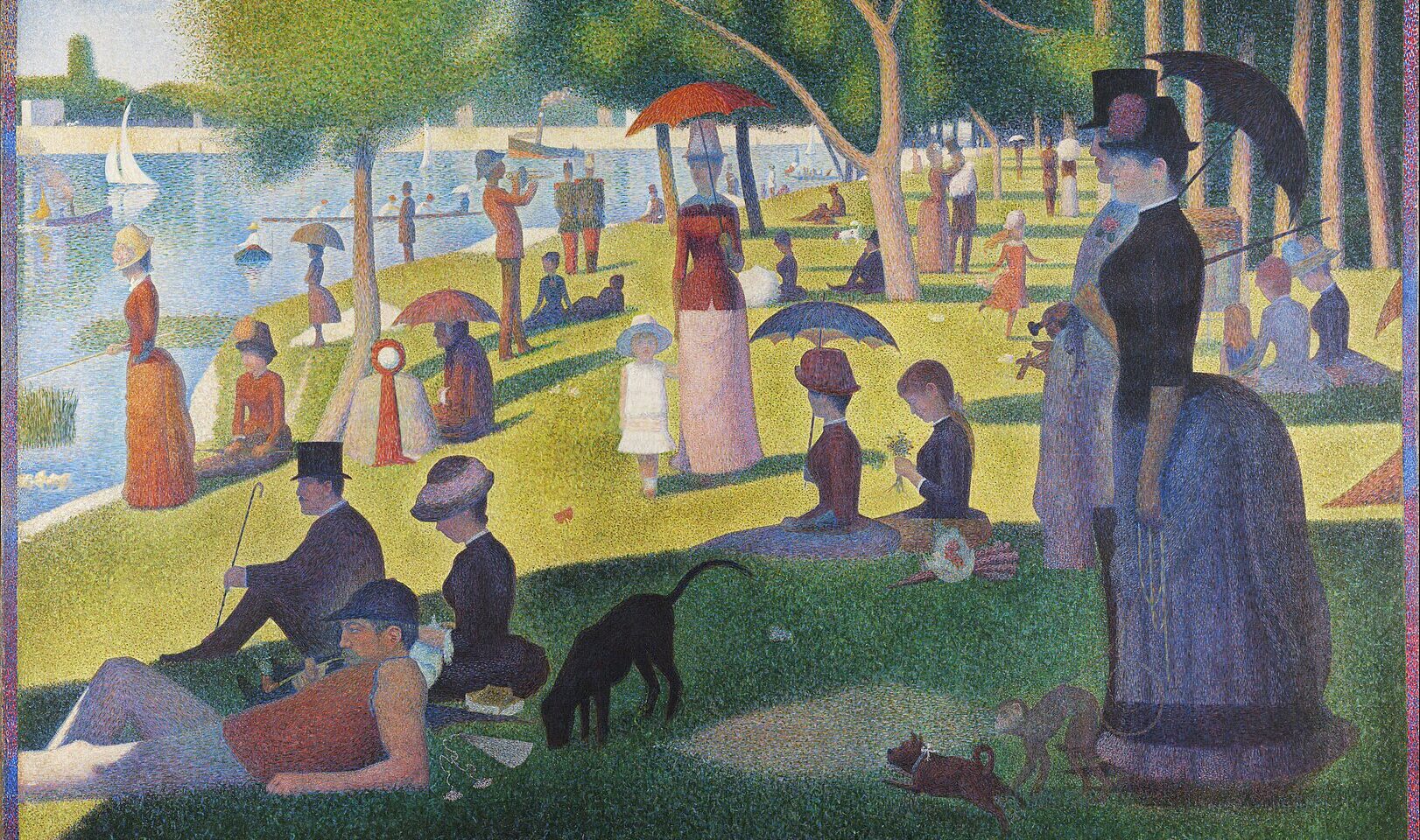

Imagen: «A Sunday on La Grande Jatte» de Georges Seurat

Aunque estaba muy iluminado —el cielo azul espolvoreado con oro y grandes manchas de luz como vino blanco salpicado sobre los Jardins Publiques— Miss Brill estaba complacida de haberse decidido por la piel. El aire estaba inmóvil, pero cuando abrías la boca había un leve frío, como el frío de un vaso de agua helada antes de darle un sorbo, y de vez en cuando una hoja caía sin rumbo —de ningún lugar, del cielo—. Miss Brill alzó la mano y tocó la piel. ¡Cosita adorada! Era agradable sentirla de nuevo. Lo había sacado de su caja esa tarde, le había sacudido la naftalina, dado una buena cepillada y lo había frotado hasta devolverle la vida a esos ojitos apagados. «¿Qué me ha estado pasando?», dijeron los ojitos tristes. ¡Oh, qué dulce era verlos centellearle de nuevo desde el edredón rojo!… Pero la nariz, de algún material negro, no era para nada firme. Debió haberse golpeado de algún modo. No importa: un toquecito de lacre negro cuando llegara el momento, cuando fuera absolutamente necesario.… ¡Pequeño pícaro! Sí, en realidad sentía que lo era. Un pequeño pícaro que se mordía la cola justo al lado de la oreja izquierda. Podría habérselo quitado y haberlo posado en su regazo para acariciarlo. Sentía un cosquilleo en las manos y los brazos, aunque suponía que era por caminar. Y cuando respiraba, algo ligero y triste —no, no exactamente triste— algo suave parecía moverse en su pecho.

Había mucha gente esa tarde, mucha más que el domingo anterior. Y la banda sonaba más fuerte y más alegre. Eso era porque la Temporada había comenzado. Pues aunque la banda tocaba todos los domingos del año, fuera de temporada nunca era lo mismo. Era como si alguien tocara solo para que la familia escuchara; no importaba cómo sonaba si no había extraños presentes. ¿Acaso no usaba también el director una levita nueva? Estaba segura de que era nueva. Rascaba con el pie y agitaba los brazos como un gallo a punto de cantar, y los músicos sentados en la rotonda verde desinflaban sus mejillas y clavaban la mirada en la música. Ahí venía un poquito de flauta —¡Muy bonita!— una pequeña cadena de gotas brillantes. Estaba segura de que se repetiría. Así fue; levantó la cabeza y sonrió.

