Bee, bee, la oveja negra (fragmento)

Traducción del inglés por Natasha Besoky

Texto original de Rudyard Kipling

Edición por Daniela Arias

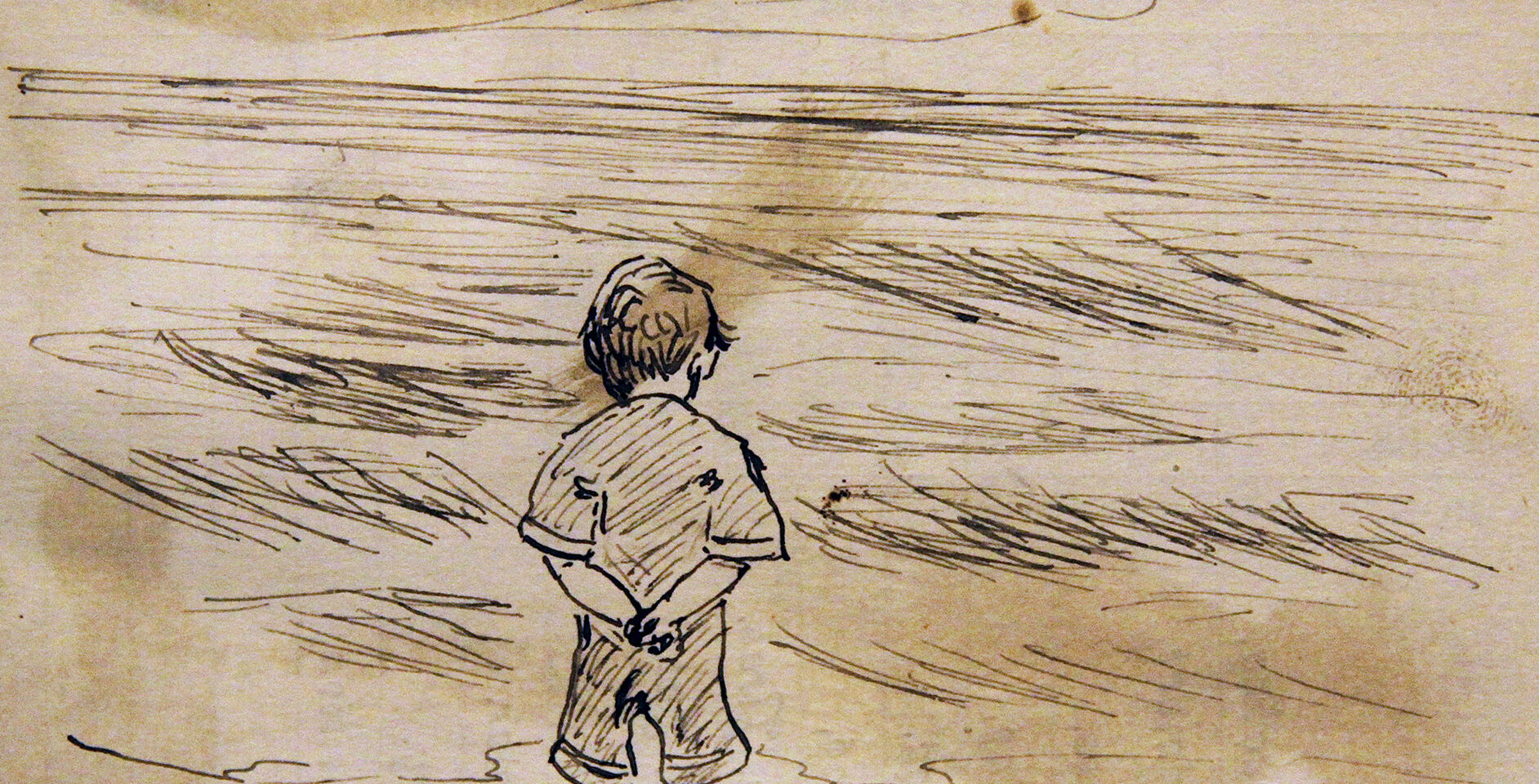

Imagen: «Little boy looking at the sea» de Edward Hopper

Bee, bee, oveja negra

¿Tenés algo de lana hoy?

Sí, señor, sí. Tres bolsas llenas tengo.

Una para el amo, otra para la dama.

Ninguna para el niño que llora en la cama.

Canción infantil

LA PRIMERA BOLSA

“Cuando estaba en la casa de mi padre, estaba en un lugar mejor”.

Era la hora de acostar a Punch: el aya y el hamal, y Meeta, el gran muchacho suratí del turbante dorado y rojo lo acompañaban. Judy, ya arropada dentro de sus cortinas contra mosquitos, estaba casi dormida. A Punch le habían permitido quedarse despierto para la cena. En los últimos diez días, se le habían concedido muchos privilegios, y una mayor amabilidad por parte de la gente de su mundo había envuelto sus hazañas y modales, que en su mayoría eran escandalosos. Se sentó en el borde de la cama y balanceó las piernas desnudas de forma desafiante.

—¿Punch-baba se va a dormir? —dijo el aya con un tono insinuante.

—No —dijo Punch—. Punch-baba quiere escuchar la historia de la rani que se convirtió en tigre. Meeta tiene que contarla, y el hamal tiene que esconderse detrás de la puerta y hacer ruidos de tigre en el momento adecuado.

—Pero Judy-baba se va a despertar —dijo el aya.

—Judy-baba se despertó —dijo una vocecita desde las cortinas contra mosquitos—. Había una vez una rani que vivía en Delhi. Seguí, Meeta. —Y volvió a dormirse mientras Meeta comenzaba a relatar el cuento.

Punch nunca antes había logrado que le contaran esa historia con tan poca resistencia. Reflexionó un buen rato. El hamal hizo ruidos de tigre en veinte tonos diferentes.

—¡Pará! —dijo Punch con tono autoritario—. ¿Por qué no viene papá a decirme que me va a dar un pum-pum?

—Punch-baba se va a marchar pronto —dijo el aya—. Dentro de una semana, no va a estar aquí para tirarme el pelo. —Lanzó un tierno suspiro, porque quería mucho al niño.

—¿En un tren por las Ghats? —dijo Punch, mientras se paraba en la cama—. ¿Hasta llegar a Nasik, donde vive la Rani Tigre?

—Este año no vas a ir a Nasik, pequeño sahib —dijo Meeta, mientras se lo subía al hombro—. Viajarás hasta la costa del mar, donde los cocos se caen, y cruzarás el mar en un barco muy grande. ¿Vas a llevar a Meeta con vos a Belait?

—Todos van a venir —dijo Punch, desde los fuertes brazos de Meeta—. Meeta y el aya y el hamal y el jardinero Bhini, y el salaam capitán sahib, el domador de serpientes.

No había burla en la voz de Meeta cuando respondió «Grande es el favor del sahib», y acostó al pequeño en la cama mientras el aya, sentada a la luz de la luna en el umbral de la puerta, lo arrulló con un cántico interminable, como los que cantan en la Iglesia Católica Romana de Parel. Punch se hizo un ovillo y se durmió.

A la mañana siguiente, Judy anunció a los gritos que había una rata en la habitación, y así fue como Punch se olvidó de contarle las excelentes noticias. No tenía mucha importancia, porque Judy solo tenía tres años y tampoco lo habría entendido. Pero Punch tenía cinco y sabía que ir a Inglaterra sería mucho más lindo que viajar a Nasik.

Papá y mamá vendieron el brougham y el piano, desmantelaron la casa, redujeron la cantidad de vajilla para usarla en las comidas diarias y deliberaron largo y tendido sobre un montón de cartas que llevaban el matasellos de Rocklington.

—Lo peor de todo es que uno no puede estar seguro de nada —dijo papá, retorciéndose el bigote—. Las cartas son excelentes y las condiciones bastante razonables.

«Lo peor de todo es que los niños crecerán lejos de mí», pensó mamá; pero no lo dijo en voz alta.

—No somos más que un caso entre cientos —dijo papá con amargura—. Volverás a casa dentro de cinco años, querida.

—Para entonces Punch tendrá diez años… y Judy ocho. ¡Qué largos, largos, larguísimos serán esos años! Y tendremos que dejarlos con extraños.

—Punch en un niño muy alegre. Estoy seguro de que hará amigos dondequiera que vaya.

—¿Y quién no querría a mi Ju?

Estaban de pie junto a las dos camitas en el cuarto de los niños, tarde en la noche, y creo que mamá lloraba en silencio. Cuando papá se marchó, mamá se arrodilló junto a la cuna de Judy. El aya la vio y rezó para que a la memsahib nunca le arrebataran el amor de sus hijos y se lo entregaran a un extraño.

