El cabuliwallah

Traducción del inglés por Diana Milena Castro Urrea

Texto original en bengalí de Rabindranath Tagore, traducido al inglés por su autor y Charles Andrews

Edición por Daniela Arias y Alejandro Ramírez Pulido

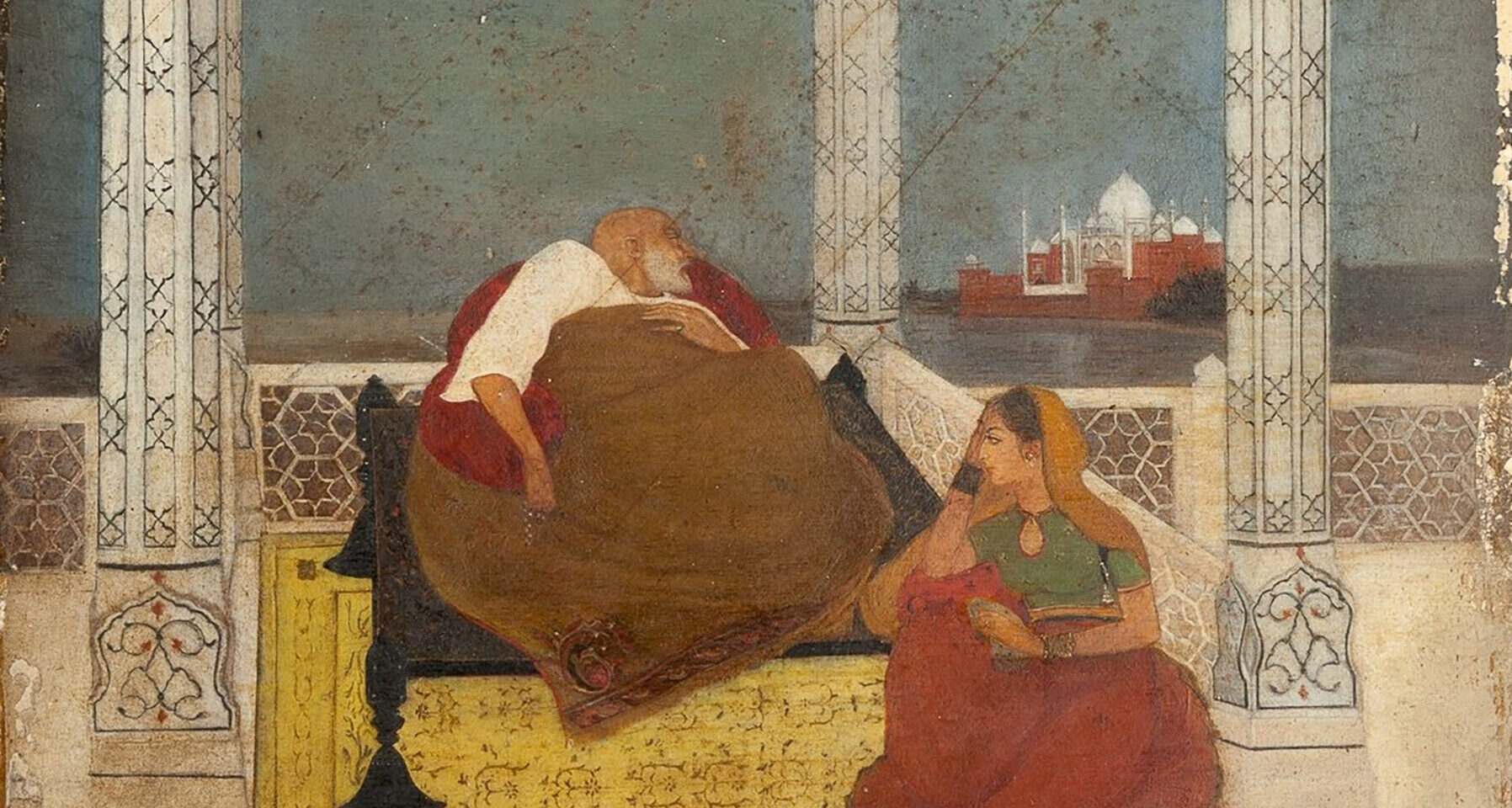

Imagen: «The Passing of Shah Jahan» de Abanindranath Tagore

Mi hija Mini tiene cinco años y no puede pasar un minuto sin parlotear. Realmente creo que en toda su vida no ha desperdiciado ni un instante en silencio. Su mamá a veces se desespera con tanta cháchara y trata de callarla, pero yo no. Ver a Mini callada es antinatural, y es algo que no soporto por mucho tiempo. Por eso, cuando hablo con ella la conversación es siempre animada.

Una mañana, por ejemplo, mientras estaba en medio del capítulo diecisiete de mi nueva novela, mi pequeña Mini se metió a escondidas en la habitación, me agarró la mano y me dijo:

—¡Papá! ¡Ramdayal, el portero, dice kuervo en vez de cuervo! ¡No sabe nada, ¿cierto?!

Antes de que pudiera explicarle las diferencias de los lenguajes de este mundo, ella ya se había embarcado en la corriente de otro tema.

—¿Tú qué piensas, papá? ¡Bhola dice que en las nubes hay un elefante echando agua por la trompa, y que por eso llueve!

Y entonces, mientras yo seguía sentado tratando de encontrar qué responder a lo último, dijo de nuevo precipitada:

—¡Papá! ¿Qué relación tiene mamá contigo?

—¡Es mi querida hermanita por ley! —musité sin querer para mis adentros, pero con cara seria logré responder—: ¡Anda a jugar con Bhola, Mini! ¡Estoy ocupado!

La ventana de mi estudio da a la calle. Mini se había sentado a mis pies, cerca de mi mesa, y jugaba tranquila, tamborileando con los dedos sobre sus rodillas. Yo estaba concentrado en el capítulo diecisiete de mi novela, donde Protrap Singh, el héroe, acababa de atrapar en sus brazos a Kanchanlata, la heroína, y estaba a punto de escapar con ella por la ventana del tercer piso del castillo, cuando, de pronto, Mini dejó de jugar, corrió hacia la ventana y gritó:

—¡Un cabuliwallah! ¡Un cabuliwallah!

Y sí, allí abajo, caminando despacio por la calle, iba un cabuliwallah [1]. Vestía ropas sueltas y algo sucias, típicas de su gente, con un turbante alto. Llevaba un costal a la espalda y unas cajas de uvas en la mano.

No podría decir con certeza qué sintió mi hija al verlo, pero empezó a llamarlo a gritos. “¡Ah!”, pensé. Va a entrar, y nunca terminaré el capítulo diecisiete. Justo en ese momento, el cabuliwallah se giró y miró a la niña. Al verlo, ella se asustó tanto que salió corriendo a buscar refugio con su mamá y desapareció. Ella tenía la ciega creencia de que en el costal de aquel hombre grande podía haber dos o tres niños como ella, metidos ahí dentro. El vendedor ambulante entró por la puerta de mi casa y me saludó con una sonrisa en el rostro.

La situación de mi héroe y mi heroína era tan delicada que mi primer impulso fue detenerme y comprarle algo, considerando que ya habían llamado al hombre. Hice unas pequeñas compras y empezamos a conversar sobre Abdurrahman, los rusos, los ingleses y la política fronteriza. Cuando estaba por irse, me preguntó:

—¿Y en dónde está la niña, señor?

Y yo, pensando que Mini debía superar ese miedo infundado, pedí que la trajeran.

Ella se paró junto a mi silla, y miró al cabuliwala y su costal. Él le ofreció nueces y uvas pasas, pero ella no se dejó tentar y solo se aferró más a mí, ahora con más dudas.

Así fue su primer encuentro.

No obstante, pocos días después, al salir de la casa una mañana me llevé una gran sorpresa al ver a Mini sentada en una banca cerca de la puerta, riendo y conversando con el gran Cabuliwallah sentado a sus pies. Al parecer, en toda su vida, mi pequeña hija no había encontrado un oyente tan paciente, salvo por su padre. Una esquina de su pequeño sari ya estaba llena de almendras y uvas pasas; regalo de su visitante.

—¿Por qué le diste eso? —le pregunté, sacando una moneda de ocho annas, y se la entregué al hombre. Él aceptó el dinero sin objetar y se lo guardó en el bolsillo.

Desafortunadamente, al volver una hora más tarde, ¡encontré que esa pobre moneda había causado el doble de problemas de lo que valía!, porque que el Cabuliwallah se la había dado a Mini, y su mamá, al ver el objeto brillante y redondo, le reclamó a la niña:

—¿De dónde sacaste esa moneda de ocho annas?