Solo dos personas compartían su asiento «especial»: un refinado anciano con abrigo de terciopelo, sus manos entrelazadas sobre un gran bastón tallado, y una anciana corpulenta, sentada erguida, con una madeja sobre su delantal bordado. No hablaban. Era decepcionante, pues Miss Brill siempre aguardaba la conversación. Se había convertido en toda una experta, así lo creía, en escuchar como si no escuchara, en sentarse en la vida de otras personas solo por un minuto mientras hablaban a su alrededor.

Echó un vistazo, de reojo, a la pareja de ancianos. Tal vez se irían pronto. El domingo anterior tampoco había sido tan interesante como de costumbre. Un inglés y su esposa, él con un espantoso sombrero Panamá y ella con botines de abotonar. Y ella no había parado de hablar de que debía usar anteojos; sabía que los necesitaba; pero no serviría de nada conseguirlos; seguramente se romperían y nunca se mantendrían en su lugar. Y él había sido tan paciente. Le había sugerido todo: montura de oro, del tipo que se curva en las orejas, con pequeños soportes en del puente. No, nada la satisfacía. «¡Se me van a estar resbalando de la nariz!». Miss Brill había querido zarandearla.

Los ancianos permanecían sentados en la banca, quietos como estatuas. No importaba, siempre había una multitud para observar. De aquí para allá, frente a las jardineras y la rotonda de la banda, las parejas y los grupos desfilaban, se detenían a conversar, a saludar, a comprarle un ramo de flores al viejo mendigo que había sujetado su charola a las rejas. Niños pequeños corrían entre ellos, abalanzándose y riendo; hombrecitos con grandes corbatines blancos bajo la barbilla, mujercitas, muñequitas francesas, vestidas de terciopelo y encaje. Y algunas veces un chiquitín tambaleante venía de repente al claro balanceándose bajo los árboles, se detenía, se quedaba mirando y de repente «plop», se sentaba, hasta que su pequeña madre, los pies en alto, como una gallina joven, se apresuraba a su rescate regañándolo. Otras personas se sentaban en las bancas y en las sillas verdes, pero casi siempre eran las mismas, domingo tras domingo, y —Miss Brill lo había notado a menudo— la mayoría tenía algo curioso. Eran extraños, silenciosos, casi todos viejos y, por la forma en la que fijaban la mirada, parecía como si acabaran de salir de pequeñas habitaciones oscuras o incluso, ¡incluso armarios!

Detrás de la rotonda, los árboles esbeltos con hojas amarillas a punto de caer, y a través de ellos apenas una línea de mar, y más allá el cielo azul con nubes veteadas de oro.

¡Pam-pam-pam param-pam! ¡Param-pam! ¡Pam parim-pam pam pa!, tocó la banda.

Dos jovencitas de rojo pasaron y dos soldados jóvenes de azul se encontraron con ellas, y rieron y se emparejaron y se fueron de gancho. Dos campesinas con graciosos sombreros de paja pasaron, solemnemente, guiando hermosos burros de color humo. Una fría y pálida monja pasó con prisa. Una hermosa mujer apareció y dejó caer su ramo de violetas, y un niño pequeño la persiguió para entregárselas, y ella las tomó y las arrojó lejos, como si estuvieran envenenadas. ¡Válgame, Dios! ¡Miss Brill no sabía si sentir admiración o no! Y ahora un tocado de armiño y un caballero de gris se encontraron justo frente a ella. Él era alto, rígido, digno, y ella estaba usando el tocado de armiño que había comprado cuando su cabello era amarillo. Ahora todo, su cabello, su cara, incluso sus ojos, era del mismo color que el armiño andrajoso, y su mano, en su guante limpio, alzada para rozar sus labios, era una diminuta pata amarillenta. Oh, ella estaba tan complacida de verlo, ¡encantada! Prefería pensar que iban a encontrarse esa tarde. Describió dónde había estado: en todas partes, aquí, allá, junto al mar. El día era tan encantador, ¿no estaba de acuerdo? Y ¿no le gustaría, tal vez?… Pero él negó con la cabeza, prendió un cigarrillo, exhaló lentamente una profunda bocanada en el rostro de ella, y, pese a que ella aún seguía hablando y riendo, arrojó el fósforo y se marchó. El tocado de armiño estaba solo; sonrió más radiante que nunca. Pero incluso la banda parecía saber lo que ella estaba sintiendo y tocó más suave, tocó con ternura, y el golpeteo del tambor, «¡Bruto! ¡Bruto!», una y otra vez. ¿Qué haría ella? ¿Qué iba a ocurrir ahora? Pero mientras Miss Brill se preguntaba esto, el tocado de armiño se giró, levantó la mano como si hubiera visto a alguien más, mucho más agradable, a escasos pasos, y se alejó con andar ligero. Y la banda volvió a cambiar y tocó más deprisa, más alegre que nunca, y la pareja de ancianos en el asiento de Miss Brill se levantó y se marchó, y ese anciano curioso con bigotes largos avanzaba cojeando al ritmo de la música y casi lo chocan cuatro chicas que caminaban una junto a la otra.