La oración de mamá era un tanto ilógica. En resumen, decía: «Que esas personas desconocidas amen a mis hijos y sean tan buenas con ellos como yo lo sería, pero que pueda conservar su amor y su confianza para siempre. Amén». Punch se rascó entre sueños, y Judy gimió un poquito. Al parecer, esa fue la única respuesta a la plegaria. Al día siguiente, todos bajaron al mar, y hubo una escena en el Apollo Bunder cuando Punch descubrió que Meeta no podía ir con ellos y Judy comprendió que debían dejar atrás al aya. Pero Punch encontró mil cosas fascinantes en las cuerdas, las poleas y las tuberías de vapor del gran barco de la P&O mucho antes de que Meeta y el aya se hubieran secado las lágrimas.

—Volvé, Punch-baba —dijo el aya.

—Volvé —dijo Meeta—, y convertite en un burra sahib.

—Sí —dijo Punch, mientras su padre lo tenía en brazos y lo levantaba para que se despidiera con la mano—. Sí, voy a volver y entonces voy a ser un burra sahib bahadur.

Cuando el primer día llegó a su fin, Punch pidió que lo dejaran en Inglaterra, convencido de que debían de estar muy cerca. Al día siguiente, una brisa ligera agitó el aire, y Punch se mareó mucho.

—Cuando vuelva a Bombay, —dijo Punch en cuanto se recuperó del mareo—, voy a viajar por tierra en un gharri. Este barco es muy malo.

El contramaestre sueco lo consoló, y Punch fue cambiando de opinión a medida que el barco avanzaba. Había tanto para ver, tocar y preguntar, que prácticamente se había olvidado del aya, de Meeta y del hamal, y apenas recordaba algunas palabras en indostaní, la que alguna vez había sido su segunda lengua.

El caso de Judy era mucho peor. El día anterior a que el barco de vapor llegara a Southampton, mamá le preguntó si no le gustaría volver a ver al aya. Los ojos azules de Judy observaron el inmenso mar que había devorado todo su pequeño pasado, y respondió:

—¿Aya? ¿Qué aya?

Mamá lloró por ella, y Punch se asombró. Fue entonces cuando escuchó por primera vez la apasionada súplica de mamá: «No dejes que Judy se olvide de mamá». Dado que Judy era pequeña, absurdamente pequeña, y que mamá, todas las noches durante las últimas cuatro semanas, había entrado al camarote para arrullarlos con una melodía misteriosa que él llamaba «Mi niño del alma», Punch no podía entender a qué se refería. Pero se esforzó por cumplir su deber, porque en cuanto mamá salió del camarote, le dijo a Judy:

—Ju, ¿te acuerdás de mamá?

—¡Caro que sí! —dijo Judy.

—Entonces siempre acuerdate de mamá, o si no, no te voy a dar los patitos de papel que me regaló el capitán sahib de pelo rojo.

Y Judy prometió que siempre se «acuerdaría» de mamá.

Muchas pero muchas veces, mamá le repetía a Punch la misma súplica, y papá decía lo mismo con una insistencia que asombraba al niño.

—Tenés que aprender a escribir enseguida, Punch —decía papá—, para que puedas enviarnos cartas a Bombay.

—Entraré en tu habitación —dijo Punch, y a papá se le hizo un nudo en la garganta.

Papá y mamá siempre andaban con un nudo en la garganta aquellos días. Si Punch retaba a Judy por no «acuerdarse», se les hacía un nudo en la garganta. Si Punch se tumbaba en el sofá de la pensión en Southampton y dibujaba su futuro en tonos púrpura y dorado, se les hacía un nudo en la garganta; y lo mismo pasaba si Judy acercaba los labios para darles un beso.

Durante varios días, los cuatro fueron unos vagabundos sobre la faz de la tierra: Punch no tenía a quién darle órdenes, Judy era demasiado joven para todo, y papá y mamá estaban serios, distraídos y tenían un nudo en la garganta.

—¿Dónde está? —exigió Punch, harto ya de aquel horrible artefacto de cuatro ruedas que llevaba un montón de valijas encima—. ¿Dónde está nuestro gharri? Esto habla tanto que yo no puedo hablar. ¿Dónde está nuestro gharri? Cuando estaba en Bandstand, antes que nos viniéramos, le pregunté al sahib Inverarity por qué estaba sentado en nuestro gharri, y él me dijo que era suyo. Y yo le dije: «Te lo regalo» —me cae bien el sahib Inverarity—y le dije: «¿Podés meter las piernas por las correas de cuero a través de las ventanas?» Y el sahib Inverarity dijo que no, y se rió. Yo sí que puedo meter las piernas en las correas de cuero. Puedo meter las piernas en estas correas de cuero. ¡Mirá! ¡Uy! ¡Mamá está llorando otra vez! No sabía. No sabía que eso no se hace.

Punch sacó las piernas de las correas de cuero del carruaje de cuatro ruedas: la puerta se abrió y el niño se deslizó hacia el suelo, entre una catarata de paquetes, hasta la puerta de una austera casita de campo, con un cartel en la reja que rezaba «Downe Lodge». Punch se recompuso como pudo y miró la casa con desagrado. Estaba sobre un camino de tierra, y un viento frío le hacía cosquillas en las piernas cubiertas por pantalones bombachos.

—Volvamos —dijo Punch—. Este lugar es feo.

Pero papá y mamá y Judy ya se habían bajado del coche, y los criados estaban entrando todo el equipaje a la casa. En el umbral había una mujer vestida de negro, que sonreía ampliamente con los labios secos y agrietados. Detrás de ella había un hombre, grande, huesudo, canoso y rengo de una pierna, y detrás de él, un niño de doce años, de pelo negro y aspecto grasoso. Punch examinó al trío y se acercó sin miedo, como solía hacer en Bombay cuando alguien visitaba la casa y él estaba jugando en la galería.

—¿Cómo están? —dijo—. Mi nombre es Punch.

Pero todos miraban el equipaje, todos menos el hombre canoso, que le estrechó la mano y le dijo que era “un niño muy avispado”. Había mucho ajetreo y golpes de cajas por todos lados, y Punch se acurrucó en el sofá del comedor y se puso a reflexionar sobre la situación.

—Esta gente no me gusta —dijo Punch—. Pero no importa. Nos vamos a ir enseguida. Siempre nos vamos enseguida de todas partes. Ojalá ya estuviéramos de vuelta en Bombay.

Sus deseos no dieron fruto. Durante seis días, mamá lloró de forma intermitente y le mostró a la mujer de negro toda la ropa de Punch, un atrevimiento que a Punch no le gustó en lo más mínimo. «Aunque a lo mejor es una nueva aya blanca», pensó.

—Tengo que llamarla Tíarosa, pero ella no me dice sahib. Solo me dice Punch —le confió a Judy—. ¿Qué significa Tíarosa?

Judy no lo sabía. Ni ella ni Punch habían oído hablar de un animal que se llamara así. Su mundo se limitaba a papá y mamá, que sabían todo, permitían todo y querían a todo el mundo…incluso a Punch cuando iba al jardín en Bombay y se ensuciaba las uñas de tierra justo después del corte semanal porque, tal como le explicaba a su exhausto padre entre dos zapatillazos, “sentía las puntas de los dedos demasiado nuevas”.

Si bien no sabría decir por qué, a Punch le pareció mejor que sus padres estuvieran entre él y la mujer de negro y el niño de pelo negro. No le caían bien. Le agradaba el hombre canoso, que había expresado su deseo de que lo llamara «Tíoharri». Se saludaban con la cabeza cada vez que se cruzaban, y el hombre canoso le mostró un barquito con jarcias que subían y bajaban.

—Es una maqueta del Brisk; del pequeño Brisk que quedó tan expuesto aquel día en Navarino. —El hombre canoso murmuró esas últimas palabras y cayó en una ensoñación—. Ya te contaré la historia de Navarino, Punch, cuando salgamos a pasear; pero no toques el barco, porque es el Brisk.

Mucho antes de ese paseo, el primero de muchos, despertaron a Punch y Judy una fría madrugada del mes de febrero para decir adiós, entre todas las personas del planeta, a nada menos que a papá y mamá; esta vez los dos lloraban. Punch tenía mucho sueño y Judy estaba de mal humor.

—No se olviden de nosotros —les suplicó mamá—. Hijito mío, no te olvides de nosotros, y no dejes que Judy se olvide.

—Ya le dije a Judy que se acuerdara —dijo Punch, retorciéndose, porque la barba de su padre le hacía cosquillas en el cuello—. Le dije a Judy, diez, cuarenta, quichicientas veces. Pero Ju es muy chiquita; es casi una bebé, ¿no?