—El Cabuliwallah me la dio —dijo Mini con toda tranquilidad.

—¿¡El Cabuliwallah te la dio!? —exclamó su madre, muy escandalizada—. ¡Ay, Mini! ¿Cómo pudiste aceptársela?

Justo en ese momento entré yo, y la salvé del regaño inminente, aprovechando para hacer mis propias averiguaciones.

Descubrí que no era ni la primera ni la segunda vez que se veían. El Cabuliwallah había vencido el miedo inicial de la niña con una hábil estrategia de sobornos a punta de nueces y almendras, y ahora los dos eran grandes amigos.

Tenían entre ellos muchos chistes pintorescos que les causaban gran diversión. Mini, sentada frente a él, mirando hacia abajo desde su pequeña y digna estatura a ese hombre gigantesco, le decía entre risas:

—Oye, Cabuliwallah, Cabuliwallah, ¿qué llevas en ese costal?

Y él respondía, con su acento nasal de hombre de montaña:

—¡Un elefante!

Quizás no sea motivo suficiente para tanta risa, pero ¡cómo disfrutaban ese chistecito los dos! Para mí, siempre había habido algo extrañamente fascinante en las conversaciones entre niños y adultos.

Luego, el Cabuliwallah, para no quedarse atrás, lanzaba su propia pregunta:

—Bueno, niña, ¿y cuándo te vas para la casa de tu suegro?

Ahora, la mayoría de las muchachas bengalíes han oído hablar desde muy pequeñas de la ‘casa del suegro’; pero como nosotros éramos algo más modernos, habíamos evitado tocar esos temas con Mini, así que seguramente la pregunta la había dejado un poco confundida. Aun así, ella no se dejaba ver en apuros, y con astucia le respondía:

—¿Y tú vas para allá?

Entre los hombres de la clase del Cabuliwallah, sin embargo, es bien sabido que ‘la casa del suegro’ tiene un doble sentido: es un eufemismo para referirse a la cárcel, ese lugar donde, según dicen, a uno lo cuidan bien sin que tenga que pagar nada. En ese sentido tomaba el robusto vendedor ambulante la pregunta de mi hija.

—¡Ah! —decía, sacudiendo el puño hacia un policía imaginario—, ¡ya verán cómo le doy duro a ese suegro mío!

Y al escucharlo, imaginándose al pobre suegro apaleado, Mini soltaba una carcajada tras otra, a las que su formidable amigo no tardaba en unirse.

Eran mañanas de otoño, la misma época del año en la que, en otros tiempos, los reyes salían a conquistar tierras; y yo, sin moverme jamás de mi pequeño rincón en Calcuta, dejaba que mi mente vagara por todo el mundo. Al escuchar el nombre de otro país, mi corazón se volcaba hacia este, y al ver a un extranjero en las calles, comenzaba a tejer una red de sueños: las montañas, los valles y los bosques de su tierra lejana, con su cabaña en medio del paisaje, y la vida libre e independiente de esos parajes remotos. Quizá esas escenas de viaje se aparecían en mi imaginación con mayor intensidad precisamente porque yo llevaba una vida tan sedentaria, por lo que una invitación a viajar habría caído sobre mí como un rayo.

En presencia de aquel Cabuliwallah, me sentía transportado de inmediato al pie de áridos picos montañosos, con estrechos desfiladeros retorciéndose entre las alturas imponentes. Podía ver la caravana de camellos cargando mercancía, y al grupo de mercaderes con turbante portando sus extrañas armas antiguas y algunas de sus lanzas, descendiendo hacia las llanuras. Lo veía todo… hasta que, en momentos así, la madre de Mini intervenía, suplicándome que “tuviera cuidado con ese hombre”.

La madre de Mini, lamentablemente, es una mujer muy temerosa. Cada vez que oye un ruido en la calle, o ve gente acercándose a la casa, enseguida asume que son ladrones, borrachos, serpientes, tigres, malaria, cucarachas, orugas, o un marinero inglés. A pesar de todos estos años de experiencia, ella no había logrado superar su miedo. Así que vivía llena de sospechas respecto al Cabuliwallah y me pedía con insistencia que lo vigilara bien.

Yo trataba de ahuyentar suavemente sus temores con una risa , pero entonces ella se volvía hacia mí con gesto serio y me lanzaba preguntas solemnes.

—¿Acaso nunca hubo niños secuestrados?

—¿No es cierto que hay esclavitud en Kabul?

—¿Tan absurdo te parece que ese hombre tan grande pueda llevarse a una niña tan pequeña?

Yo le respondía que, aunque no imposible, era bastante improbable. Pero eso no bastaba, y su angustia persistía. Como era una angustia infundada, no me parecía justo prohibirle la entrada al hombre, así que la amistad entre él y Mini continuó sin obstáculos.

Cada año a mediados de enero, Rahmun, el Cabuliwallah, solía regresar a su país y, cuando se acercaba la fecha, andaba muy ocupado yendo de casa en casa cobrando sus deudas. Este año, sin embargo, siempre encontraba tiempo para pasar a ver a Mini. Un observador externo podría tener la impresión de que había una especie de conspiración entre los dos, porque si no venía en la mañana, aparecía por la tarde.

Incluso para mí era un poco desconcertante, de vez en cuando, encontrar repentinamente en el rincón de una habitación oscura a este hombre alto, de ropas sueltas y lleno de bolsas; pero cuando Mini entraba corriendo, sonriente con su «¡Oh, Cabuliwallah! ¡Cabuliwallah!» y los dos amigos, tan distantes en edad, volvían a sus risas y bromas de siempre, me sentía tranquilo.

Una mañana, pocos días antes de que él hubiera decidido partir, estaba corrigiendo mis impresiones de prueba en el estudio. Hacía frío. A través de la ventana, los rayos del sol tocaban mis pies, y ese leve calor era muy bienvenido. Eran casi las ocho y los primeros transeúntes regresaban a casa, con la cabeza cubierta. De pronto, escuché un alboroto en la calle y, al asomarme, vi a Rahmun siendo llevado, atado, entre dos policías, seguidos por un grupo de niños curiosos. Había manchas de sangre en la ropa del Cabuliwallah, y uno de los policías llevaba un cuchillo. Salí apresurado, los detuve y pregunté qué significaba todo eso. Unos me dijeron una cosa, otros otra, y así supe que un vecino le debía dinero al vendedor por un chal Rampuri, pero que falsamente había negado haberle comprado. En medio de la discusión, Rahmun lo había golpeado. Ahora, enardecido, el prisionero empezó a insultar a su enemigo cuando, de pronto, en una de las terrazas de mi casa apareció mi pequeña Mini con su exclamación de siempre:

—¡Oh, Cabuliwallah! ¡Cabuliwallah!

El rostro de Rahmun se iluminó al verla. Ese día no llevaba su bolsa bajo el brazo, así que ella no podía hablar con él del elefante. Entonces pasó a la siguiente pregunta: “¿Vas a casa de tu suegro?” Rahmun rió y dijo:

—¡Justo allá voy, pequeñita!

Luego, al notar que la respuesta no divertía a la niña, levantó sus manos encadenadas.

—¡Ali! —dijo— ¡le habría dado una paliza a ese viejo suegro, pero tengo las manos atadas!

Acusado de agresión con intención de matar, Rahmun fue condenado a varios años de prisión.

El tiempo pasó y él fue olvidado. El trabajo de siempre, en el lugar de siempre que seguía siendo nuestro; y rara vez pensábamos en aquel montañés que antaño fue libre y que ahora pasaba sus años en prisión. Incluso mi alegre Mini, debo confesar con vergüenza, olvidó a su viejo amigo. Nuevas compañías llenaron su vida. Al crecer, pasó más tiempo con otras niñas. Tanto así que ya no venía, como antes, a la habitación de su padre. Casi no hablábamos entre nosotros.

Pasaron los años. Era nuevamente otoño, y habíamos hecho los arreglos para el matrimonio de Mini. Se celebraría durante las vacaciones del Puja. Con el regreso de Durga a Kailas, la luz de nuestro hogar también partiría a la casa de su esposo, dejando a su padre en las sombras.

La mañana era radiante. Tras las lluvias, el aire parecía purificado, y los rayos del sol se veían como oro puro. Tan brillantes eran que daban una belleza especial incluso a los sórdidos muros de ladrillo de nuestras calles de Calcuta. Desde el amanecer, las flautas de boda resonaban, y con cada nota mi corazón latía con más fuerza. El lamento de la melodía Bhairavi parecía intensificar mi dolor ante la inminente separación. Mi Mini se casaría esa misma noche.