¡Oh, qué fascinante era! ¡Cómo lo disfrutaba! ¡Cómo le encantaba sentarse allí, a observarlo todo! Era como una obra. Era exactamente como una obra. ¿Quién podría creer que el cielo en el fondo no estaba pintado? Pero no fue sino hasta que un pequeño perro café pasó trotando solemne y luego se alejó trotando lentamente, como un pequeño perro de «teatro», un pequeño perro al que habían drogado, que Miss Brill descubrió qué era lo que lo hacía tan emocionante. Todos estaban en el escenario. No solo eran la audiencia, no solo observaban; estaban actuando. Incluso ella tenía un papel y venía cada domingo. Sin duda alguien habría notado si ella no hubiera estado allí; después de todo, era parte de la función. ¡Qué extraño que nunca antes lo hubiera pensado de esa manera! Y aun así eso explicaba por qué ponía tanto empeño en salir de casa exactamente a la misma hora cada semana —para no llegar tarde a la función— y explicaba también por qué tenía una sensación tan extraña y tímida al decirle a sus estudiantes de inglés cómo pasaba las tardes de los domingos. ¡No era de extrañar! Miss Brill casi suelta una carcajada. Estaba en el escenario. Pensó en el caballero anciano e inválido al que le leía el periódico cuatro tardes a la semana mientras él dormía en el jardín. Ella ya se había acostumbrado bastante a la frágil cabeza en la almohada de algodón, los ojos hundidos, la boca abierta y la nariz respingada. Si él hubiera estado muerto ella podría no haberlo notado en semanas; no le habría importado. ¡Pero de repente él supo que quien le estaba leyendo el periódico era una actriz! «¡Una actriz!». La vieja cabeza levantada; dos puntos de luz titilaron en los ojos envejecidos. «Una actriz, ¿eh?». Y Miss Brill alisó el periódico como si fuera el manuscrito con su parte y respondió gentilmente: «Sí, he sido actriz por mucho tiempo».

La banda había tomado un descanso. Ahora empezaban de nuevo. Y lo que tocaban era cálido, soleado, aunque se sentía apenas un ligero escalofrío —un algo, ¿qué era? —no tristeza— no, no tristeza— un algo que te hacía querer cantar. La melodía ascendía, ascendía, la luz brillaba; y a Miss Brill le pareció que en un instante todos ellos, toda la compañía, empezarían a cantar. Los jóvenes, los que reían y se movían juntos, empezarían, y las voces de los hombres, muy decididas y valientes, se les unirían. Y entonces ella también, ella también, y los otros en las bancas, se unirían con una especie de acompañamiento, algo grave, que escasamente ascendía o descendía, algo muy hermoso, conmovedor. . . . Y los ojos de Miss Brill se llenaron de lágrimas y observó sonriendo a todos los miembros de la compañía. Sí, entendemos, entendemos, pensó —aunque ella no sabía qué era lo que ellos entendían—.

Justo en ese momento llegaron un chico y una chica y se sentaron donde había estado la pareja de ancianos. Estaban bellamente vestidos; estaban enamorados. El héroe y la heroína, por supuesto, recién llegados del yate del padre del chico. Y aún cantando sin voz , aún con una sonrisa trémula, Miss Brill se dispuso a escuchar.

—No, ahora no —dijo la chica—. Aquí no, no puedo.

—Pero, ¿por qué? ¿Por ese estúpido vejestorio de allá? —preguntó el chico—. ¿Al fin y al cabo para qué viene? ¿Quién la quiere? ¿Por qué no deja esa cara tan vieja y ridícula en casa?

—Es la pi-piel lo que me causa tanta gracia —dijo la chica mientras soltaba una risita—. Es igualita a un merlán frito.

—¡Ah, ya me tienes harto! –dijo el chico susurrando con enojo. Luego añadió—: dime, ma petite chère…

—No, aquí no —dijo la chica—. Todavía no.

De camino a casa solía comprar una rebanada de pastel de miel en la panadería. Ese era el gusto que se daba los domingos. A veces había una almendra en su rebanada, a veces no. Esto marcaba una gran diferencia. Si había una almendra era como llevarse a casa un regalo diminuto —una sorpresa— algo que bien podría no haber estado allí. Los domingos de almendra se apresuraba y encendía el fósforo para la tetera de un modo bastante vivaz.

Pero hoy no se detuvo en la panadería. Subió las escaleras, fue a la pequeña habitación oscura —la habitación parecida a un armario— y se sentó sobre el edredón rojo. Permaneció sentada allí durante mucho tiempo. La caja de donde había salido la piel estaba sobre la cama. Se desabrochó el cuello deprisa; deprisa, sin mirar, lo colocó adentro. Pero cuando puso la tapa creyó escuchar que algo lloraba.

Although it was so brilliantly fine – the blue sky powdered with gold and great spots of light like white wine splashed over the Jardins Publiques – Miss Brill was glad that she had decided on her fur. The air was motionless, but when you opened your mouth there was just a faint chill, like a chill from a glass of iced water before you sip, and now and again a leaf came drifting – from nowhere, from the sky. Miss Brill put up her hand and touched her fur. Dear little thing! It was nice to feel it again. She had taken it out of its box that afternoon, shaken out the moth-powder, given it a good brush, and rubbed the life back into the dim little eyes. ‘What has been happening to me?’ said the sad little eyes. Oh, how sweet it was to see them snap at her again from the red eiderdown! . . . But the nose, which was of some black composition, wasn’t at all firm. It must have had a knock, somehow. Never mind – a little dab of black sealing-wax when the time came – when it was absolutely necessary. . . . Little rogue! Yes, she really felt like that about it. Little rogue biting its tail just by her left ear. She could have taken it off and laid it on her lap and stroked it. She felt a tingling in her hands and arms, but that came from walking, she supposed. And when she breathed, something light and sad – no, not sad, exactly – something gentle seemed to move in her bosom.

There were a number of people out this afternoon, far more than last Sunday. And the band sounded louder and gayer. That was because the Season had begun. For although the band played all the year round on Sundays, out of season it was never the same. It was like some one playing with only the family to listen; it didn’t care how it played if there weren’t any strangers present. Wasn’t the conductor wearing a new coat, too? She was sure it was new. He scraped with his foot and flapped his arms like a rooster about to crow, and the bandsmen sitting in the green rotunda blew out their cheeks and glared at the music. Now there came a little ‘flutey’ bit – very pretty! – a little chain of bright drops. She was sure it would be repeated. It was; she lifted her head and smiled.