—Sí —dijo papá—, es casi una bebé, y vos tenés que ser bueno con ella, y hacer que aprenda a escribir y…y…

Punch volvió a su cama. Judy dormía profundamente, y abajo se escuchaba el traqueteo de un coche. Papá y mamá se habían marchado. No a Nasik; eso quedaba del otro lado del mar. A algún lugar mucho más cercano, por supuesto, y también, por supuesto, volverían. Volverían después de una fiesta, y papá volvería después de ir a un sitio llamado «Las Nieves», y mamá volvería con él, volverían con Punch y con Judy a casa de la señora Inverarity en Marine Lines. Seguro que volvían. Por eso Punch se volvió a dormir hasta bien entrada la mañana, cuando el niño de pelo negro lo recibió con la noticia de que papá y mamá se habían ido a Bombay, y Judy y Punch se quedarían en Downe Lodge «para siempre». Cuando, entre lágrimas, le pidió a Tíarosa que desmintiera las palabras del niño, ella se limitó a decir que Harry había dicho la verdad y que Punch tenía que doblar bien su ropa ante de irse a dormir. Punch salió y lloró con amargura junto a Judy, en cuya cabecita rubia había logrado inculcar cierta idea sobre lo que significaba la separación.

Cuando un hombre maduro descubre que ha sido abandonado por la Providencia, privado de su Dios y arrojado, sin ayuda, consuelo ni empatía a un mundo que le resulta nuevo y extraño, su desesperación —que puede reflejarse en una vida disoluta, en la escritura de sus experiencias o en la más satisfactoria distracción del suicidio— suele considerarse como algo impresionante. Un niño, en idénticas circunstancias, según lo que llega a entender, no puede insultar a Dios y morir. Llora hasta que se le enrojece la nariz, le arden los ojos y le duele la cabeza. Punch y Judy, sin tener ningún tipo de culpa, habían perdido su mundo entero. Se sentaron a llorar en el vestíbulo; el niño de pelo negro los miraba desde lejos.

La maqueta del barco no sirvió de nada, aunque el hombre canoso le asegurara a Punch que podía subir y bajar las jarcias tanto como quisiera; y a Judy se le prometiera libre acceso a la cocina. Ellos querían a papá y mamá, que se habían ido a Bombay, más allá del mar, y la pena que sentían no tuvo consuelo mientras duró.

Cuando las lágrimas cesaron, la casa se sumió en un silencio profundo. Tíarosa había decidido que lo mejor era dejar que «se desahogaran», y el niño se había ido a la escuela. Punch levantó la cabeza del suelo y soltó un respiro con tristeza. Judy estaba casi dormida. Sus tres cortos años aún no le habían enseñado a soportar el dolor con plena conciencia. Se oía un estruendo sordo y lejano… un golpe pesado que se repetía. Punch sabía que había escuchado ese sonido en Bombay, en la temporada del monzón. Era el mar… el mar que había que atravesar antes de poder llegar a Bombay.

—¡Vamos, Ju! —le gritó—. Estamos cerca del mar. ¡Puedo oírlo! ¡Escuchá! Ahí es adonde se fueron. A lo mejor los alcanzamos si llegamos a tiempo. No querían irse sin nosotros. Solo se olvidaron.

—Sí —dijo Judy—. Solo se olviraron. Vamo’ al mar.

La puerta del vestíbulo estaba abierta y también la del jardín.

—Es muy, muy grande este lugar —dijo Punch, mientras miraba el camino con recelo—. Nos vamos a perder, pero encontraré a un hombre y le diré que me lleve de vuelta a mi casa, como hacía en Bombay.

Tomó a Judy de la mano, y los dos huyeron sin sombrero en dirección al sonido del mar. Downe Lodge era casi la última de una fila de casas recién construidas que se extendían, entre un caos de ladrillos, hacia un páramo donde a veces acampaban los gitanos y donde practicaba la guarnición de artillería de Rocklington. No se veía mucha gente, y es probable que confundieran a los niños con los hijos de los soldados, que solían recorrer grandes distancias. Durante media hora, las piernitas agotadas caminaron por el páramo, el campo de papas y las dunas de arena.

—’Toy muy tansada —dijo Judy—, y mamá se va nojá.

—Mamá munca se enoja. Supongo que ahora está esperándonos en el mar mientras papá compra los boletos. Los vamos a encontrar y nos iremos con ellos. Ju, no te sientes. Un poco más y llegamos al mar. Ju, ¡si te sentás, te pego! —dijo Punch.

Subieron otra duna y llegaron hasta el extenso mar gris, con la marea baja. Cientos de cangrejos correteaban por la playa, pero no había ni rastro de papá y mamá, tampoco de un barco en el agua…no había nada más que arena y barro a lo largo de kilómetros y kilómetros.

Y Tíoharri los encontró de casualidad, muy embarrados y muy desamparados; Punch se deshacía en llanto, pero intentaba entretener a Judy con un «grangrecito» y Judy gritaba «¡Mamá! ¡Mamá!» mientras lloraba y miraba hacia el horizonte implacable… «¡Mamá!»

Baa, Baa, Black Sheep,

Have you any wool?

Yes, Sir; yes, Sir; three bags full.

One for the Master, one for the Dame—

None for the Little Boy that cries down the lane.

—Nursery Rhyme.

THE FIRST BAG

“When I was in my father’s house, I was in a better place.”

They were putting Punch to bed–the ayah and the hamal, and Meeta, the big Surti boy with the red and gold turban. Judy, already tucked inside her mosquito-curtains, was nearly asleep. Punch had been allowed to stay up for dinner. Many privileges had been accorded to Punch within the last ten days, and a greater kindness from the people of his world had encompassed his ways and works, which were mostly obstreperous. He sat on the edge of his bed and swung his bare legs defiantly.

“Punch-baba going to bye-lo?” said the ayah suggestively.

“No,” said Punch. “Punch-baba wants the story about the Ranee that was turned into a tiger. Meeta must tell it, and the hamal shall hide behind the door and make tiger-noises at the proper time.”

“But Judy-Baba will wake up,” said the ayah.

“Judy-baba is waking,” piped a small voice from the mosquito-curtains. “There was a Ranee that lived at Delhi. Go on, Meeta,” and she fell asleep again while Meeta began the story.

Never had Punch secured the telling of that tale with so little opposition. He reflected for a long time. The hamal made the tiger-noises in twenty different keys.

“‘Top!” said Punch authoritatively. “Why doesn’t Papa come in and say he is going to give me put-put?”

“Punch-baba is going away,” said the ayah. “In another week there will be no Punch-baba to pull my hair anymore.” She sighed softly, for the boy of the household was very dear to her heart.

“Up the Ghauts in a train?” said Punch, standing on his bed. “All the way to Nassick, where the Ranee-Tiger lives?”

“Not to Nassick this year, little Sahib,” said Meeta, lifting him on his shoulder. “Down to the sea where the cocoanuts are thrown, and across the sea in a big ship. Will you take Meeta with you to Belait?”

“You shall all come,” said Punch, from the height of Meeta’s strong arms. “Meeta and the ayah and the hamal and Bhini-in-the-Garden, and the salaam-Captain-Sahib-snake-man.”

There was no mockery in Meeta’s voice when he replied– “Great is the Sahib’s favour,” and laid the little man down in the bed, while the ayah, sitting in the moonlight at the doorway, lulled him to sleep with an interminable canticle such as they sing in the Roman Catholic Church at Parel. Punch curled himself into a ball and slept.

Next morning Judy shouted that there was a rat in the nursery, and thus he forgot to tell her the wonderful news. It did not much matter, for Judy was only three and she would not have understood. But Punch was five; and he knew that going to England would be much nicer than a trip to Nassick.

And Papa and Mamma sold the brougham and the piano, and stripped the house, and curtailed the allowance of crockery for the daily meals, and took long council together over a bundle of letters bearing the Rocklington postmark.

“The worst of it is that one can’t be certain of anything,” said Papa, pulling his moustache. “The letters in themselves are excellent, and the terms are moderate enough.”

“The worst of it is that the children will grow up away from me,” thought Mamma; but she did not say it aloud.

“We are only one case among hundreds,” said Papa bitterly. “You shall go home again in five years, dear.”

“Punch will be ten then–and Judy eight. Oh, how long and long and long the time will be! And we have to leave them among strangers.”

“Punch is a cheery little chap. He’s sure to make friends wherever he goes.”

“And who could help loving my Ju?”

They were standing over the cots in the nursery late at night, and I think that Mamma was crying softly. After Papa had gone away, she knelt down by the side of Judy’s cot. The ayah saw her and put up a prayer that the memsahib might never find the love of her children taken away from her and given to a stranger.