Desde temprano, la casa estaba llena de ruido y ajetreo. En el patio, había que colgar el toldo sobre los postes de bambú; los candelabros, con su tintineo, debían instalarse en cada habitación y en la terraza. La prisa y la emoción no tenían fin. Yo estaba sentado en mi estudio, revisando las cuentas, cuando alguien entró, saludó con respeto y se plantó frente a mí. Era Rahmun, el Cabuliwallah. Al principio no lo reconocí. No tenía su bolsa, ni el cabello largo, ni el vigor de antes. Pero al sonreír, lo reconocí.

—¿Cuándo llegaste, Rahmun? —le pregunté.

—Anoche —respondió—, salí de la cárcel.

Sus palabras me chocaron. Nunca había conversado con alguien que hubiese herido a otro y sentí mi corazón encogerse al pensar en eso, como si con su aparición el día tuviese un mal augurio.

—Estamos en medio de las ceremonias —dije—, y estoy ocupado. ¿Podrías venir otro día?

De inmediato se dio la vuelta para irse; pero, al llegar a la puerta, vaciló y dijo:

—¿No podría ver a la niña, señor, por un momento? —Creía que Mini seguía siendo la misma. La imaginaba corriendo hacia él, como antes, diciendo «¡Oh Cabuliwallah! ¡Cabuliwallah!» También creyó que reirían y charlarían como en los viejos tiempos. De hecho, en memoria de aquellos días, traía, cuidadosamente envueltos en papel, unas cuantas almendras, pasas y uvas que había conseguido de algún paisano, ya que su propio fondo se había agotado.

—Hay una ceremonia en casa, y no podrás ver a nadie hoy— repetí.

El rostro del hombre se entristeció. Me miró con nostalgia un momento, dijo «Buen día» y se marchó. Me sentí un poco apenado, y estuve a punto de llamarlo, pero vi que regresaba por su cuenta. Se acercó, extendió sus ofrendas y dijo:

—Traje estas cositas, señor, para la niña. ¿Podría dárselas usted?

Las tomé y me dispuse a pagarle, pero él me detuvo con la mano.

—¡Usted es muy amable, señor! Guárdeme en su recuerdo. ¡No me dé dinero! Usted tiene una hija pequeña; yo también tengo una parecida, allá en mi tierra. Pienso en ella y por eso traigo frutas para su niña, no para lucrarme.

Dicho esto, metió la mano dentro de su gran túnica suelta y sacó un pedazo pequeño y sucio de papel. Con mucho cuidado lo desplegó y lo alisó sobre mi mesa con ambas manos. Llevaba la impresión de una manita. No era una fotografía. Tampoco un dibujo. Era la impresión de una mano untada de tinta, extendida sobre el papel. Ese toque de su pequeña hija lo había llevado siempre en su corazón mientras, año tras año, venía a Calcuta a vender sus mercancías en la calle.

Las lágrimas inundaron mis ojos. Olvidé que él era un pobre vendedor de frutas de Kabul, mientras que yo… pero no, ¿qué era yo más que él? Él también era padre. Esa impresión de la mano de su pequeña Parbati, allá en su lejano hogar montañés, me hizo recordar a mi propia Mini.

Inmediatamente mandé llamar a Mini de los aposentos interiores. Hubo muchas objeciones, pero no las escuché. Vestida con la seda roja de su boda, con la pasta de sándalo en la frente y adornada como una joven novia, Mini vino y se quedó parada, tímida, frente a mí.

El Cabuliwallah se mostró un poco desconcertado ante esa aparición. No pudo revivir su antigua amistad. Finalmente, sonrió y dijo:

—Pequeña, ¿vas a casa de tu suegro?

Pero Mini ahora comprendía el significado de la palabra suegro y ya no pudo responder como antes. Se sonrojó ante la pregunta y permaneció de pie, con la mirada baja y su rostro de novia agachado.

Recordé el día en que el Cabuliwallah y mi Mini se conocieron, y me invadió la tristeza. Cuando ella se fue, Rahmun suspiró profundamente y se sentó en el suelo. De pronto se le ocurrió que su hija también debía haber crecido en todo ese tiempo y que tendría que volver a hacerse amigo de ella. Seguramente ya no la encontraría como la había dejado. Además, ¿qué no habría podido pasarle en esos ocho años?

Sonaban las flautas nupciales y el sol otoñal, suave, se derramaba sobre nosotros. Pero Rahmun, sentado en un callejón de Calcuta, veía ante sí las montañas áridas de Afganistán.

Saqué un billete y se lo entregué.

—Regresa con tu hija, Rahmun, a tu tierra, y que la dicha de ese reencuentro traiga buena fortuna a la mía.

Después de hacer ese regalo, tuve que reducir algunos festejos. No pudimos tener las luces eléctricas que quería, ni la banda militar, y las damas de la casa estaban desanimadas por ello. Pero, para mí, el banquete de bodas fue más brillante al pensar que, en una tierra lejana, un padre ausente por mucho tiempo se reencontraba con su única hija.

[1] Término en bengalí que significa literalmente “el hombre de Kabul”. Se refiere a los comerciantes afganos, típicamente vendedores ambulantes, que viajaban a la India para vender productos secos, especias o textiles. En este cuento, el nombre no es solo un apodo descriptivo, sino que también funciona como una especie de identidad afectiva para el personaje. Por eso he mantenido en su forma original —Cabuliwallah— en lugar de traducirlo, para preservar su valor cultural, sonoridad y resonancia emocional dentro del texto.

My five years’ old daughter Mini cannot live without chattering. I really believe that in all her life she has not wasted a minute in silence. Her mother is often vexed at this, and would stop her prattle, but I would not. To see Mini quiet is unnatural, and I cannot bear it long. And so my own talk with her is always lively.

One morning, for instance, when I was in the midst of the seventeenth chapter of my new novel, my little Mini stole into the room, and putting her hand into mine, said:

«Father! Ramdayal the door-keeper calls a crow a krow! He doesn’t know anything, does he?»

Before I could explain to her the differences of language in this world, she was embarked on the full tide of another subject.

«What do you think, Father? Bhola says there is an elephant in the clouds, blowing water out of his trunk, and that is why it rains!»

And then, darting off anew, while I sat still making ready some reply to this last saying,

«Father! what relation is Mother to you?»

«My dear little sister in the law!» I murmured involuntarily to myself, but with a grave face contrived to answer: «Go and play with Bhola, Mini! I am busy!»

The window of my room overlooks the road. The child had seated herself at my feet near my table, and was playing softly, drumming on her knees. I was hard at work on my seventeenth chapter, where Protrap Singh, the hero, had just caught Kanchanlata, the heroine, in his arms, and was about to escape with her by the third story window of the castle, when all of a sudden Mini left her play, and ran to the window, crying.

«A Cabuliwallah! a Cabuliwallah!»

Sure enough in the street below was a Cabuliwallah, passing slowly along. He wore the loose soiled clothing of his people, with a tall turban; there was a bag on his back, and he carried boxes of grapes in his hand.

I cannot tell what were my daughter’s feelings at the sight of this man, but she began to call him loudly. «Ah!» I thought, «he will come in, and my seventeenth chapter will never be finished!» At which exact moment the Cabuliwallah turned, and looked up at the child. When she saw this, overcome by terror, she fled to her mother’s protection, and disappeared. She had a blind belief that inside the bag, which the big man carried, there were perhaps two or three other children like herself. The pedlar meanwhile entered my doorway, and greeted me with a smiling face.

So precarious was the position of my hero and my heroine, that my first impulse was to stop and buy something, since the man had been called. I made some small purchases, and a conversation began about Abdurrahman, the Russians, she English, and the Frontier Policy. As he was about to leave, he asked:

«And where is the little girl, sir?»

And I, thinking that Mini must get rid of her false fear, had her brought out.

She stood by my chair, and looked at the Cabuliwallah and his bag. He offered her nuts and raisins, but she would not be tempted, and only clung the closer to me, with all her doubts increased.

This was their first meeting.

One morning, however, not many days later, as I was leaving the house, I was startled to find Mini, seated on a bench near the door, laughing and talking, with the great Cabuliwallah at her feet. In all her life, it appeared; my small daughter had never found so patient a listener, save her father. And already the corner of her little sari was stuffed with almonds and raisins, the gift of her visitor.

«Why did you give her those?» I said, and taking out an eight-anna bit, I handed it to him. The man accepted the money without demur, and slipped it into his pocket.

Alas, on my return an hour later, I found the unfortunate coin had made twice its own worth of trouble! For the Cabuliwallah had given it to Mini, and her mother catching sight of the bright round object, had pounced on the child with.