Only two people shared her ‘special’ seat: a fine old man in a velvet coat, his hands clasped over a huge carved walking-stick, and a big old woman, sitting upright, with a roll of knitting on her embroidered apron. They did not speak. This was disappointing, for Miss Brill always looked forward to the conversation. She had become really quite expert, she thought, at listening as though she didn’t listen, at sitting in other people’s lives just for a minute while they talked round her.

She glanced, sideways, at the old couple. Perhaps they would go soon. Last Sunday, too, hadn’t been as interesting as usual. An Englishman and his wife, he wearing a dreadful Panama hat and she button boots. And she’d gone on the whole time about how she ought to wear spectacles; she knew she needed them; but that it was no good getting any; they’d be sure to break and they’d never keep on. And he’d been so patient. He’d suggested everything – gold rims, the kind that curved round your ears, little pads inside the bridge. No, nothing would please her. ‘They’ll always be sliding down my nose!’ Miss Brill had wanted to shake her.

The old people sat on the bench, still as statues. Never mind, there was always the crowd to watch. To and fro, in front of the flowerbeds and the band rotunda, the couples and groups paraded, stopped to talk, to greet, to buy a handful of flowers from the old beggar who had his tray fixed to the railings. Little children ran among them, swooping and laughing; little boys with big white silk bows under their chins, little girls, little French dolls, dressed up in velvet and lace. And sometimes a tiny staggerer came suddenly rocking into the open from under the trees, stopped, stared, as suddenly sat down ‘flop’, until its small high-stepping mother, like a young hen, rushed scolding to its rescue. Other people sat on the benches and green chairs, but they were nearly always the same, Sunday after Sunday, and – Miss Brill had often noticed – there was something funny about nearly all of them. They were odd, silent, nearly all old, and from the way they stared they looked as though they’d just come from dark little rooms or even – even cupboards!

Behind the rotunda the slender trees with yellow leaves down drooping, and through them just a line of sea, and beyond the blue sky with gold-veined clouds.

Tum-tum-tum tiddle-um! tiddle-um! tum tiddley-um tum ta! blew the band.

Two young girls in red came by and two young soldiers in blue met them, and they laughed and paired and went off arm-in-arm. Two peasant women with funny straw hats passed, gravely, leading beautiful smoke-coloured donkeys. A cold, pale nun hurried by. A beautiful woman came along and dropped her bunch of violets, and a little boy ran after to hand them to her, and she took them and threw them away as if they’d been poisoned. Dear me! Miss Brill didn’t know whether to admire that or not! And now an ermine toque and a gentleman in grey met just in front of her. He was tall, stiff, dignified, and she was wearing the ermine toque she’d bought when her hair was yellow. Now everything, her hair, her face, even her eyes, was the same colour as the shabby ermine, and her hand, in its cleaned glove, lifted to dab her lips, was a tiny yellowish paw. Oh, she was so pleased to see him – delighted! She rather thought they were going to meet that afternoon. She described where she’d been – everywhere, here, there, along by the sea. The day was so charming – didn’t he agree? And wouldn’t he, perhaps? . . . But he shook his head, lighted a cigarette, slowly breathed a great deep puff into her face, and, even while she was still talking and laughing, flicked the match away and walked on. The ermine toque was alone; she smiled more brightly than ever. But even the band seemed to know what she was feeling and played more softly, played tenderly, and the drum beat, ‘The Brute! The Brute!’ over and over. What would she do? What was going to happen now? But as Miss Brill wondered, the ermine toque turned, raised her hand as though she’d seen some one else, much nicer, just over there, and pattered away. And the band changed again and played more quickly, more gaily than ever, and the old couple on Miss Brill’s seat got up and marched away, and such a funny old man with long whiskers hobbled along in time to the music and was nearly knocked over by four girls walking abreast.

Oh, how fascinating it was! How she enjoyed it! How she loved sitting here, watching it all! It was like a play. It was exactly like a play. Who could believe the sky at the back wasn’t painted? But it wasn’t till a little brown dog trotted on solemn and then slowly trotted off, like a little ‘theatre’ dog, a little dog that had been drugged, that Miss Brill discovered what it was that made it so exciting. They were all on the stage. They weren’t only the audience, not only looking on; they were acting. Even she had a part and came every Sunday. No doubt somebody would have noticed if she hadn’t been there; she was part of the performance after all. How strange she’d never thought of it like that before! And yet it explained why she made such a point of starting from home at just the same time each week – so as not to be late for the performance – and it also explained why she had quite a queer, shy feeling at telling her English pupils how she spent her Sunday afternoons. No wonder! Miss Brill nearly laughed out loud. She was on the stage. She thought of the old invalid gentleman to whom she read the newspaper four afternoons a week while he slept in the garden. She had got quite used to the frail head on the cotton pillow, the hollowed eyes, the open mouth and the high pinched nose. If he’d been dead she mightn’t have noticed for weeks; she wouldn’t have minded. But suddenly he knew he was having the paper read to him by an actress! ‘An actress!’ The old head lifted; two points of light quivered in the old eyes. ‘An actress – are ye?’ And Miss Brill smoothed the newspaper as though it were the manuscript of her part and said gently: ‘Yes, I have been an actress for a long time.’

The band had been having a rest. Now they started again. And what they played was warm, sunny, yet there was just a faint chill – a something what was it? – not sadness – no, not sadness – a something that made you want to sing. The tune lifted, lifted, the light shone; and it seemed to Miss Brill that in another moment all of them, all the whole company, would begin singing. The young ones, the laughing ones who were moving together, they would begin, and the men’s voices, very resolute and brave, would join them. And then she too, she too, and the others on the benches – they would come in with a kind of accompaniment – something low, that scarcely rose or fell, something so beautiful – moving. . . . And Miss Brill’s eyes filled with tears and she looked smiling at all the other members of the company. Yes, we understand, we understand, she thought – though what they understood she didn’t know.