Mamma’s own prayer was a slightly illogical one. Summarized it ran: “Let strangers love my children and be as good to them as I should be, but let me preserve their love and their confidence for ever and ever. Amen.” Punch scratched himself in his sleep, and Judy moaned a little. That seems to be the only answer to the prayer: and, next day, they all went down to the sea, and there was a scene at the Apollo Bunder when Punch discovered that Meeta could not come too, and Judy learned that the ayah must be left behind. But Punch found a thousand fascinating things in the rope, block, and steam-pipe line on the big P. and O. Steamer, long before Meeta and the ayah had dried their tears.

“Come back, Punch-baba,” said the ayah.

“Come back,” said Meeta, “and be a Burra Sahib.”

“Yes,” said Punch, lifted up in his father’s arms to wave good-bye. “Yes, I will come back, and I will be a Burra Sahib Bahadur!”

At the end of the first day Punch demanded to be set down in England, which he was certain must be close at hand. Next day there was a merry breeze, and Punch was very sick. “When I come back to Bombay,” said Punch on his recovery, “I will come by the road—in a broom-gharri. This is a very naughty ship.”

The Swedish boatswain consoled him, and he modified his opinions as the voyage went on. There was so much to see and to handle and ask questions about that Punch nearly forgot the ayah and Meeta and the hamal, and with difficulty remembered a few words of the Hindustani once his second-speech.

But Judy was much worse. The day before the steamer reached Southampton, Mamma asked her if she would not like to see the ayah again. Judy’s blue eyes turned to the stretch of sea that had swallowed all her tiny past, and she said: “Ayah! What ayah?”

Mamma cried over her, and Punch marveled. It was then that he heard for the first time Mamma’s passionate appeal to him never to let Judy forget Mamma. Seeing that Judy was young, ridiculously young, and that Mamma, every evening for four weeks past, had come into the cabin to sing her and Punch to sleep with a mysterious tune that he called “Sonny, my soul,” Punch could not understand what Mamma meant. But he strove to do his duty, for the moment Mamma left the cabin, he said to Judy: “Ju, you bemember Mamma?”

“’Torse I do,” said Judy.

“Then always bemember Mamma, ’r else I won’t give you the paper ducks that the red-haired Captain Sahib cut out for me.”

So Judy promised always to “bemember Mamma.”

Many and many a time was Mamma’s command laid upon Punch, and Papa would say the same thing with an insistence that awed the child.

“You must make haste and learn to write, Punch,” said Papa, “and then you’ll be able to write letters to us in Bombay.”

“I’ll come into your room,” said Punch, and Papa choked.

Papa and Mamma were always choking in those days. If Punch took Judy to task for not “bemembering,” they choked. If Punch sprawled on the sofa in the Southampton lodging-house and sketched his future in purple and gold, they choked; and so they did if Judy put up her mouth for a kiss.

Through many days all four were vagabonds on the face of the earth: Punch with no one to give orders to, Judy too young for anything, and Papa and Mamma grave, distracted, and choking.

“Where,” demanded Punch, wearied of a loathsome contrivance on four wheels with a mound of luggage atop— “where is our broom-gharri? This thing talks so much that I can’t talk. Where is our own broom-gharri? When I was at Bandstand before we comed away, I asked Inverarity Sahib why he was sitting in it, and he said it was his own. And I said, ‘I will give it you’—I like Inverarity Sahib—and I said, ‘Can you put your legs through the pully-wag loops by the windows? And Inverarity Sahib said No, and laughed. I can put my legs through the pully-wag loops. I can put my legs through these pully-wag loops. Look! Oh, Mamma’s crying again! I didn’t know. I wasn’t not to do so.”

Punch drew his legs out of the loops of the four-wheeler: the door opened and he slid to the earth, in a cascade of parcels, at the door of an austere little villa whose gates bore the legend “Downe Lodge.” Punch gathered himself together and eyed the house with disfavour. It stood on a sandy road, and a cold wind tickled his knickerbockered legs.

“Let us go away,” said Punch. “This is not a pretty place.”

But Mamma and Papa and Judy had quitted the cab, and all the luggage was being taken into the house. At the door-step stood a woman in black, and she smiled largely, with dry chapped lips. Behind her was a man, big, bony, gray, and lame as to one leg—behind him a boy of twelve, black-haired and oily in appearance. Punch surveyed the trio, and advanced without fear, as he had been accustomed to do in Bombay when callers came and he happened to be playing in the veranda.

“How do you do?” said he. “I am Punch.” But they were all looking at the luggage—all except the gray man, who shook hands with Punch and said he was a “smart little fellow.” There was much running about and banging of boxes, and Punch curled himself up on the sofa in the dining-room and considered things.

“I don’t like these people,” said Punch. “But never mind. We’ll go away soon. We have always went away soon from everywhere. I wish we was gone back to Bombay soon.”

The wish bore no fruit. For six days Mamma wept at intervals, and showed the woman in black all Punch’s clothes—a liberty which Punch resented. “But p’raps she’s a new white ayah,” he thought. “I’m to call her Antirosa, but she doesn’t call me Sahib. She says just Punch,” he confided to Judy. “What is Antirosa?”

Judy didn’t know. Neither she nor Punch had heard anything of an animal called an aunt. Their world had been Papa and Mamma, who knew everything, permitted everything, and loved everybody—even Punch when he used to go into the garden at Bombay and fill his nails with mold after the weekly nail-cutting, because, as he explained between two strokes of the slipper to his sorely tried Father, his fingers “felt so new at the ends.”

In an undefined way Punch judged it advisable to keep both parents between himself and the woman in black and the boy in black hair. He did not approve of them. He liked the gray man, who had expressed a wish to be called “Uncleharri.” They nodded at each other when they met, and the gray man showed him a little ship with rigging that took up and down.

“She is a model of the Brisk—the little Brisk that was sore exposed that day at Navarino.” The gray man hummed the last words and fell into a reverie. “I’ll tell you about Navarino, Punch, when we go for walks together; and you mustn’t touch the ship, because she’s the Brisk.”

Long before that walk, the first of many, was taken, they roused Punch and Judy in the chill dawn of a February morning to say Good-bye; and of all people in the wide earth to Papa and Mamma—both crying this time. Punch was very sleepy and Judy was cross.

“Don’t forget us,” pleaded Mamma. “Oh, my little son, don’t forget us, and see that Judy remembers too.”

“I’ve told Judy to bemember,” said Punch, wiggling, for his father’s beard tickled his neck. “I’ve told Judy—ten—forty—’leven thousand times. But Ju’s so young—quite a baby—isn’t she?”

“Yes,” said Papa, “Quite a baby, and you must be good to Judy, and make haste to learn to write and—and—and——”

Punch was back in his bed again. Judy was fast asleep, and there was the rattle of a cab below. Papa and Mamma had gone away. Not to Nassick; that was across the sea. To some place much nearer, of course, and equally of course they would return. They came back after dinner-parties, and Papa had come back after he had been to a place called “The Snows,” and Mamma with him, to Punch and Judy at Mrs. Inverarity’s house in Marine Lines. Assuredly they would come back again. So Punch fell asleep till the true morning, when the black-haired boy met him with the information that Papa and Mamma had gone to Bombay, and that he and Judy were to stay at Downe Lodge “forever.” Antirosa, tearfully appealed to for a contradiction, said that Harry had spoken the truth, and that it behooved Punch to fold up his clothes neatly on going to bed. Punch went out and wept bitterly with Judy, into whose fair head he had driven some ideas of the meaning of separation.

When a matured man discovers that he has been deserted by Providence, deprived of his God, and cast without help, comfort, or sympathy, upon a world which is new and strange to him, his despair, which may find expression in evil-living, the writing of his experiences, or the more satisfactory diversion of suicide, is generally supposed to be impressive. A child, under exactly similar circumstances as far as its knowledge goes, cannot very well curse God and die. It howls till its nose is red, its eyes are sore, and its head aches. Punch and Judy, through no fault of their own, had lost all their world. They sat in the hall and cried; the black-haired boy looking on from afar.

The model of the ship availed nothing, though the gray man assured Punch that he might pull the rigging up and down as much as he pleased; and Judy was promised free entry into the kitchen. They wanted Papa and Mamma, gone to Bombay beyond the seas, and their grief while it lasted was without remedy.

When the tears ceased the house was very still. Antirosa had decided it was better to let the children “have their cry out,” and the boy had gone to school. Punch raised his head from the floor and sniffed mournfully. Judy was nearly asleep. Three short years had not taught her how to bear sorrow with full knowledge. There was a distant, dull boom in the air—a repeated heavy thud. Punch knew that sound in Bombay in the Monsoon. It was the sea—the sea that must be traversed before anyone could get to Bombay.