«Where did you get that eight-anna bit?»

«The Cabuliwallah gave it me,» said Mini cheerfully.

«The Cabuliwallah gave it you!» cried her mother much shocked. «Oh, Mini! how could you take it from him?»

I, entering at the moment, saved her from impending disaster, and proceeded to make my own inquiries.

It was not the first or second time, I found, that the two had met. The Cabuliwallah had overcome the child’s first terror by a judicious bribery of nuts and almonds, and the two were now great friends.

They had many quaint jokes, which afforded them much amusement. Seated in front of him, looking down on his gigantic frame in all her tiny dignity, Mini would ripple her face with laughter, and begin:

«O Cabuliwallah, Cabuliwallah, what have you got in your bag?»

And he would reply, in the nasal accents of the mountaineer:

«An elephant!»

Not much cause for merriment, perhaps; but how they both enjoyed the witticism! And for me, this child’s talk with a grown-up man had always in it something strangely fascinating.

Then the Cabuliwallah, not to be behindhand, would take his turn:

«Well, little one, and when are you going to the father-in-law’s house?»

Now most small Bengali maidens have heard long ago about the father-in-law’s house; but we, being a little new-fangled, had kept these things from our child, and Mini at this question must have been a trifle bewildered. But she would not show it, and with ready tact replied:

«Are you going there?»

Amongst men of the Cabuliwallah’s class, however, it is well known that the words father-in-law’s house have a double meaning. It is a euphemism for jail, the place where we are well cared for, at no expense to ourselves. In this sense would the sturdy pedlar take my daughter’s question.

«Ah,» he would say, shaking his fist at an invisible policeman, «I will thrash my father-in-law!»

Hearing this, and picturing the poor discomfited relative, Mini would go off into peals of laughter, in which her formidable friend would join.

These were autumn mornings, the very time of year when kings of old went forth to conquest; and I, never stirring from my little corner in Calcutta, would let my mind wander over the whole world. At the very name of another country, my heart would go out to it, and at the sight of a foreigner in the streets, I would fall to weaving a network of dreams,—the mountains, the glens, and the forests of his distant home, with his cottage in its setting, and the free and independent life of far-away wilds. Perhaps the scenes of travel conjure themselves up before me, and pass and repass in my imagination all the more vividly, because I lead such a vegetable existence, that a call to travel would fall upon me like a thunderbolt.

In the presence of this Cabuliwallah, I was immediately transported to the foot of arid mountain peaks, with narrow little defiles twisting in and out amongst their towering heights. I could see the string of camels bearing the merchandise, and the company of turbaned merchants, carrying some of their queer old firearms, and some of their spears, journeying downward towards the plains. I could see—but at some such point Mini’s mother would intervene, imploring me to «beware of that man.»

Mini’s mother is unfortunately a very timid lady. Whenever she hears a noise in the street, or sees people coming towards the house, she always jumps to the conclusion that they are either thieves, or drunkards, or snakes, or tigers, or malaria or cockroaches, or caterpillars, or an English sailor. Even after all these years of experience, she is not able to overcome her terror. So she was full of doubts about the Cabuliwallah, and used to beg me to keep a watchful eye on him.

I tried to laugh her fear gently away, but then she would turn round on me seriously, and ask me solemn questions.

«Were children never kidnapped?»

«Was it, then, not true that there was slavery in Cabul?»

«Was it so very absurd that this big man should be able to carry off a tiny child?»

I urged that, though not impossible, it was highly improbable. But this was not enough, and her dread persisted. As it was indefinite, however, it did not seem right to forbid the man the house, and the intimacy went on unchecked.

Once a year in the middle of January Rahmun, the Cabuliwallah, was in the habit of returning to his country, and as the time approached he would be very busy, going from house to house collecting his debts. This year, however, he could always find time to come and see Mini. It would have seemed to an outsider that there was some conspiracy between the two, for when he could not come in the morning, he would appear in the evening.

Even to me it was a little startling now and then, in the corner of a dark room, suddenly to surprise this tall, loose-garmented, much bebagged man; but when Mini would run in smiling, with her, «O! Cabuliwallah! Cabuliwallah!» and the two friends, so far apart in age, would subside into their old laughter and their old jokes, I felt reassured.

One morning, a few days before he had made up his mind to go, I was correcting my proof sheets in my study. It was chilly weather. Through the window the rays of the sun touched my feet, and the slight warmth was very welcome. It was almost eight o’clock, and the early pedestrians were returning home, with their heads covered. All at once, I heard an uproar in the street, and, looking out, saw Rahmun being led away bound between two policemen, and behind them a crowd of curious boys. There were blood-stains on the clothes of the Cabuliwallah, and one of the policemen carried a knife. Hurrying out, I stopped them, and enquired what it all meant. Partly from one, partly from another, I gathered that a certain neighbour had owed the pedlar something for a Rampuri shawl, but had falsely denied having bought it, and that in the course of the quarrel, Rahmun had struck him. Now in the heat of his excitement, the prisoner began calling his enemy all sorts of names, when suddenly in a verandah of my house appeared my little Mini, with her usual exclamation:

«O Cabuliwallah! Cabuliwallah!»

Rahmun’s face lighted up as he turned to her. He had no bag under his arm today, so she could not discuss the elephant with him. She at once therefore proceeded to the next question: «Are you going to the father-in-law’s house?» Rahmun laughed and said:

«Just where I am going, little one!»

Then seeing that the reply did not amuse the child, he held up his fettered hands.

«Ali,» he said, «I would have thrashed that old father-in-law, but my hands are bound!»

On a charge of murderous assault, Rahmun was sentenced to some years’ imprisonment.

Time passed away, and he was not remembered. The accustomed work in the accustomed place was ours, and the thought of the once-free mountaineer spending his years in prison seldom or never occurred to us. Even my light-hearted Mini, I am ashamed to say, forgot her old friend. New companions filled her life. As she grew older, she spent more of her time with girls. So much time indeed did she spend with them that she came no more, as she used to do, to her father’s room. I was scarcely on speaking terms with her.

Years had passed away. It was once more autumn and we had made arrangements for our Mini’s marriage. It was to take place during the Puja Holidays. With Durga returning to Kailas, the light of our home also was to depart to her husband’s house, and leave her father’s in the shadow.

The morning was bright. After the rains, there was a sense of ablution in the air, and the sun-rays looked like pure gold. So bright were they that they gave a beautiful radiance even to the sordid brick walls of our Calcutta lanes. Since early dawn to-day the wedding-pipes had been sounding, and at each beat my own heart throbbed. The wail of the tune, Bhairavi, seemed to intensify my pain at the approaching separation. My Mini was to be married to-night.

From early morning noise and bustle had pervaded the house. In the courtyard the canopy had to be slung on its bamboo poles; the chandeliers with their tinkling sound must be hung in each room and verandah. There was no end of hurry and excitement. I was sitting in my study, looking through the accounts, when some one entered, saluting respectfully, and stood before me. It was Rahmun the Cabuliwallah. At first I did not recognise him. He had no bag, nor the long hair, nor the same vigour that he used to have. But he smiled, and I knew him again.

«When did you come, Rahmun?» I asked him.

«Last evening,» he said, «I was released from jail.»

The words struck harsh upon my ears. I had never before talked with one who had wounded his fellow, and my heart shrank within itself, when I realised this, for I felt that the day would have been better-omened had he not turned up.

«There are ceremonies going on,» I said, «and I am busy. Could you perhaps come another day?»

At once he turned to go; but as he reached the door he hesitated, and said:

«May I not see the little one, sir, for a moment?» It was his belief that Mini was still the same. He had pictured her running to him as she used, calling «O Cabuliwallah! Cabuliwallah!» He had imagined too that they would laugh and talk together, just as of old. In fact, in memory of former days he had brought, carefully wrapped up in paper, a few almonds and raisins and grapes, obtained somehow from a countryman, for his own little fund was dispersed.

I said again: «There is a ceremony in the house, and you will not be able to see any one to-day.»

The man’s face fell. He looked wistfully at me for a moment, said «Good morning,» and went out. I felt a little sorry, and would have called him back, but I found he was returning of his own accord. He came close up to me holding out his offerings and said:

«I brought these few things, sir, for the little one. Will you give them to her?»

I took them and was going to pay him, but he caught my hand and said:

«You are very kind, sir! Keep me in your recollection. Do not offer me money!—You have a little girl, I too have one like her in my own home. I think of her, and bring fruits to your child, not to make a profit for myself.»