Just at that moment a boy and a girl came and sat down where the old couple had been. They were beautifully dressed; they were in love. The hero and heroine, of course, just, arrived from his father’s yacht. And still soundlessly singing, still with that trembling smile, Miss Brill prepared to listen.

‘No, not now,’ said the girl.’ Not here, I can’t.’

‘But why? Because of that stupid old thing at the end there?’ asked the boy. ‘Why does she come here at all – who wants her? Why doesn’t she keep her silly old mug at home?’

‘It’s her fu-fur which is so funny,’ giggled the girl. ‘It’s exactly like a fried whiting.’

‘Ah, be off with you!’ said the boy in an angry whisper. Then: ‘Tell me, ma petite chère –’

‘No, not here,’ said the girl. ‘Not yet.’

On her way home she usually bought a slice of honey-cake at the baker’s. It was her Sunday treat. Sometimes there was an almond in her slice, sometimes not. It made a great difference. If there was an almond it was like carrying home a tiny present – a surprise – something that might very well not have been there. She hurried on the almond Sundays and struck the match for the kettle in quite a dashing way.

But to-day she passed the baker’s by, climbed the stairs, went into the little dark room – her room like a cupboard – and sat down on the red eiderdown. She sat there for a long time. The box that the fur came out of was on the bed. She unclasped the necklet quickly; quickly, without looking, laid it inside. But when she put the lid on she thought she heard something crying.

Although it was so brilliantly fine – the blue sky powdered with gold and great spots of light like white wine splashed over the Jardins Publiques – Miss Brill was glad that she had decided on her fur. The air was motionless, but when you opened your mouth there was just a faint chill, like a chill from a glass of iced water before you sip, and now and again a leaf came drifting – from nowhere, from the sky. Miss Brill put up her hand and touched her fur. Dear little thing! It was nice to feel it again. She had taken it out of its box that afternoon, shaken out the moth-powder, given it a good brush, and rubbed the life back into the dim little eyes. ‘What has been happening to me?’ said the sad little eyes. Oh, how sweet it was to see them snap at her again from the red eiderdown! . . . But the nose, which was of some black composition, wasn’t at all firm. It must have had a knock, somehow. Never mind – a little dab of black sealing-wax when the time came – when it was absolutely necessary. . . . Little rogue! Yes, she really felt like that about it. Little rogue biting its tail just by her left ear. She could have taken it off and laid it on her lap and stroked it. She felt a tingling in her hands and arms, but that came from walking, she supposed. And when she breathed, something light and sad – no, not sad, exactly – something gentle seemed to move in her bosom.

There were a number of people out this afternoon, far more than last Sunday. And the band sounded louder and gayer. That was because the Season had begun. For although the band played all the year round on Sundays, out of season it was never the same. It was like some one playing with only the family to listen; it didn’t care how it played if there weren’t any strangers present. Wasn’t the conductor wearing a new coat, too? She was sure it was new. He scraped with his foot and flapped his arms like a rooster about to crow, and the bandsmen sitting in the green rotunda blew out their cheeks and glared at the music. Now there came a little ‘flutey’ bit – very pretty! – a little chain of bright drops. She was sure it would be repeated. It was; she lifted her head and smiled.

Only two people shared her ‘special’ seat: a fine old man in a velvet coat, his hands clasped over a huge carved walking-stick, and a big old woman, sitting upright, with a roll of knitting on her embroidered apron. They did not speak. This was disappointing, for Miss Brill always looked forward to the conversation. She had become really quite expert, she thought, at listening as though she didn’t listen, at sitting in other people’s lives just for a minute while they talked round her.

She glanced, sideways, at the old couple. Perhaps they would go soon. Last Sunday, too, hadn’t been as interesting as usual. An Englishman and his wife, he wearing a dreadful Panama hat and she button boots. And she’d gone on the whole time about how she ought to wear spectacles; she knew she needed them; but that it was no good getting any; they’d be sure to break and they’d never keep on. And he’d been so patient. He’d suggested everything – gold rims, the kind that curved round your ears, little pads inside the bridge. No, nothing would please her. ‘They’ll always be sliding down my nose!’ Miss Brill had wanted to shake her.

The old people sat on the bench, still as statues. Never mind, there was always the crowd to watch. To and fro, in front of the flowerbeds and the band rotunda, the couples and groups paraded, stopped to talk, to greet, to buy a handful of flowers from the old beggar who had his tray fixed to the railings. Little children ran among them, swooping and laughing; little boys with big white silk bows under their chins, little girls, little French dolls, dressed up in velvet and lace. And sometimes a tiny staggerer came suddenly rocking into the open from under the trees, stopped, stared, as suddenly sat down ‘flop’, until its small high-stepping mother, like a young hen, rushed scolding to its rescue. Other people sat on the benches and green chairs, but they were nearly always the same, Sunday after Sunday, and – Miss Brill had often noticed – there was something funny about nearly all of them. They were odd, silent, nearly all old, and from the way they stared they looked as though they’d just come from dark little rooms or even – even cupboards!

Behind the rotunda the slender trees with yellow leaves down drooping, and through them just a line of sea, and beyond the blue sky with gold-veined clouds.

Tum-tum-tum tiddle-um! tiddle-um! tum tiddley-um tum ta! blew the band.