“Quick, Ju!” he cried, “we’re close to the sea. I can hear it! Listen! That’s where they’ve went. P’raps we can catch them if we was in time. They didn’t mean to go without us. They’ve only forgot.”

“Iss,” said Judy. “They’ve only forgotted. Less go to the sea.”

The hall-door was open and so was the garden-gate.

“It’s very, very big, this place,” he said, looking cautiously down the road, “and we will get lost; but I will find a man and order him to take me back to my house—like I did in Bombay.”

He took Judy by the hand, and the two fled hatless in the direction of the sound of the sea. Downe Villa was almost the last of a range of newly built houses running out, through a chaos of brick-mounds, to a heath where gypsies occasionally camped and where the Garrison Artillery of Rocklington practised. There were few people to be seen, and the children might have been taken for those of the soldiery, who ranged far. Half an hour the wearied little legs tramped across heath, potato-field, and sand-dune.

“I’se so tired,” said Judy, “and Mamma will be angry.”

“Mamma’s never angry. I suppose she is waiting at the sea now while Papa gets tickets. We’ll find them and go along with them. Ju, you mustn’t sit down. Only a little more and we’ll come to the sea. Ju, if you sit down I’ll thmack you!” said Punch.

They climbed another dune, and came upon the great gray sea at low tide. Hundreds of crabs were scuttling about the beach, but there was no trace of Papa and Mamma not even of a ship upon the waters—nothing but sand and mud for miles and miles.

And “Uncleharri” found them by chance—very muddy and very forlorn—Punch dissolved in tears, but trying to divert Judy with an “ickle trab,” and Judy wailing to the pitiless horizon for “Mamma, Mamma!”—and again “Mamma!”

Baa, Baa, Black Sheep,

Have you any wool?

Yes, Sir; yes, Sir; three bags full.

One for the Master, one for the Dame—

None for the Little Boy that cries down the lane.

—Nursery Rhyme.

THE FIRST BAG

“When I was in my father’s house, I was in a better place.”

They were putting Punch to bed–the ayah and the hamal, and Meeta, the big Surti boy with the red and gold turban. Judy, already tucked inside her mosquito-curtains, was nearly asleep. Punch had been allowed to stay up for dinner. Many privileges had been accorded to Punch within the last ten days, and a greater kindness from the people of his world had encompassed his ways and works, which were mostly obstreperous. He sat on the edge of his bed and swung his bare legs defiantly.

“Punch-baba going to bye-lo?” said the ayah suggestively.

“No,” said Punch. “Punch-baba wants the story about the Ranee that was turned into a tiger. Meeta must tell it, and the hamal shall hide behind the door and make tiger-noises at the proper time.”

“But Judy-Baba will wake up,” said the ayah.

“Judy-baba is waking,” piped a small voice from the mosquito-curtains. “There was a Ranee that lived at Delhi. Go on, Meeta,” and she fell asleep again while Meeta began the story.

Never had Punch secured the telling of that tale with so little opposition. He reflected for a long time. The hamal made the tiger-noises in twenty different keys.

“‘Top!” said Punch authoritatively. “Why doesn’t Papa come in and say he is going to give me put-put?”

“Punch-baba is going away,” said the ayah. “In another week there will be no Punch-baba to pull my hair anymore.” She sighed softly, for the boy of the household was very dear to her heart.

“Up the Ghauts in a train?” said Punch, standing on his bed. “All the way to Nassick, where the Ranee-Tiger lives?”

“Not to Nassick this year, little Sahib,” said Meeta, lifting him on his shoulder. “Down to the sea where the cocoanuts are thrown, and across the sea in a big ship. Will you take Meeta with you to Belait?”

“You shall all come,” said Punch, from the height of Meeta’s strong arms. “Meeta and the ayah and the hamal and Bhini-in-the-Garden, and the salaam-Captain-Sahib-snake-man.”

There was no mockery in Meeta’s voice when he replied– “Great is the Sahib’s favour,” and laid the little man down in the bed, while the ayah, sitting in the moonlight at the doorway, lulled him to sleep with an interminable canticle such as they sing in the Roman Catholic Church at Parel. Punch curled himself into a ball and slept.

Next morning Judy shouted that there was a rat in the nursery, and thus he forgot to tell her the wonderful news. It did not much matter, for Judy was only three and she would not have understood. But Punch was five; and he knew that going to England would be much nicer than a trip to Nassick.

And Papa and Mamma sold the brougham and the piano, and stripped the house, and curtailed the allowance of crockery for the daily meals, and took long council together over a bundle of letters bearing the Rocklington postmark.

“The worst of it is that one can’t be certain of anything,” said Papa, pulling his moustache. “The letters in themselves are excellent, and the terms are moderate enough.”

“The worst of it is that the children will grow up away from me,” thought Mamma; but she did not say it aloud.

“We are only one case among hundreds,” said Papa bitterly. “You shall go home again in five years, dear.”

“Punch will be ten then–and Judy eight. Oh, how long and long and long the time will be! And we have to leave them among strangers.”

“Punch is a cheery little chap. He’s sure to make friends wherever he goes.”

“And who could help loving my Ju?”

They were standing over the cots in the nursery late at night, and I think that Mamma was crying softly. After Papa had gone away, she knelt down by the side of Judy’s cot. The ayah saw her and put up a prayer that the memsahib might never find the love of her children taken away from her and given to a stranger.

Mamma’s own prayer was a slightly illogical one. Summarized it ran: “Let strangers love my children and be as good to them as I should be, but let me preserve their love and their confidence for ever and ever. Amen.” Punch scratched himself in his sleep, and Judy moaned a little. That seems to be the only answer to the prayer: and, next day, they all went down to the sea, and there was a scene at the Apollo Bunder when Punch discovered that Meeta could not come too, and Judy learned that the ayah must be left behind. But Punch found a thousand fascinating things in the rope, block, and steam-pipe line on the big P. and O. Steamer, long before Meeta and the ayah had dried their tears.

“Come back, Punch-baba,” said the ayah.

“Come back,” said Meeta, “and be a Burra Sahib.”

“Yes,” said Punch, lifted up in his father’s arms to wave good-bye. “Yes, I will come back, and I will be a Burra Sahib Bahadur!”

At the end of the first day Punch demanded to be set down in England, which he was certain must be close at hand. Next day there was a merry breeze, and Punch was very sick. “When I come back to Bombay,” said Punch on his recovery, “I will come by the road—in a broom-gharri. This is a very naughty ship.”

The Swedish boatswain consoled him, and he modified his opinions as the voyage went on. There was so much to see and to handle and ask questions about that Punch nearly forgot the ayah and Meeta and the hamal, and with difficulty remembered a few words of the Hindustani once his second-speech.

But Judy was much worse. The day before the steamer reached Southampton, Mamma asked her if she would not like to see the ayah again. Judy’s blue eyes turned to the stretch of sea that had swallowed all her tiny past, and she said: “Ayah! What ayah?”

Mamma cried over her, and Punch marveled. It was then that he heard for the first time Mamma’s passionate appeal to him never to let Judy forget Mamma. Seeing that Judy was young, ridiculously young, and that Mamma, every evening for four weeks past, had come into the cabin to sing her and Punch to sleep with a mysterious tune that he called “Sonny, my soul,” Punch could not understand what Mamma meant. But he strove to do his duty, for the moment Mamma left the cabin, he said to Judy: “Ju, you bemember Mamma?”

“’Torse I do,” said Judy.

“Then always bemember Mamma, ’r else I won’t give you the paper ducks that the red-haired Captain Sahib cut out for me.”

So Judy promised always to “bemember Mamma.”

Many and many a time was Mamma’s command laid upon Punch, and Papa would say the same thing with an insistence that awed the child.

“You must make haste and learn to write, Punch,” said Papa, “and then you’ll be able to write letters to us in Bombay.”

“I’ll come into your room,” said Punch, and Papa choked.

Papa and Mamma were always choking in those days. If Punch took Judy to task for not “bemembering,” they choked. If Punch sprawled on the sofa in the Southampton lodging-house and sketched his future in purple and gold, they choked; and so they did if Judy put up her mouth for a kiss.

Through many days all four were vagabonds on the face of the earth: Punch with no one to give orders to, Judy too young for anything, and Papa and Mamma grave, distracted, and choking.