Saying this, he put his hand inside his big loose robe, and brought out a small and dirty piece of paper. With great care he unfolded this, and smoothed it out with both hands on my table. It bore the impression of a little band. Not a photograph. Not a drawing. The impression of an ink-smeared hand laid flat on the paper. This touch of his own little daughter had been always on his heart, as he had come year after year to Calcutta, to sell his wares in the streets.

Tears came to my eyes. I forgot that he was a poor Cabuli fruit-seller, while I was—but no, what was I more than he? He also was a father. That impression of the hand of his little Parbati in her distant mountain home reminded me of my own little Mini.

I sent for Mini immediately from the inner apartment. Many difficulties were raised, but I would not listen. Clad in the red silk of her wedding-day, with the sandal paste on her forehead, and adorned as a young bride, Mini came, and stood bashfully before me.

The Cabuliwallah looked a little staggered at the apparition. He could not revive their old friendship. At last he smiled and said:

«Little one, are you going to your father-in-law’s house?»

But Mini now understood the meaning of the word «father-in-law,» and she could not reply to him as of old. She flushed up at the question, and stood before him with her bride-like face turned down.

I remembered the day when the Cabuliwallah and my Mini had first met, and I felt sad. When she had gone, Rahmun heaved a deep sigh, and sat down on the floor. The idea had suddenly come to him that his daughter too must have grown in this long time, and that he would have to make friends with her anew. Assuredly he would not find her, as he used to know her. And besides, what might not have happened to her in these eight years?

The marriage-pipes sounded, and the mild autumn sun streamed round us. But Rahmun sat in the little Calcutta lane, and saw before him the barren mountains of Afghanistan.

I took out a bank-note, and gave it to him, saying:

«Go back to your own daughter, Rahmun, in your own country, and may the happiness of your meeting bring good fortune to my child!»

Having made this present, I had to curtail some of the festivities. I could not have the electric lights I had intended, nor the military band, and the ladies of the house were despondent at it. But to me the wedding feast was all the brighter for the thought that in a distant land a long-lost father met again with his only child.

(Fuente: «The Hungry Stones and Other Stories» de Rabindranath Tagore en Project Gutenberg)

My five years’ old daughter Mini cannot live without chattering. I really believe that in all her life she has not wasted a minute in silence. Her mother is often vexed at this, and would stop her prattle, but I would not. To see Mini quiet is unnatural, and I cannot bear it long. And so my own talk with her is always lively.

One morning, for instance, when I was in the midst of the seventeenth chapter of my new novel, my little Mini stole into the room, and putting her hand into mine, said:

«Father! Ramdayal the door-keeper calls a crow a krow! He doesn’t know anything, does he?»

Before I could explain to her the differences of language in this world, she was embarked on the full tide of another subject.

«What do you think, Father? Bhola says there is an elephant in the clouds, blowing water out of his trunk, and that is why it rains!»

And then, darting off anew, while I sat still making ready some reply to this last saying,

«Father! what relation is Mother to you?»

«My dear little sister in the law!» I murmured involuntarily to myself, but with a grave face contrived to answer: «Go and play with Bhola, Mini! I am busy!»

The window of my room overlooks the road. The child had seated herself at my feet near my table, and was playing softly, drumming on her knees. I was hard at work on my seventeenth chapter, where Protrap Singh, the hero, had just caught Kanchanlata, the heroine, in his arms, and was about to escape with her by the third story window of the castle, when all of a sudden Mini left her play, and ran to the window, crying.

«A Cabuliwallah! a Cabuliwallah!»

Sure enough in the street below was a Cabuliwallah, passing slowly along. He wore the loose soiled clothing of his people, with a tall turban; there was a bag on his back, and he carried boxes of grapes in his hand.

I cannot tell what were my daughter’s feelings at the sight of this man, but she began to call him loudly. «Ah!» I thought, «he will come in, and my seventeenth chapter will never be finished!» At which exact moment the Cabuliwallah turned, and looked up at the child. When she saw this, overcome by terror, she fled to her mother’s protection, and disappeared. She had a blind belief that inside the bag, which the big man carried, there were perhaps two or three other children like herself. The pedlar meanwhile entered my doorway, and greeted me with a smiling face.

So precarious was the position of my hero and my heroine, that my first impulse was to stop and buy something, since the man had been called. I made some small purchases, and a conversation began about Abdurrahman, the Russians, she English, and the Frontier Policy. As he was about to leave, he asked:

«And where is the little girl, sir?»

And I, thinking that Mini must get rid of her false fear, had her brought out.

She stood by my chair, and looked at the Cabuliwallah and his bag. He offered her nuts and raisins, but she would not be tempted, and only clung the closer to me, with all her doubts increased.

This was their first meeting.

One morning, however, not many days later, as I was leaving the house, I was startled to find Mini, seated on a bench near the door, laughing and talking, with the great Cabuliwallah at her feet. In all her life, it appeared; my small daughter had never found so patient a listener, save her father. And already the corner of her little sari was stuffed with almonds and raisins, the gift of her visitor.

«Why did you give her those?» I said, and taking out an eight-anna bit, I handed it to him. The man accepted the money without demur, and slipped it into his pocket.

Alas, on my return an hour later, I found the unfortunate coin had made twice its own worth of trouble! For the Cabuliwallah had given it to Mini, and her mother catching sight of the bright round object, had pounced on the child with.

«Where did you get that eight-anna bit?»

«The Cabuliwallah gave it me,» said Mini cheerfully.

«The Cabuliwallah gave it you!» cried her mother much shocked. «Oh, Mini! how could you take it from him?»

I, entering at the moment, saved her from impending disaster, and proceeded to make my own inquiries.

It was not the first or second time, I found, that the two had met. The Cabuliwallah had overcome the child’s first terror by a judicious bribery of nuts and almonds, and the two were now great friends.

They had many quaint jokes, which afforded them much amusement. Seated in front of him, looking down on his gigantic frame in all her tiny dignity, Mini would ripple her face with laughter, and begin:

«O Cabuliwallah, Cabuliwallah, what have you got in your bag?»

And he would reply, in the nasal accents of the mountaineer:

«An elephant!»

Not much cause for merriment, perhaps; but how they both enjoyed the witticism! And for me, this child’s talk with a grown-up man had always in it something strangely fascinating.

Then the Cabuliwallah, not to be behindhand, would take his turn:

«Well, little one, and when are you going to the father-in-law’s house?»

Now most small Bengali maidens have heard long ago about the father-in-law’s house; but we, being a little new-fangled, had kept these things from our child, and Mini at this question must have been a trifle bewildered. But she would not show it, and with ready tact replied:

«Are you going there?»

Amongst men of the Cabuliwallah’s class, however, it is well known that the words father-in-law’s house have a double meaning. It is a euphemism for jail, the place where we are well cared for, at no expense to ourselves. In this sense would the sturdy pedlar take my daughter’s question.

«Ah,» he would say, shaking his fist at an invisible policeman, «I will thrash my father-in-law!»

Hearing this, and picturing the poor discomfited relative, Mini would go off into peals of laughter, in which her formidable friend would join.

These were autumn mornings, the very time of year when kings of old went forth to conquest; and I, never stirring from my little corner in Calcutta, would let my mind wander over the whole world. At the very name of another country, my heart would go out to it, and at the sight of a foreigner in the streets, I would fall to weaving a network of dreams,—the mountains, the glens, and the forests of his distant home, with his cottage in its setting, and the free and independent life of far-away wilds. Perhaps the scenes of travel conjure themselves up before me, and pass and repass in my imagination all the more vividly, because I lead such a vegetable existence, that a call to travel would fall upon me like a thunderbolt.

In the presence of this Cabuliwallah, I was immediately transported to the foot of arid mountain peaks, with narrow little defiles twisting in and out amongst their towering heights. I could see the string of camels bearing the merchandise, and the company of turbaned merchants, carrying some of their queer old firearms, and some of their spears, journeying downward towards the plains. I could see—but at some such point Mini’s mother would intervene, imploring me to «beware of that man.»

Mini’s mother is unfortunately a very timid lady. Whenever she hears a noise in the street, or sees people coming towards the house, she always jumps to the conclusion that they are either thieves, or drunkards, or snakes, or tigers, or malaria or cockroaches, or caterpillars, or an English sailor. Even after all these years of experience, she is not able to overcome her terror. So she was full of doubts about the Cabuliwallah, and used to beg me to keep a watchful eye on him.

I tried to laugh her fear gently away, but then she would turn round on me seriously, and ask me solemn questions.

«Were children never kidnapped?»

«Was it, then, not true that there was slavery in Cabul?»

«Was it so very absurd that this big man should be able to carry off a tiny child?»