Two young girls in red came by and two young soldiers in blue met them, and they laughed and paired and went off arm-in-arm. Two peasant women with funny straw hats passed, gravely, leading beautiful smoke-coloured donkeys. A cold, pale nun hurried by. A beautiful woman came along and dropped her bunch of violets, and a little boy ran after to hand them to her, and she took them and threw them away as if they’d been poisoned. Dear me! Miss Brill didn’t know whether to admire that or not! And now an ermine toque and a gentleman in grey met just in front of her. He was tall, stiff, dignified, and she was wearing the ermine toque she’d bought when her hair was yellow. Now everything, her hair, her face, even her eyes, was the same colour as the shabby ermine, and her hand, in its cleaned glove, lifted to dab her lips, was a tiny yellowish paw. Oh, she was so pleased to see him – delighted! She rather thought they were going to meet that afternoon. She described where she’d been – everywhere, here, there, along by the sea. The day was so charming – didn’t he agree? And wouldn’t he, perhaps? . . . But he shook his head, lighted a cigarette, slowly breathed a great deep puff into her face, and, even while she was still talking and laughing, flicked the match away and walked on. The ermine toque was alone; she smiled more brightly than ever. But even the band seemed to know what she was feeling and played more softly, played tenderly, and the drum beat, ‘The Brute! The Brute!’ over and over. What would she do? What was going to happen now? But as Miss Brill wondered, the ermine toque turned, raised her hand as though she’d seen some one else, much nicer, just over there, and pattered away. And the band changed again and played more quickly, more gaily than ever, and the old couple on Miss Brill’s seat got up and marched away, and such a funny old man with long whiskers hobbled along in time to the music and was nearly knocked over by four girls walking abreast.

Oh, how fascinating it was! How she enjoyed it! How she loved sitting here, watching it all! It was like a play. It was exactly like a play. Who could believe the sky at the back wasn’t painted? But it wasn’t till a little brown dog trotted on solemn and then slowly trotted off, like a little ‘theatre’ dog, a little dog that had been drugged, that Miss Brill discovered what it was that made it so exciting. They were all on the stage. They weren’t only the audience, not only looking on; they were acting. Even she had a part and came every Sunday. No doubt somebody would have noticed if she hadn’t been there; she was part of the performance after all. How strange she’d never thought of it like that before! And yet it explained why she made such a point of starting from home at just the same time each week – so as not to be late for the performance – and it also explained why she had quite a queer, shy feeling at telling her English pupils how she spent her Sunday afternoons. No wonder! Miss Brill nearly laughed out loud. She was on the stage. She thought of the old invalid gentleman to whom she read the newspaper four afternoons a week while he slept in the garden. She had got quite used to the frail head on the cotton pillow, the hollowed eyes, the open mouth and the high pinched nose. If he’d been dead she mightn’t have noticed for weeks; she wouldn’t have minded. But suddenly he knew he was having the paper read to him by an actress! ‘An actress!’ The old head lifted; two points of light quivered in the old eyes. ‘An actress – are ye?’ And Miss Brill smoothed the newspaper as though it were the manuscript of her part and said gently: ‘Yes, I have been an actress for a long time.’

The band had been having a rest. Now they started again. And what they played was warm, sunny, yet there was just a faint chill – a something what was it? – not sadness – no, not sadness – a something that made you want to sing. The tune lifted, lifted, the light shone; and it seemed to Miss Brill that in another moment all of them, all the whole company, would begin singing. The young ones, the laughing ones who were moving together, they would begin, and the men’s voices, very resolute and brave, would join them. And then she too, she too, and the others on the benches – they would come in with a kind of accompaniment – something low, that scarcely rose or fell, something so beautiful – moving. . . . And Miss Brill’s eyes filled with tears and she looked smiling at all the other members of the company. Yes, we understand, we understand, she thought – though what they understood she didn’t know.

Just at that moment a boy and a girl came and sat down where the old couple had been. They were beautifully dressed; they were in love. The hero and heroine, of course, just, arrived from his father’s yacht. And still soundlessly singing, still with that trembling smile, Miss Brill prepared to listen.

‘No, not now,’ said the girl.’ Not here, I can’t.’

‘But why? Because of that stupid old thing at the end there?’ asked the boy. ‘Why does she come here at all – who wants her? Why doesn’t she keep her silly old mug at home?’

‘It’s her fu-fur which is so funny,’ giggled the girl. ‘It’s exactly like a fried whiting.’

‘Ah, be off with you!’ said the boy in an angry whisper. Then: ‘Tell me, ma petite chère –’

‘No, not here,’ said the girl. ‘Not yet.’

On her way home she usually bought a slice of honey-cake at the baker’s. It was her Sunday treat. Sometimes there was an almond in her slice, sometimes not. It made a great difference. If there was an almond it was like carrying home a tiny present – a surprise – something that might very well not have been there. She hurried on the almond Sundays and struck the match for the kettle in quite a dashing way.

But to-day she passed the baker’s by, climbed the stairs, went into the little dark room – her room like a cupboard – and sat down on the red eiderdown. She sat there for a long time. The box that the fur came out of was on the bed. She unclasped the necklet quickly; quickly, without looking, laid it inside. But when she put the lid on she thought she heard something crying.

Aunque estaba muy iluminado —el cielo azul espolvoreado con oro y grandes manchas de luz como vino blanco salpicado sobre los Jardins Publiques— Miss Brill estaba complacida de haberse decidido por la piel. El aire estaba inmóvil, pero cuando abrías la boca había un leve frío, como el frío de un vaso de agua helada antes de darle un sorbo, y de vez en cuando una hoja caía sin rumbo —de ningún lugar, del cielo—. Miss Brill alzó la mano y tocó la piel. ¡Cosita adorada! Era agradable sentirla de nuevo. Lo había sacado de su caja esa tarde, le había sacudido la naftalina, dado una buena cepillada y lo había frotado hasta devolverle la vida a esos ojitos apagados. «¿Qué me ha estado pasando?», dijeron los ojitos tristes. ¡Oh, qué dulce era verlos centellearle de nuevo desde el edredón rojo!… Pero la nariz, de algún material negro, no era para nada firme. Debió haberse golpeado de algún modo. No importa: un toquecito de lacre negro cuando llegara el momento, cuando fuera absolutamente necesario.… ¡Pequeño pícaro! Sí, en realidad sentía que lo era. Un pequeño pícaro que se mordía la cola justo al lado de la oreja izquierda. Podría habérselo quitado y haberlo posado en su regazo para acariciarlo. Sentía un cosquilleo en las manos y los brazos, aunque suponía que era por caminar. Y cuando respiraba, algo ligero y triste —no, no exactamente triste— algo suave parecía moverse en su pecho.