“Where,” demanded Punch, wearied of a loathsome contrivance on four wheels with a mound of luggage atop— “where is our broom-gharri? This thing talks so much that I can’t talk. Where is our own broom-gharri? When I was at Bandstand before we comed away, I asked Inverarity Sahib why he was sitting in it, and he said it was his own. And I said, ‘I will give it you’—I like Inverarity Sahib—and I said, ‘Can you put your legs through the pully-wag loops by the windows? And Inverarity Sahib said No, and laughed. I can put my legs through the pully-wag loops. I can put my legs through these pully-wag loops. Look! Oh, Mamma’s crying again! I didn’t know. I wasn’t not to do so.”

Punch drew his legs out of the loops of the four-wheeler: the door opened and he slid to the earth, in a cascade of parcels, at the door of an austere little villa whose gates bore the legend “Downe Lodge.” Punch gathered himself together and eyed the house with disfavour. It stood on a sandy road, and a cold wind tickled his knickerbockered legs.

“Let us go away,” said Punch. “This is not a pretty place.”

But Mamma and Papa and Judy had quitted the cab, and all the luggage was being taken into the house. At the door-step stood a woman in black, and she smiled largely, with dry chapped lips. Behind her was a man, big, bony, gray, and lame as to one leg—behind him a boy of twelve, black-haired and oily in appearance. Punch surveyed the trio, and advanced without fear, as he had been accustomed to do in Bombay when callers came and he happened to be playing in the veranda.

“How do you do?” said he. “I am Punch.” But they were all looking at the luggage—all except the gray man, who shook hands with Punch and said he was a “smart little fellow.” There was much running about and banging of boxes, and Punch curled himself up on the sofa in the dining-room and considered things.

“I don’t like these people,” said Punch. “But never mind. We’ll go away soon. We have always went away soon from everywhere. I wish we was gone back to Bombay soon.”

The wish bore no fruit. For six days Mamma wept at intervals, and showed the woman in black all Punch’s clothes—a liberty which Punch resented. “But p’raps she’s a new white ayah,” he thought. “I’m to call her Antirosa, but she doesn’t call me Sahib. She says just Punch,” he confided to Judy. “What is Antirosa?”

Judy didn’t know. Neither she nor Punch had heard anything of an animal called an aunt. Their world had been Papa and Mamma, who knew everything, permitted everything, and loved everybody—even Punch when he used to go into the garden at Bombay and fill his nails with mold after the weekly nail-cutting, because, as he explained between two strokes of the slipper to his sorely tried Father, his fingers “felt so new at the ends.”

In an undefined way Punch judged it advisable to keep both parents between himself and the woman in black and the boy in black hair. He did not approve of them. He liked the gray man, who had expressed a wish to be called “Uncleharri.” They nodded at each other when they met, and the gray man showed him a little ship with rigging that took up and down.

“She is a model of the Brisk—the little Brisk that was sore exposed that day at Navarino.” The gray man hummed the last words and fell into a reverie. “I’ll tell you about Navarino, Punch, when we go for walks together; and you mustn’t touch the ship, because she’s the Brisk.”

Long before that walk, the first of many, was taken, they roused Punch and Judy in the chill dawn of a February morning to say Good-bye; and of all people in the wide earth to Papa and Mamma—both crying this time. Punch was very sleepy and Judy was cross.

“Don’t forget us,” pleaded Mamma. “Oh, my little son, don’t forget us, and see that Judy remembers too.”

“I’ve told Judy to bemember,” said Punch, wiggling, for his father’s beard tickled his neck. “I’ve told Judy—ten—forty—’leven thousand times. But Ju’s so young—quite a baby—isn’t she?”

“Yes,” said Papa, “Quite a baby, and you must be good to Judy, and make haste to learn to write and—and—and——”

Punch was back in his bed again. Judy was fast asleep, and there was the rattle of a cab below. Papa and Mamma had gone away. Not to Nassick; that was across the sea. To some place much nearer, of course, and equally of course they would return. They came back after dinner-parties, and Papa had come back after he had been to a place called “The Snows,” and Mamma with him, to Punch and Judy at Mrs. Inverarity’s house in Marine Lines. Assuredly they would come back again. So Punch fell asleep till the true morning, when the black-haired boy met him with the information that Papa and Mamma had gone to Bombay, and that he and Judy were to stay at Downe Lodge “forever.” Antirosa, tearfully appealed to for a contradiction, said that Harry had spoken the truth, and that it behooved Punch to fold up his clothes neatly on going to bed. Punch went out and wept bitterly with Judy, into whose fair head he had driven some ideas of the meaning of separation.

When a matured man discovers that he has been deserted by Providence, deprived of his God, and cast without help, comfort, or sympathy, upon a world which is new and strange to him, his despair, which may find expression in evil-living, the writing of his experiences, or the more satisfactory diversion of suicide, is generally supposed to be impressive. A child, under exactly similar circumstances as far as its knowledge goes, cannot very well curse God and die. It howls till its nose is red, its eyes are sore, and its head aches. Punch and Judy, through no fault of their own, had lost all their world. They sat in the hall and cried; the black-haired boy looking on from afar.

The model of the ship availed nothing, though the gray man assured Punch that he might pull the rigging up and down as much as he pleased; and Judy was promised free entry into the kitchen. They wanted Papa and Mamma, gone to Bombay beyond the seas, and their grief while it lasted was without remedy.

When the tears ceased the house was very still. Antirosa had decided it was better to let the children “have their cry out,” and the boy had gone to school. Punch raised his head from the floor and sniffed mournfully. Judy was nearly asleep. Three short years had not taught her how to bear sorrow with full knowledge. There was a distant, dull boom in the air—a repeated heavy thud. Punch knew that sound in Bombay in the Monsoon. It was the sea—the sea that must be traversed before anyone could get to Bombay.

“Quick, Ju!” he cried, “we’re close to the sea. I can hear it! Listen! That’s where they’ve went. P’raps we can catch them if we was in time. They didn’t mean to go without us. They’ve only forgot.”

“Iss,” said Judy. “They’ve only forgotted. Less go to the sea.”

The hall-door was open and so was the garden-gate.

“It’s very, very big, this place,” he said, looking cautiously down the road, “and we will get lost; but I will find a man and order him to take me back to my house—like I did in Bombay.”

He took Judy by the hand, and the two fled hatless in the direction of the sound of the sea. Downe Villa was almost the last of a range of newly built houses running out, through a chaos of brick-mounds, to a heath where gypsies occasionally camped and where the Garrison Artillery of Rocklington practised. There were few people to be seen, and the children might have been taken for those of the soldiery, who ranged far. Half an hour the wearied little legs tramped across heath, potato-field, and sand-dune.

“I’se so tired,” said Judy, “and Mamma will be angry.”

“Mamma’s never angry. I suppose she is waiting at the sea now while Papa gets tickets. We’ll find them and go along with them. Ju, you mustn’t sit down. Only a little more and we’ll come to the sea. Ju, if you sit down I’ll thmack you!” said Punch.

They climbed another dune, and came upon the great gray sea at low tide. Hundreds of crabs were scuttling about the beach, but there was no trace of Papa and Mamma not even of a ship upon the waters—nothing but sand and mud for miles and miles.

And “Uncleharri” found them by chance—very muddy and very forlorn—Punch dissolved in tears, but trying to divert Judy with an “ickle trab,” and Judy wailing to the pitiless horizon for “Mamma, Mamma!”—and again “Mamma!”

Bee, bee, oveja negra

¿Tenés algo de lana hoy?

Sí, señor, sí. Tres bolsas llenas tengo.

Una para el amo, otra para la dama.

Ninguna para el niño que llora en la cama.

Canción infantil

LA PRIMERA BOLSA

“Cuando estaba en la casa de mi padre, estaba en un lugar mejor”.

Era la hora de acostar a Punch: el aya y el hamal, y Meeta, el gran muchacho suratí del turbante dorado y rojo lo acompañaban. Judy, ya arropada dentro de sus cortinas contra mosquitos, estaba casi dormida. A Punch le habían permitido quedarse despierto para la cena. En los últimos diez días, se le habían concedido muchos privilegios, y una mayor amabilidad por parte de la gente de su mundo había envuelto sus hazañas y modales, que en su mayoría eran escandalosos. Se sentó en el borde de la cama y balanceó las piernas desnudas de forma desafiante.

—¿Punch-baba se va a dormir? —dijo el aya con un tono insinuante.

—No —dijo Punch—. Punch-baba quiere escuchar la historia de la rani que se convirtió en tigre. Meeta tiene que contarla, y el hamal tiene que esconderse detrás de la puerta y hacer ruidos de tigre en el momento adecuado.

—Pero Judy-baba se va a despertar —dijo el aya.

—Judy-baba se despertó —dijo una vocecita desde las cortinas contra mosquitos—. Había una vez una rani que vivía en Delhi. Seguí, Meeta. —Y volvió a dormirse mientras Meeta comenzaba a relatar el cuento.