I urged that, though not impossible, it was highly improbable. But this was not enough, and her dread persisted. As it was indefinite, however, it did not seem right to forbid the man the house, and the intimacy went on unchecked.

Once a year in the middle of January Rahmun, the Cabuliwallah, was in the habit of returning to his country, and as the time approached he would be very busy, going from house to house collecting his debts. This year, however, he could always find time to come and see Mini. It would have seemed to an outsider that there was some conspiracy between the two, for when he could not come in the morning, he would appear in the evening.

Even to me it was a little startling now and then, in the corner of a dark room, suddenly to surprise this tall, loose-garmented, much bebagged man; but when Mini would run in smiling, with her, «O! Cabuliwallah! Cabuliwallah!» and the two friends, so far apart in age, would subside into their old laughter and their old jokes, I felt reassured.

One morning, a few days before he had made up his mind to go, I was correcting my proof sheets in my study. It was chilly weather. Through the window the rays of the sun touched my feet, and the slight warmth was very welcome. It was almost eight o’clock, and the early pedestrians were returning home, with their heads covered. All at once, I heard an uproar in the street, and, looking out, saw Rahmun being led away bound between two policemen, and behind them a crowd of curious boys. There were blood-stains on the clothes of the Cabuliwallah, and one of the policemen carried a knife. Hurrying out, I stopped them, and enquired what it all meant. Partly from one, partly from another, I gathered that a certain neighbour had owed the pedlar something for a Rampuri shawl, but had falsely denied having bought it, and that in the course of the quarrel, Rahmun had struck him. Now in the heat of his excitement, the prisoner began calling his enemy all sorts of names, when suddenly in a verandah of my house appeared my little Mini, with her usual exclamation:

«O Cabuliwallah! Cabuliwallah!»

Rahmun’s face lighted up as he turned to her. He had no bag under his arm today, so she could not discuss the elephant with him. She at once therefore proceeded to the next question: «Are you going to the father-in-law’s house?» Rahmun laughed and said:

«Just where I am going, little one!»

Then seeing that the reply did not amuse the child, he held up his fettered hands.

«Ali,» he said, «I would have thrashed that old father-in-law, but my hands are bound!»

On a charge of murderous assault, Rahmun was sentenced to some years’ imprisonment.

Time passed away, and he was not remembered. The accustomed work in the accustomed place was ours, and the thought of the once-free mountaineer spending his years in prison seldom or never occurred to us. Even my light-hearted Mini, I am ashamed to say, forgot her old friend. New companions filled her life. As she grew older, she spent more of her time with girls. So much time indeed did she spend with them that she came no more, as she used to do, to her father’s room. I was scarcely on speaking terms with her.

Years had passed away. It was once more autumn and we had made arrangements for our Mini’s marriage. It was to take place during the Puja Holidays. With Durga returning to Kailas, the light of our home also was to depart to her husband’s house, and leave her father’s in the shadow.

The morning was bright. After the rains, there was a sense of ablution in the air, and the sun-rays looked like pure gold. So bright were they that they gave a beautiful radiance even to the sordid brick walls of our Calcutta lanes. Since early dawn to-day the wedding-pipes had been sounding, and at each beat my own heart throbbed. The wail of the tune, Bhairavi, seemed to intensify my pain at the approaching separation. My Mini was to be married to-night.

From early morning noise and bustle had pervaded the house. In the courtyard the canopy had to be slung on its bamboo poles; the chandeliers with their tinkling sound must be hung in each room and verandah. There was no end of hurry and excitement. I was sitting in my study, looking through the accounts, when some one entered, saluting respectfully, and stood before me. It was Rahmun the Cabuliwallah. At first I did not recognise him. He had no bag, nor the long hair, nor the same vigour that he used to have. But he smiled, and I knew him again.

«When did you come, Rahmun?» I asked him.

«Last evening,» he said, «I was released from jail.»

The words struck harsh upon my ears. I had never before talked with one who had wounded his fellow, and my heart shrank within itself, when I realised this, for I felt that the day would have been better-omened had he not turned up.

«There are ceremonies going on,» I said, «and I am busy. Could you perhaps come another day?»

At once he turned to go; but as he reached the door he hesitated, and said:

«May I not see the little one, sir, for a moment?» It was his belief that Mini was still the same. He had pictured her running to him as she used, calling «O Cabuliwallah! Cabuliwallah!» He had imagined too that they would laugh and talk together, just as of old. In fact, in memory of former days he had brought, carefully wrapped up in paper, a few almonds and raisins and grapes, obtained somehow from a countryman, for his own little fund was dispersed.

I said again: «There is a ceremony in the house, and you will not be able to see any one to-day.»

The man’s face fell. He looked wistfully at me for a moment, said «Good morning,» and went out. I felt a little sorry, and would have called him back, but I found he was returning of his own accord. He came close up to me holding out his offerings and said:

«I brought these few things, sir, for the little one. Will you give them to her?»

I took them and was going to pay him, but he caught my hand and said:

«You are very kind, sir! Keep me in your recollection. Do not offer me money!—You have a little girl, I too have one like her in my own home. I think of her, and bring fruits to your child, not to make a profit for myself.»

Saying this, he put his hand inside his big loose robe, and brought out a small and dirty piece of paper. With great care he unfolded this, and smoothed it out with both hands on my table. It bore the impression of a little band. Not a photograph. Not a drawing. The impression of an ink-smeared hand laid flat on the paper. This touch of his own little daughter had been always on his heart, as he had come year after year to Calcutta, to sell his wares in the streets.

Tears came to my eyes. I forgot that he was a poor Cabuli fruit-seller, while I was—but no, what was I more than he? He also was a father. That impression of the hand of his little Parbati in her distant mountain home reminded me of my own little Mini.

I sent for Mini immediately from the inner apartment. Many difficulties were raised, but I would not listen. Clad in the red silk of her wedding-day, with the sandal paste on her forehead, and adorned as a young bride, Mini came, and stood bashfully before me.

The Cabuliwallah looked a little staggered at the apparition. He could not revive their old friendship. At last he smiled and said:

«Little one, are you going to your father-in-law’s house?»

But Mini now understood the meaning of the word «father-in-law,» and she could not reply to him as of old. She flushed up at the question, and stood before him with her bride-like face turned down.

I remembered the day when the Cabuliwallah and my Mini had first met, and I felt sad. When she had gone, Rahmun heaved a deep sigh, and sat down on the floor. The idea had suddenly come to him that his daughter too must have grown in this long time, and that he would have to make friends with her anew. Assuredly he would not find her, as he used to know her. And besides, what might not have happened to her in these eight years?

The marriage-pipes sounded, and the mild autumn sun streamed round us. But Rahmun sat in the little Calcutta lane, and saw before him the barren mountains of Afghanistan.

I took out a bank-note, and gave it to him, saying:

«Go back to your own daughter, Rahmun, in your own country, and may the happiness of your meeting bring good fortune to my child!»

Having made this present, I had to curtail some of the festivities. I could not have the electric lights I had intended, nor the military band, and the ladies of the house were despondent at it. But to me the wedding feast was all the brighter for the thought that in a distant land a long-lost father met again with his only child.

Mi hija Mini tiene cinco años y no puede pasar un minuto sin parlotear. Realmente creo que en toda su vida no ha desperdiciado ni un instante en silencio. Su mamá a veces se desespera con tanta cháchara y trata de callarla, pero yo no. Ver a Mini callada es antinatural, y es algo que no soporto por mucho tiempo. Por eso, cuando hablo con ella la conversación es siempre animada.

Una mañana, por ejemplo, mientras estaba en medio del capítulo diecisiete de mi nueva novela, mi pequeña Mini se metió a escondidas en la habitación, me agarró la mano y me dijo:

—¡Papá! ¡Ramdayal, el portero, dice kuervo en vez de cuervo! ¡No sabe nada, ¿cierto?!

Antes de que pudiera explicarle las diferencias de los lenguajes de este mundo, ella ya se había embarcado en la corriente de otro tema.

—¿Tú qué piensas, papá? ¡Bhola dice que en las nubes hay un elefante echando agua por la trompa, y que por eso llueve!

Y entonces, mientras yo seguía sentado tratando de encontrar qué responder a lo último, dijo de nuevo precipitada:

—¡Papá! ¿Qué relación tiene mamá contigo?

—¡Es mi querida hermanita por ley! —musité sin querer para mis adentros, pero con cara seria logré responder—: ¡Anda a jugar con Bhola, Mini! ¡Estoy ocupado!