Había mucha gente esa tarde, mucha más que el domingo anterior. Y la banda sonaba más fuerte y más alegre. Eso era porque la Temporada había comenzado. Pues aunque la banda tocaba todos los domingos del año, fuera de temporada nunca era lo mismo. Era como si alguien tocara solo para que la familia escuchara; no importaba cómo sonaba si no había extraños presentes. ¿Acaso no usaba también el director una levita nueva? Estaba segura de que era nueva. Rascaba con el pie y agitaba los brazos como un gallo a punto de cantar, y los músicos sentados en la rotonda verde desinflaban sus mejillas y clavaban la mirada en la música. Ahí venía un poquito de flauta —¡Muy bonita!— una pequeña cadena de gotas brillantes. Estaba segura de que se repetiría. Así fue; levantó la cabeza y sonrió.

Solo dos personas compartían su asiento «especial»: un refinado anciano con abrigo de terciopelo, sus manos entrelazadas sobre un gran bastón tallado, y una anciana corpulenta, sentada erguida, con una madeja sobre su delantal bordado. No hablaban. Era decepcionante, pues Miss Brill siempre aguardaba la conversación. Se había convertido en toda una experta, así lo creía, en escuchar como si no escuchara, en sentarse en la vida de otras personas solo por un minuto mientras hablaban a su alrededor.

Echó un vistazo, de reojo, a la pareja de ancianos. Tal vez se irían pronto. El domingo anterior tampoco había sido tan interesante como de costumbre. Un inglés y su esposa, él con un espantoso sombrero Panamá y ella con botines de abotonar. Y ella no había parado de hablar de que debía usar anteojos; sabía que los necesitaba; pero no serviría de nada conseguirlos; seguramente se romperían y nunca se mantendrían en su lugar. Y él había sido tan paciente. Le había sugerido todo: montura de oro, del tipo que se curva en las orejas, con pequeños soportes en el puente. No, nada la satisfacía. «¡Se me van a estar resbalando de la nariz!». Miss Brill había querido zarandearla.

Los ancianos permanecían sentados en la banca, quietos como estatuas. No importaba, siempre había una multitud para observar. De aquí para allá, frente a las jardineras y la rotonda de la banda, las parejas y los grupos desfilaban, se detenían a conversar, a saludar, a comprarle un ramo de flores al viejo mendigo que había sujetado su charola a las rejas. Niños pequeños corrían entre ellos, abalanzándose y riendo; hombrecitos con grandes corbatines blancos bajo la barbilla, mujercitas, muñequitas francesas, vestidas de terciopelo y encaje. Y algunas veces un chiquitín tambaleante venía de repente al claro balanceándose bajo los árboles, se detenía, se quedaba mirando y de repente «plop», se sentaba, hasta que su pequeña madre, los pies en alto, como una gallina joven, se apresuraba a su rescate regañándolo. Otras personas se sentaban en las bancas y en las sillas verdes, pero casi siempre eran las mismas, domingo tras domingo, y —Miss Brill lo había notado a menudo— la mayoría tenía algo curioso. Eran extraños, silenciosos, casi todos viejos y, por la forma en la que fijaban la mirada, parecía como si acabaran de salir de pequeñas habitaciones oscuras o incluso, ¡incluso armarios!

Detrás de la rotonda, los árboles esbeltos con hojas amarillas a punto de caer, y a través de ellos apenas una línea de mar, y más allá el cielo azul con nubes veteadas de oro.

¡Pam-pam-pam param-pam! ¡Param-pam! ¡Pam parim-pam pam pa!, tocó la banda.

Dos jovencitas de rojo pasaron y dos soldados jóvenes de azul se encontraron con ellas, y rieron y se emparejaron y se fueron de gancho. Dos campesinas con graciosos sombreros de paja pasaron, solemnemente, guiando hermosos burros de color humo. Una fría y pálida monja pasó con prisa. Una hermosa mujer apareció y dejó caer su ramo de violetas, y un niño pequeño la persiguió para entregárselas, y ella las tomó y las arrojó lejos, como si estuvieran envenenadas. ¡Válgame, Dios! ¡Miss Brill no sabía si sentir admiración o no! Y ahora un tocado de armiño y un caballero de gris se encontraron justo frente a ella. Él era alto, rígido, digno, y ella estaba usando el tocado de armiño que había comprado cuando su cabello era amarillo. Ahora todo, su cabello, su cara, incluso sus ojos, era del mismo color que el armiño andrajoso, y su mano, en su guante limpio, alzada para rozar sus labios, era una diminuta pata amarillenta. Oh, ella estaba tan complacida de verlo, ¡encantada! Prefería pensar que iban a encontrarse esa tarde. Describió dónde había estado: en todas partes, aquí, allá, junto al mar. El día era tan encantador, ¿no estaba de acuerdo? Y ¿no le gustaría, tal vez?… Pero él negó con la cabeza, prendió un cigarrillo, exhaló lentamente una profunda bocanada en el rostro de ella, y, pese a que ella aún seguía hablando y riendo, arrojó el fósforo y se marchó. El tocado de armiño estaba solo; sonrió más radiante que nunca. Pero incluso la banda parecía saber lo que ella estaba sintiendo y tocó más suave, tocó con ternura, y el golpeteo del tambor, «¡Bruto! ¡Bruto!», una y otra vez. ¿Qué haría ella? ¿Qué iba a ocurrir ahora? Pero mientras Miss Brill se preguntaba esto, el tocado de armiño se giró, levantó la mano como si hubiera visto a alguien más, mucho más agradable, a escasos pasos, y se alejó con andar ligero. Y la banda volvió a cambiar y tocó más deprisa, más alegre que nunca, y la pareja de ancianos en el asiento de Miss Brill se levantó y se marchó, y ese anciano curioso con bigotes largos avanzaba cojeando al ritmo de la música y casi lo chocan cuatro chicas que caminaban una junto a la otra.