Punch nunca antes había logrado que le contaran esa historia con tan poca resistencia. Reflexionó un buen rato. El hamal hizo ruidos de tigre en veinte tonos diferentes.

—¡Pará! —dijo Punch con tono autoritario—. ¿Por qué no viene papá a decirme que me va a dar un pum-pum?

—Punch-baba se va a marchar pronto —dijo el aya—. Dentro de una semana, no va a estar aquí para tirarme el pelo. —Lanzó un tierno suspiro, porque quería mucho al niño.

—¿En un tren por las Ghats? —dijo Punch, mientras se paraba en la cama—. ¿Hasta llegar a Nasik, donde vive la Rani Tigre?

—Este año no vas a ir a Nasik, pequeño sahib —dijo Meeta, mientras se lo subía al hombro—. Viajarás hasta la costa del mar, donde los cocos se caen, y cruzarás el mar en un barco muy grande. ¿Vas a llevar a Meeta con vos a Belait?

—Todos van a venir —dijo Punch, desde los fuertes brazos de Meeta—. Meeta y el aya y el hamal y el jardinero Bhini, y el salaam capitán sahib, el domador de serpientes.

No había burla en la voz de Meeta cuando respondió «Grande es el favor del sahib», y acostó al pequeño en la cama mientras el aya, sentada a la luz de la luna en el umbral de la puerta, lo arrulló con un cántico interminable, como los que cantan en la Iglesia Católica Romana de Parel. Punch se hizo un ovillo y se durmió.

A la mañana siguiente, Judy anunció a los gritos que había una rata en la habitación, y así fue como Punch se olvidó de contarle las excelentes noticias. No tenía mucha importancia, porque Judy solo tenía tres años y tampoco lo habría entendido. Pero Punch tenía cinco y sabía que ir a Inglaterra sería mucho más lindo que viajar a Nasik.

Papá y mamá vendieron el brougham y el piano, desmantelaron la casa, redujeron la cantidad de vajilla para usarla en las comidas diarias y deliberaron largo y tendido sobre un montón de cartas que llevaban el matasellos de Rocklington.

—Lo peor de todo es que uno no puede estar seguro de nada —dijo papá, retorciéndose el bigote—. Las cartas son excelentes y las condiciones bastante razonables.

«Lo peor de todo es que los niños crecerán lejos de mí», pensó mamá; pero no lo dijo en voz alta.

—No somos más que un caso entre cientos —dijo papá con amargura—. Volverás a casa dentro de cinco años, querida.

—Para entonces Punch tendrá diez años… y Judy ocho. ¡Qué largos, largos, larguísimos serán esos años! Y tendremos que dejarlos con extraños.

—Punch en un niño muy alegre. Estoy seguro de que hará amigos dondequiera que vaya.

—¿Y quién no querría a mi Ju?

Estaban de pie junto a las dos camitas en el cuarto de los niños, tarde en la noche, y creo que mamá lloraba en silencio. Cuando papá se marchó, mamá se arrodilló junto a la cuna de Judy. El aya la vio y rezó para que a la memsahib nunca le arrebataran el amor de sus hijos y se lo entregaran a un extraño.

La oración de mamá era un tanto ilógica. En resumen, decía: «Que esas personas desconocidas amen a mis hijos y sean tan buenas con ellos como yo lo sería, pero que pueda conservar su amor y su confianza para siempre. Amén». Punch se rascó entre sueños, y Judy gimió un poquito. Al parecer, esa fue la única respuesta a la plegaria. Al día siguiente, todos bajaron al mar, y hubo una escena en el Apollo Bunder cuando Punch descubrió que Meeta no podía ir con ellos y Judy comprendió que debían dejar atrás al aya. Pero Punch encontró mil cosas fascinantes en las cuerdas, las poleas y las tuberías de vapor del gran barco de la P&O mucho antes de que Meeta y el aya se hubieran secado las lágrimas.

—Volvé, Punch-baba —dijo el aya.

—Volvé —dijo Meeta—, y convertite en un burra sahib.

—Sí —dijo Punch, mientras su padre lo tenía en brazos y lo levantaba para que se despidiera con la mano—. Sí, voy a volver y entonces voy a ser un burra sahib bahadur.

Cuando el primer día llegó a su fin, Punch pidió que lo dejaran en Inglaterra, convencido de que debían de estar muy cerca. Al día siguiente, una brisa ligera agitó el aire, y Punch se mareó mucho.

—Cuando vuelva a Bombay, —dijo Punch en cuanto se recuperó del mareo—, voy a viajar por tierra en un gharri. Este barco es muy malo.

El contramaestre sueco lo consoló, y Punch fue cambiando de opinión a medida que el barco avanzaba. Había tanto para ver, tocar y preguntar, que prácticamente se había olvidado del aya, de Meeta y del hamal, y apenas recordaba algunas palabras en indostaní, la que alguna vez había sido su segunda lengua.

El caso de Judy era mucho peor. El día anterior a que el barco de vapor llegara a Southampton, mamá le preguntó si no le gustaría volver a ver al aya. Los ojos azules de Judy observaron el inmenso mar que había devorado todo su pequeño pasado, y respondió:

—¿Aya? ¿Qué aya?

Mamá lloró por ella, y Punch se asombró. Fue entonces cuando escuchó por primera vez la apasionada súplica de mamá: «No dejes que Judy se olvide de mamá». Dado que Judy era pequeña, absurdamente pequeña, y que mamá, todas las noches durante las últimas cuatro semanas, había entrado al camarote para arrullarlos con una melodía misteriosa que él llamaba «Mi niño del alma», Punch no podía entender a qué se refería. Pero se esforzó por cumplir su deber, porque en cuanto mamá salió del camarote, le dijo a Judy:

—Ju, ¿te acuerdás de mamá?

—¡Caro que sí! —dijo Judy.

—Entonces siempre acuerdate de mamá, o si no, no te voy a dar los patitos de papel que me regaló el capitán sahib de pelo rojo.

Y Judy prometió que siempre se «acuerdaría» de mamá.

Muchas pero muchas veces, mamá le repetía a Punch la misma súplica, y papá decía lo mismo con una insistencia que asombraba al niño.

—Tenés que aprender a escribir enseguida, Punch —decía papá—, para que puedas enviarnos cartas a Bombay.

—Entraré en tu habitación —dijo Punch, y a papá se le hizo un nudo en la garganta.

Papá y mamá siempre andaban con un nudo en la garganta aquellos días. Si Punch retaba a Judy por no «acuerdarse», se les hacía un nudo en la garganta. Si Punch se tumbaba en el sofá de la pensión en Southampton y dibujaba su futuro en tonos púrpura y dorado, se les hacía un nudo en la garganta; y lo mismo pasaba si Judy acercaba los labios para darles un beso.

Durante varios días, los cuatro fueron unos vagabundos sobre la faz de la tierra: Punch no tenía a quién darle órdenes, Judy era demasiado joven para todo, y papá y mamá estaban serios, distraídos y tenían un nudo en la garganta.

—¿Dónde está? —exigió Punch, harto ya de aquel horrible artefacto de cuatro ruedas que llevaba un montón de valijas encima—. ¿Dónde está nuestro gharri? Esto habla tanto que yo no puedo hablar. ¿Dónde está nuestro gharri? Cuando estaba en Bandstand, antes que nos viniéramos, le pregunté al sahib Inverarity por qué estaba sentado en nuestro gharri, y él me dijo que era suyo. Y yo le dije: «Te lo regalo» —me cae bien el sahib Inverarity—y le dije: «¿Podés meter las piernas por las correas de cuero a través de las ventanas?» Y el sahib Inverarity dijo que no, y se rió. Yo sí que puedo meter las piernas en las correas de cuero. Puedo meter las piernas en estas correas de cuero. ¡Mirá! ¡Uy! ¡Mamá está llorando otra vez! No sabía. No sabía que eso no se hace.

Punch sacó las piernas de las correas de cuero del carruaje de cuatro ruedas: la puerta se abrió y el niño se deslizó hacia el suelo, entre una catarata de paquetes, hasta la puerta de una austera casita de campo, con un cartel en la reja que rezaba «Downe Lodge». Punch se recompuso como pudo y miró la casa con desagrado. Estaba sobre un camino de tierra, y un viento frío le hacía cosquillas en las piernas cubiertas por pantalones bombachos.

—Volvamos —dijo Punch—. Este lugar es feo.