La ventana de mi estudio da a la calle. Mini se había sentado a mis pies, cerca de mi mesa, y jugaba tranquila, tamborileando con los dedos sobre sus rodillas. Yo estaba concentrado en el capítulo diecisiete de mi novela, donde Protrap Singh, el héroe, acababa de atrapar en sus brazos a Kanchanlata, la heroína, y estaba a punto de escapar con ella por la ventana del tercer piso del castillo, cuando, de pronto, Mini dejó de jugar, corrió hacia la ventana y gritó:

—¡Un cabuliwallah! ¡Un cabuliwallah!

Y sí, allí abajo, caminando despacio por la calle, iba un cabuliwallah. Vestía ropas sueltas y algo sucias, típicas de su gente, con un turbante alto. Llevaba un costal a la espalda y unas cajas de uvas en la mano.

No podría decir con certeza qué sintió mi hija al verlo, pero empezó a llamarlo a gritos. “¡Ah!”, pensé. Va a entrar, y nunca terminaré el capítulo diecisiete. Justo en ese momento, el cabuliwallah se giró y miró a la niña. Al verlo, ella se asustó tanto que salió corriendo a buscar refugio con su mamá y desapareció. Ella tenía la ciega creencia de que en el costal de aquel hombre grande podía haber dos o tres niños como ella, metidos ahí dentro. El vendedor ambulante entró por la puerta de mi casa y me saludó con una sonrisa en el rostro.

La situación de mi héroe y mi heroína era tan delicada que mi primer impulso fue detenerme y comprarle algo, considerando que ya habían llamado al hombre. Hice unas pequeñas compras y empezamos a conversar sobre Abdurrahman, los rusos, los ingleses y la política fronteriza. Cuando estaba por irse, me preguntó:

—¿Y en dónde está la niña, señor?

Y yo, pensando que Mini debía superar ese miedo infundado, pedí que la trajeran.

Ella se paró junto a mi silla, y miró al cabuliwala y su costal. Él le ofreció nueces y uvas pasas, pero ella no se dejó tentar y solo se aferró más a mí, ahora con más dudas.

Así fue su primer encuentro.

No obstante, pocos días después, al salir de la casa una mañana me llevé una gran sorpresa al ver a Mini sentada en una banca cerca de la puerta, riendo y conversando con el gran Cabuliwallah sentado a sus pies. Al parecer, en toda su vida, mi pequeña hija no había encontrado un oyente tan paciente, salvo por su padre. Una esquina de su pequeño sari ya estaba llena de almendras y uvas pasas; regalo de su visitante.

—¿Por qué le diste eso? —le pregunté, sacando una moneda de ocho annas, y se la entregué al hombre. Él aceptó el dinero sin objetar y se lo guardó en el bolsillo.

Desafortunadamente, al volver una hora más tarde, ¡encontré que esa pobre moneda había causado el doble de problemas de lo que valía!, porque que el Cabuliwallah se la había dado a Mini, y su mamá, al ver el objeto brillante y redondo, le reclamó a la niña:

—¿De dónde sacaste esa moneda de ocho annas?

—El Cabuliwallah me la dio —dijo Mini con toda tranquilidad.

—¿¡El Cabuliwallah te la dio!? —exclamó su madre, muy escandalizada—. ¡Ay, Mini! ¿Cómo pudiste aceptársela?

Justo en ese momento entré yo, y la salvé del regaño inminente, aprovechando para hacer mis propias averiguaciones.

Descubrí que no era ni la primera ni la segunda vez que se veían. El Cabuliwallah había vencido el miedo inicial de la niña con una hábil estrategia de sobornos a punta de nueces y almendras, y ahora los dos eran grandes amigos.

Tenían entre ellos muchos chistes pintorescos que les causaban gran diversión. Mini, sentada frente a él, mirando hacia abajo desde su pequeña y digna estatura a ese hombre gigantesco, le decía entre risas:

—Oye, Cabuliwallah, Cabuliwallah, ¿qué llevas en ese costal?

Y él respondía, con su acento nasal de hombre de montaña:

—¡Un elefante!

Quizás no sea motivo suficiente para tanta risa, pero ¡cómo disfrutaban ese chistecito los dos! Para mí, siempre había habido algo extrañamente fascinante en las conversaciones entre niños y adultos.

Luego, el Cabuliwallah, para no quedarse atrás, lanzaba su propia pregunta:

—Bueno, niña, ¿y cuándo te vas para la casa de tu suegro?

Ahora, la mayoría de las muchachas bengalíes han oído hablar desde muy pequeñas de la ‘casa del suegro’; pero como nosotros éramos algo más modernos, habíamos evitado tocar esos temas con Mini, así que seguramente la pregunta la había dejado un poco confundida. Aun así, ella no se dejaba ver en apuros, y con astucia le respondía:

—¿Y tú vas para allá?

Entre los hombres de la clase del Cabuliwallah, sin embargo, es bien sabido que ‘la casa del suegro’ tiene un doble sentido: es un eufemismo para referirse a la cárcel, ese lugar donde, según dicen, a uno lo cuidan bien sin que tenga que pagar nada. En ese sentido tomaba el robusto vendedor ambulante la pregunta de mi hija.

—¡Ah! —decía, sacudiendo el puño hacia un policía imaginario—, ¡ya verán cómo le doy duro a ese suegro mío!

Y al escucharlo, imaginándose al pobre suegro apaleado, Mini soltaba una carcajada tras otra, a las que su formidable amigo no tardaba en unirse.

Eran mañanas de otoño, la misma época del año en la que, en otros tiempos, los reyes salían a conquistar tierras; y yo, sin moverme jamás de mi pequeño rincón en Calcuta, dejaba que mi mente vagara por todo el mundo. Al escuchar el nombre de otro país, mi corazón se volcaba hacia este, y al ver a un extranjero en las calles, comenzaba a tejer una red de sueños: las montañas, los valles y los bosques de su tierra lejana, con su cabaña en medio del paisaje, y la vida libre e independiente de esos parajes remotos. Quizá esas escenas de viaje se aparecían en mi imaginación con mayor intensidad precisamente porque yo llevaba una vida tan sedentaria, por lo que una invitación a viajar habría caído sobre mí como un rayo.

En presencia de aquel Cabuliwallah, me sentía transportado de inmediato al pie de áridos picos montañosos, con estrechos desfiladeros retorciéndose entre las alturas imponentes. Podía ver la caravana de camellos cargando mercancía, y al grupo de mercaderes con turbante portando sus extrañas armas antiguas y algunas de sus lanzas, descendiendo hacia las llanuras. Lo veía todo… hasta que, en momentos así, la madre de Mini intervenía, suplicándome que “tuviera cuidado con ese hombre”.

La madre de Mini, lamentablemente, es una mujer muy temerosa. Cada vez que oye un ruido en la calle, o ve gente acercándose a la casa, enseguida asume que son ladrones, borrachos, serpientes, tigres, malaria, cucarachas, orugas, o un marinero inglés. A pesar de todos estos años de experiencia, ella no había logrado superar su miedo. Así que vivía llena de sospechas respecto al Cabuliwallah y me pedía con insistencia que lo vigilara bien.

Yo trataba de ahuyentar suavemente sus temores con una risa , pero entonces ella se volvía hacia mí con gesto serio y me lanzaba preguntas solemnes.

—¿Acaso nunca hubo niños secuestrados?

—¿No es cierto que hay esclavitud en Kabul?

—¿Tan absurdo te parece que ese hombre tan grande pueda llevarse a una niña tan pequeña?

Yo le respondía que, aunque no imposible, era bastante improbable. Pero eso no bastaba, y su angustia persistía. Como era una angustia infundada, no me parecía justo prohibirle la entrada al hombre, así que la amistad entre él y Mini continuó sin obstáculos.

Cada año a mediados de enero, Rahmun, el Cabuliwallah, solía regresar a su país y, cuando se acercaba la fecha, andaba muy ocupado yendo de casa en casa cobrando sus deudas. Este año, sin embargo, siempre encontraba tiempo para pasar a ver a Mini. Un observador externo podría tener la impresión de que había una especie de conspiración entre los dos, porque si no venía en la mañana, aparecía por la tarde.

Incluso para mí era un poco desconcertante, de vez en cuando, encontrar repentinamente en el rincón de una habitación oscura a este hombre alto, de ropas sueltas y lleno de bolsas; pero cuando Mini entraba corriendo, sonriente con su «¡Oh, Cabuliwallah! ¡Cabuliwallah!» y los dos amigos, tan distantes en edad, volvían a sus risas y bromas de siempre, me sentía tranquilo.