¡Oh, qué fascinante era! ¡Cómo lo disfrutaba! ¡Cómo le encantaba sentarse allí, a observarlo todo! Era como una obra. Era exactamente como una obra. ¿Quién podría creer que el cielo en el fondo no estaba pintado? Pero no fue sino hasta que un pequeño perro café pasó trotando solemne y luego se alejó trotando lentamente, como un pequeño perro de «teatro», un pequeño perro al que habían drogado, que Miss Brill descubrió qué era lo que lo hacía tan emocionante. Todos estaban en el escenario. No solo eran la audiencia, no solo observaban; estaban actuando. Incluso ella tenía un papel y venía cada domingo. Sin duda alguien habría notado si ella no hubiera estado allí; después de todo, era parte de la función. ¡Qué extraño que nunca antes lo hubiera pensado de esa manera! Y aun así eso explicaba por qué ponía tanto empeño en salir de casa exactamente a la misma hora cada semana —para no llegar tarde a la función— y explicaba también por qué tenía una sensación tan extraña y tímida al decirle a sus estudiantes de inglés cómo pasaba las tardes de los domingos. ¡No era de extrañar! Miss Brill casi suelta una carcajada. Estaba en el escenario. Pensó en el caballero anciano e inválido al que le leía el periódico cuatro tardes a la semana mientras él dormía en el jardín. Ella ya se había acostumbrado bastante a la frágil cabeza en la almohada de algodón, los ojos hundidos, la boca abierta y la nariz respingada. Si él hubiera estado muerto ella podría no haberlo notado en semanas; no le habría importado. ¡Pero de repente él supo que quien le estaba leyendo el periódico era una actriz! «¡Una actriz!». La vieja cabeza levantada; dos puntos de luz titilaron en los ojos envejecidos. «Una actriz, ¿eh?». Y Miss Brill alisó el periódico como si fuera el manuscrito con su parte y respondió gentilmente: «Sí, he sido actriz por mucho tiempo».

La banda había tomado un descanso. Ahora empezaban de nuevo. Y lo que tocaban era cálido, soleado, aunque se sentía apenas un ligero escalofrío —un algo, ¿qué era? —no tristeza— no, no tristeza— un algo que te hacía querer cantar. La melodía ascendía, ascendía, la luz brillaba; y a Miss Brill le pareció que en un instante todos ellos, toda la compañía, empezarían a cantar. Los jóvenes, los que reían y se movían juntos, empezarían, y las voces de los hombres, muy decididas y valientes, se les unirían. Y entonces ella también, ella también, y los otros en las bancas, se unirían con una especie de acompañamiento, algo grave, que escasamente ascendía o descendía, algo muy hermoso, conmovedor. . . . Y los ojos de Miss Brill se llenaron de lágrimas y observó sonriendo a todos los miembros de la compañía. Sí, entendemos, entendemos, pensó —aunque ella no sabía qué era lo que ellos entendían—.

Justo en ese momento llegaron un chico y una chica y se sentaron donde había estado la pareja de ancianos. Estaban bellamente vestidos; estaban enamorados. El héroe y la heroína, por supuesto, recién llegados del yate del padre del chico. Y aún cantando sin voz , aún con una sonrisa trémula, Miss Brill se dispuso a escuchar.

—No, ahora no —dijo la chica—. Aquí no, no puedo.

—Pero, ¿por qué? ¿Por ese estúpido vejestorio de allá? —preguntó el chico—. ¿Al fin y al cabo para qué viene? ¿Quién la quiere? ¿Por qué no deja esa cara tan vieja y ridícula en casa?

—Es la pi-piel lo que me causa tanta gracia —dijo la chica mientras soltaba una risita—. Es igualita a un merlán frito.

—¡Ah, ya me tienes harto! –dijo el chico susurrando con enojo. Luego añadió—: dime, ma petite chère…

—No, aquí no —dijo la chica—. Todavía no.

De camino a casa solía comprar una rebanada de pastel de miel en la panadería. Ese era el gusto que se daba los domingos. A veces había una almendra en su rebanada, a veces no. Esto marcaba una gran diferencia. Si había una almendra era como llevarse a casa un regalo diminuto —una sorpresa— algo que bien podría no haber estado allí. Los domingos de almendra se apresuraba y encendía el fósforo para la tetera de un modo bastante vivaz.

Pero hoy no se detuvo en la panadería. Subió las escaleras, fue a la pequeña habitación oscura —la habitación parecida a un armario— y se sentó sobre el edredón rojo. Permaneció sentada allí durante mucho tiempo. La caja de donde había salido la piel estaba sobre la cama. Se desabrochó el cuello deprisa; deprisa, sin mirar, lo colocó adentro. Pero cuando puso la tapa creyó escuchar que algo lloraba.

Esta traducción fue el resultado del trabajo colaborativo realizado en 2025 por los estudiantes del Diplomado en Traducción Literaria de la Universidad Central. En ella participaron Luisa Peña, Katherine Leguizamón, Paula Muñoz, Sabrina García, Laura Toloza, Laura Cortés, Adriana García, Lizeth Sierra, Avril Romero, Paula Sánchez, Heidy Martínez, Ingrid Delgado y Jairo Pérez. La coordinación del proceso estuvo a cargo del profesor del diplomado, Alfonso Conde.