Pero papá y mamá y Judy ya se habían bajado del coche, y los criados estaban entrando todo el equipaje a la casa. En el umbral había una mujer vestida de negro, que sonreía ampliamente con los labios secos y agrietados. Detrás de ella había un hombre, grande, huesudo, canoso y rengo de una pierna, y detrás de él, un niño de doce años, de pelo negro y aspecto grasoso. Punch examinó al trío y se acercó sin miedo, como solía hacer en Bombay cuando alguien visitaba la casa y él estaba jugando en la galería.

—¿Cómo están? —dijo—. Mi nombre es Punch.

Pero todos miraban el equipaje, todos menos el hombre canoso, que le estrechó la mano y le dijo que era “un niño muy avispado”. Había mucho ajetreo y golpes de cajas por todos lados, y Punch se acurrucó en el sofá del comedor y se puso a reflexionar sobre la situación.

—Esta gente no me gusta —dijo Punch—. Pero no importa. Nos vamos a ir enseguida. Siempre nos vamos enseguida de todas partes. Ojalá ya estuviéramos de vuelta en Bombay.

Sus deseos no dieron fruto. Durante seis días, mamá lloró de forma intermitente y le mostró a la mujer de negro toda la ropa de Punch, un atrevimiento que a Punch no le gustó en lo más mínimo. «Aunque a lo mejor es una nueva aya blanca», pensó.

—Tengo que llamarla Tíarosa, pero ella no me dice sahib. Solo me dice Punch —le confió a Judy—. ¿Qué significa Tíarosa?

Judy no lo sabía. Ni ella ni Punch habían oído hablar de un animal que se llamara así. Su mundo se limitaba a papá y mamá, que sabían todo, permitían todo y querían a todo el mundo…incluso a Punch cuando iba al jardín en Bombay y se ensuciaba las uñas de tierra justo después del corte semanal porque, tal como le explicaba a su exhausto padre entre dos zapatillazos, “sentía las puntas de los dedos demasiado nuevas”.

Si bien no sabría decir por qué, a Punch le pareció mejor que sus padres estuvieran entre él y la mujer de negro y el niño de pelo negro. No le caían bien. Le agradaba el hombre canoso, que había expresado su deseo de que lo llamara «Tíoharri». Se saludaban con la cabeza cada vez que se cruzaban, y el hombre canoso le mostró un barquito con jarcias que subían y bajaban.

—Es una maqueta del Brisk; del pequeño Brisk que quedó tan expuesto aquel día en Navarino. —El hombre canoso murmuró esas últimas palabras y cayó en una ensoñación—. Ya te contaré la historia de Navarino, Punch, cuando salgamos a pasear; pero no toques el barco, porque es el Brisk.

Mucho antes de ese paseo, el primero de muchos, despertaron a Punch y Judy una fría madrugada del mes de febrero para decir adiós, entre todas las personas del planeta, a nada menos que a papá y mamá; esta vez los dos lloraban. Punch tenía mucho sueño y Judy estaba de mal humor.

—No se olviden de nosotros —les suplicó mamá—. Hijito mío, no te olvides de nosotros, y no dejes que Judy se olvide.

—Ya le dije a Judy que se acuerdara —dijo Punch, retorciéndose, porque la barba de su padre le hacía cosquillas en el cuello—. Le dije a Judy, diez, cuarenta, quichicientas veces. Pero Ju es muy chiquita; es casi una bebé, ¿no?

—Sí —dijo papá—, es casi una bebé, y vos tenés que ser bueno con ella, y hacer que aprenda a escribir y…y…

Punch volvió a su cama. Judy dormía profundamente, y abajo se escuchaba el traqueteo de un coche. Papá y mamá se habían marchado. No a Nasik; eso quedaba del otro lado del mar. A algún lugar mucho más cercano, por supuesto, y también, por supuesto, volverían. Volverían después de una fiesta, y papá volvería después de ir a un sitio llamado «Las Nieves», y mamá volvería con él, volverían con Punch y con Judy a casa de la señora Inverarity en Marine Lines. Seguro que volvían. Por eso Punch se volvió a dormir hasta bien entrada la mañana, cuando el niño de pelo negro lo recibió con la noticia de que papá y mamá se habían ido a Bombay, y Judy y Punch se quedarían en Downe Lodge «para siempre». Cuando, entre lágrimas, le pidió a Tíarosa que desmintiera las palabras del niño, ella se limitó a decir que Harry había dicho la verdad y que Punch tenía que doblar bien su ropa ante de irse a dormir. Punch salió y lloró con amargura junto a Judy, en cuya cabecita rubia había logrado inculcar cierta idea sobre lo que significaba la separación.

Cuando un hombre maduro descubre que ha sido abandonado por la Providencia, privado de su Dios y arrojado, sin ayuda, consuelo ni empatía a un mundo que le resulta nuevo y extraño, su desesperación —que puede reflejarse en una vida disoluta, en la escritura de sus experiencias o en la más satisfactoria distracción del suicidio— suele considerarse como algo impresionante. Un niño, en idénticas circunstancias, según lo que llega a entender, no puede insultar a Dios y morir. Llora hasta que se le enrojece la nariz, le arden los ojos y le duele la cabeza. Punch y Judy, sin tener ningún tipo de culpa, habían perdido su mundo entero. Se sentaron a llorar en el vestíbulo; el niño de pelo negro los miraba desde lejos.

La maqueta del barco no sirvió de nada, aunque el hombre canoso le asegurara a Punch que podía subir y bajar las jarcias tanto como quisiera; y a Judy se le prometiera libre acceso a la cocina. Ellos querían a papá y mamá, que se habían ido a Bombay, más allá del mar, y la pena que sentían no tuvo consuelo mientras duró.

Cuando las lágrimas cesaron, la casa se sumió en un silencio profundo. Tíarosa había decidido que lo mejor era dejar que «se desahogaran», y el niño se había ido a la escuela. Punch levantó la cabeza del suelo y soltó un respiro con tristeza. Judy estaba casi dormida. Sus tres cortos años aún no le habían enseñado a soportar el dolor con plena conciencia. Se oía un estruendo sordo y lejano… un golpe pesado que se repetía. Punch sabía que había escuchado ese sonido en Bombay, en la temporada del monzón. Era el mar… el mar que había que atravesar antes de poder llegar a Bombay.

—¡Vamos, Ju! —le gritó—. Estamos cerca del mar. ¡Puedo oírlo! ¡Escuchá! Ahí es adonde se fueron. A lo mejor los alcanzamos si llegamos a tiempo. No querían irse sin nosotros. Solo se olvidaron.

—Sí —dijo Judy—. Solo se olviraron. Vamo’ al mar.

La puerta del vestíbulo estaba abierta y también la del jardín.

—Es muy, muy grande este lugar —dijo Punch, mientras miraba el camino con recelo—. Nos vamos a perder, pero encontraré a un hombre y le diré que me lleve de vuelta a mi casa, como hacía en Bombay.

Tomó a Judy de la mano, y los dos huyeron sin sombrero en dirección al sonido del mar. Downe Lodge era casi la última de una fila de casas recién construidas que se extendían, entre un caos de ladrillos, hacia un páramo donde a veces acampaban los gitanos y donde practicaba la guarnición de artillería de Rocklington. No se veía mucha gente, y es probable que confundieran a los niños con los hijos de los soldados, que solían recorrer grandes distancias. Durante media hora, las piernitas agotadas caminaron por el páramo, el campo de papas y las dunas de arena.

—’Toy muy tansada —dijo Judy—, y mamá se va nojá.

—Mamá munca se enoja. Supongo que ahora está esperándonos en el mar mientras papá compra los boletos. Los vamos a encontrar y nos iremos con ellos. Ju, no te sientes. Un poco más y llegamos al mar. Ju, ¡si te sentás, te pego! —dijo Punch.

Subieron otra duna y llegaron hasta el extenso mar gris, con la marea baja. Cientos de cangrejos correteaban por la playa, pero no había ni rastro de papá y mamá, tampoco de un barco en el agua…no había nada más que arena y barro a lo largo de kilómetros y kilómetros.

Y Tíoharri los encontró de casualidad, muy embarrados y muy desamparados; Punch se deshacía en llanto, pero intentaba entretener a Judy con un «grangrecito» y Judy gritaba «¡Mamá! ¡Mamá!» mientras lloraba y miraba hacia el horizonte implacable… «¡Mamá!»

Natasha Besoky nació en Neuquén, Argentina, en 1994. Es traductora pública en idioma inglés (UNCo) y especialista en traducción literaria (UBA). Se desempeña como traductora independiente en distintas agencias de traducción y como docente de nivel superior de traducción literaria. Algunas de sus traducciones figuran en la página de Argentina Key Titles, un proyecto que busca promover la publicación de libros argentinos en otros idiomas, y en Barbárika, revista colombiana de literatura traducida.