Una mañana, pocos días antes de que él hubiera decidido partir, estaba corrigiendo mis impresiones de prueba en el estudio. Hacía frío. A través de la ventana, los rayos del sol tocaban mis pies, y ese leve calor era muy bienvenido. Eran casi las ocho y los primeros transeúntes regresaban a casa, con la cabeza cubierta. De pronto, escuché un alboroto en la calle y, al asomarme, vi a Rahmun siendo llevado, atado, entre dos policías, seguidos por un grupo de niños curiosos. Había manchas de sangre en la ropa del Cabuliwallah, y uno de los policías llevaba un cuchillo. Salí apresurado, los detuve y pregunté qué significaba todo eso. Unos me dijeron una cosa, otros otra, y así supe que un vecino le debía dinero al vendedor por un chal Rampuri, pero que falsamente había negado haberle comprado. En medio de la discusión, Rahmun lo había golpeado. Ahora, enardecido, el prisionero empezó a insultar a su enemigo cuando, de pronto, en una de las terrazas de mi casa apareció mi pequeña Mini con su exclamación de siempre:

—¡Oh, Cabuliwallah! ¡Cabuliwallah!

El rostro de Rahmun se iluminó al verla. Ese día no llevaba su bolsa bajo el brazo, así que ella no podía hablar con él del elefante. Entonces pasó a la siguiente pregunta: “¿Vas a casa de tu suegro?” Rahmun rió y dijo:

—¡Justo allá voy, pequeñita!

Luego, al notar que la respuesta no divertía a la niña, levantó sus manos encadenadas.

—¡Ali! —dijo— ¡le habría dado una paliza a ese viejo suegro, pero tengo las manos atadas!

Acusado de agresión con intención de matar, Rahmun fue condenado a varios años de prisión.

El tiempo pasó y él fue olvidado. El trabajo de siempre, en el lugar de siempre que seguía siendo nuestro; y rara vez pensábamos en aquel montañés que antaño fue libre y que ahora pasaba sus años en prisión. Incluso mi alegre Mini, debo confesar con vergüenza, olvidó a su viejo amigo. Nuevas compañías llenaron su vida. Al crecer, pasó más tiempo con otras niñas. Tanto así que ya no venía, como antes, a la habitación de su padre. Casi no hablábamos entre nosotros.

Pasaron los años. Era nuevamente otoño, y habíamos hecho los arreglos para el matrimonio de Mini. Se celebraría durante las vacaciones del Puja. Con el regreso de Durga a Kailas, la luz de nuestro hogar también partiría a la casa de su esposo, dejando a su padre en las sombras.

La mañana era radiante. Tras las lluvias, el aire parecía purificado, y los rayos del sol se veían como oro puro. Tan brillantes eran que daban una belleza especial incluso a los sórdidos muros de ladrillo de nuestras calles de Calcuta. Desde el amanecer, las flautas de boda resonaban, y con cada nota mi corazón latía con más fuerza. El lamento de la melodía Bhairavi parecía intensificar mi dolor ante la inminente separación. Mi Mini se casaría esa misma noche.

Desde temprano, la casa estaba llena de ruido y ajetreo. En el patio, había que colgar el toldo sobre los postes de bambú; los candelabros, con su tintineo, debían instalarse en cada habitación y en la terraza. La prisa y la emoción no tenían fin. Yo estaba sentado en mi estudio, revisando las cuentas, cuando alguien entró, saludó con respeto y se plantó frente a mí. Era Rahmun, el Cabuliwallah. Al principio no lo reconocí. No tenía su bolsa, ni el cabello largo, ni el vigor de antes. Pero al sonreír, lo reconocí.

—¿Cuándo llegaste, Rahmun? —le pregunté.

—Anoche —respondió—, salí de la cárcel.

Sus palabras me chocaron. Nunca había conversado con alguien que hubiese herido a otro y sentí mi corazón encogerse al pensar en eso, como si con su aparición el día tuviese un mal augurio.

—Estamos en medio de las ceremonias —dije—, y estoy ocupado. ¿Podrías venir otro día?

De inmediato se dio la vuelta para irse; pero, al llegar a la puerta, vaciló y dijo:

—¿No podría ver a la niña, señor, por un momento? —Creía que Mini seguía siendo la misma. La imaginaba corriendo hacia él, como antes, diciendo «¡Oh Cabuliwallah! ¡Cabuliwallah!» También creyó que reirían y charlarían como en los viejos tiempos. De hecho, en memoria de aquellos días, traía, cuidadosamente envueltos en papel, unas cuantas almendras, pasas y uvas que había conseguido de algún paisano, ya que su propio fondo se había agotado.

—Hay una ceremonia en casa, y no podrás ver a nadie hoy— repetí.

El rostro del hombre se entristeció. Me miró con nostalgia un momento, dijo «Buen día» y se marchó. Me sentí un poco apenado, y estuve a punto de llamarlo, pero vi que regresaba por su cuenta. Se acercó, extendió sus ofrendas y dijo:

—Traje estas cositas, señor, para la niña. ¿Podría dárselas usted?

Las tomé y me dispuse a pagarle, pero él me detuvo con la mano.

—¡Usted es muy amable, señor! Guárdeme en su recuerdo. ¡No me dé dinero! Usted tiene una hija pequeña; yo también tengo una parecida, allá en mi tierra. Pienso en ella y por eso traigo frutas para su niña, no para lucrarme.

Dicho esto, metió la mano dentro de su gran túnica suelta y sacó un pedazo pequeño y sucio de papel. Con mucho cuidado lo desplegó y lo alisó sobre mi mesa con ambas manos. Llevaba la impresión de una manita. No era una fotografía. Tampoco un dibujo. Era la impresión de una mano untada de tinta, extendida sobre el papel. Ese toque de su pequeña hija lo había llevado siempre en su corazón mientras, año tras año, venía a Calcuta a vender sus mercancías en la calle.

Las lágrimas inundaron mis ojos. Olvidé que él era un pobre vendedor de frutas de Kabul, mientras que yo… pero no, ¿qué era yo más que él? Él también era padre. Esa impresión de la mano de su pequeña Parbati, allá en su lejano hogar montañés, me hizo recordar a mi propia Mini.

Inmediatamente mandé llamar a Mini de los aposentos interiores. Hubo muchas objeciones, pero no las escuché. Vestida con la seda roja de su boda, con la pasta de sándalo en la frente y adornada como una joven novia, Mini vino y se quedó parada, tímida, frente a mí.

El Cabuliwallah se mostró un poco desconcertado ante esa aparición. No pudo revivir su antigua amistad. Finalmente, sonrió y dijo:

—Pequeña, ¿vas a casa de tu suegro?

Pero Mini ahora comprendía el significado de la palabra suegro y ya no pudo responder como antes. Se sonrojó ante la pregunta y permaneció de pie, con la mirada baja y su rostro de novia agachado.

Recordé el día en que el Cabuliwallah y mi Mini se conocieron, y me invadió la tristeza. Cuando ella se fue, Rahmun suspiró profundamente y se sentó en el suelo. De pronto se le ocurrió que su hija también debía haber crecido en todo ese tiempo y que tendría que volver a hacerse amigo de ella. Seguramente ya no la encontraría como la había dejado. Además, ¿qué no habría podido pasarle en esos ocho años?

Sonaban las flautas nupciales y el sol otoñal, suave, se derramaba sobre nosotros. Pero Rahmun, sentado en un callejón de Calcuta, veía ante sí las montañas áridas de Afganistán.

Saqué un billete y se lo entregué.

—Regresa con tu hija, Rahmun, a tu tierra, y que la dicha de ese reencuentro traiga buena fortuna a la mía.

Después de hacer ese regalo, tuve que reducir algunos festejos. No pudimos tener las luces eléctricas que quería, ni la banda militar, y las damas de la casa estaban desanimadas por ello. Pero, para mí, el banquete de bodas fue más brillante al pensar que, en una tierra lejana, un padre ausente por mucho tiempo se reencontraba con su única hija.

Diana Milena Castro Urrea es licenciada en Filología e Idiomas Inglés de la Universidad Nacional de Colombia y profesional en Lenguas Modernas de la Universidad EAN. Traductora, intérprete y correctora de estilo con experiencia en los sectores técnico, jurídico, médico y humanitario. Especializada en traducción literaria, interpretación simultánea y consecutiva, y en la gestión de proyectos multilingües. Actualmente trabaja como traductora e intérprete para la organización The HALO Trust y como traductora independiente. Se ha enfocado en la traducción de textos con un enfoque preciso y culturalmente adaptado, utilizando herramientas avanzadas para garantizar la coherencia y calidad en cada proyecto. Su trabajo refleja un compromiso con la educación, la participación ciudadana y la integración comunitaria a través del multilingüismo.